Volume 4 Issue 1 (2006) DOI:10.1349/PS1.1537-0852.A.310 Note: Linguistic Discovery uses Unicode characters to represent phonetic symbols. Please see Optimizing Display for requirements to accurately reproduce this page. Saying Goodbye in the FieldLinguistic Society of AmericaAlbuquerque, NM • 7 January 20061. Introduction“Getting started” in the field is a frequently addressed topic in linguistic fieldwork manuals, field methods courses, and linguists’ reflections on their field experiences. Issues like finding informants and establishing the terms of work are widely acknowledged to be important elements of good fieldwork planning. But linguists have only recently begun to take seriously the long-term trajectories of the relationships they enter into in carrying out their research, and “saying goodbye” in the field has received virtually no attention at all. When fieldwork involves western linguists working in small endangered language communities, the linguist’s departure will often mean a withdrawal of resources and recognition by a powerful outside other. The moment of leave-taking may thus represent a significant transition in the field community’s relationship to wealth, power, and modernity, and its tone may have an enduring impact on a community’s self-perception, working either with or against the forces impelling language shift. The words and images that follow illustrate my departure from the Papua New Guinea (PNG) village where I lived for fifteen months documenting the endangered Cemaun dialect of Arapesh. As I will show, the villagers welcomed me not only because they cared about the diminishing vitality of their language, but also because my interest affirmed for them the virtue of their community and its relevance in the wider world. In Melanesia it is customary to honor guests with a feast when they take leave, in an effort to ensure that material exchange (and hence social engagement) with those left behind will one day be renewed despite the distance and passage of time. The feast made upon my departure was extraordinary in the forms of exchange it occasioned and its positive reflection on the villagers’ social identity. It also presented an opportunity for new and creative uses of Cemaun. From a western perspective, the event marked a step in the documentation of an endangered language, the successful completion of an important project. But for the villagers, the event also marked the end of a period in which the care and concern of a powerful outsider was directed specifically toward their community, indexing its value. Once my work was finished, the villagers wondered, would there still be some basis for our relationship? And I wondered whether there was any way to wind up my fieldwork and leave in this cultural context without reinforcing the community’s sense of marginality, precisely what the villagers were seeking to symbolically overcome by shifting their linguistic allegiance away from the vernacular, and onto Tok Pisin. 2. “Giving back” to the community is good, but we must also know how to receiveConcerned as we are with giving back to our research communities, it is easy to neglect the question of how to take in culturally appropriate ways. In Melanesian societies, social relationships are carried out through the medium of exchange. People are constantly giving and receiving gifts of material objects, especially food. Those who have more are expected to give more. My husband and I had a houseful of desirable possessions—cooking pots, buckets, blankets, etc.—and we were now ready to give them away. But how to do this without swamping the people’s own generosity? Early the morning before our departure, we divided our belongings into piles, one for each hearth in the village. Big items such as my mattress, chair, and stove were designated for those with whom I’d worked most closely.

We publicly called up a woman from each household and gave her her family’s pile, just as food gifts are formally distributed at feasts. We did this early in the day, so that their goodbye gifts to us would be transacted afterwards. Why? If guests are indebted to their hosts when they leave, they can be expected to one day return and reciprocate. Such an imbalance is felt to be good, since it provides grounds for a continued relationship.

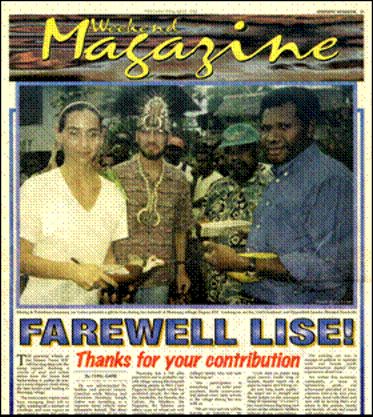

3. Good exchange relations make good public relationsMembers of the village diaspora, successful professionals and prominent politicians living in the national capital, returned home for the goodbye feast. I was showered with valuable gifts. Because our strong exchange relationships reflected on the village so positively, a newspaper reporter was flown in to publicize the event. Front page stories later appeared in the weekly magazine inserts of the country’s two English language dailies.

While the articles mention my linguistic research, their focus is on aspects of my exchange relationships with the villagers:

4. Our focus may be on the language, but theirs is on their communityPeople gathered in the village meeting house for farewell speeches. In the keynote speech given by Bernard Narokobi, a founding father of the nation, former speaker of parliament, and respected village leader, the central theme was my work’s reflection on the worthiness of the community:

5. Harnessing the power of traditional motivations to help reinvent the vernacularIt is widely accepted that vernacular language educational and religious materials can be positive resources that strengthen local languages. But we should also recognize the power of occasions—such as leavetaking—to provide contexts for using local languages in ways that evoke the motivations and values of the cultures themselves. The farewell feast held at my fieldwork’s conclusion provided an occasion for new uses of the vernacular that were energized by the significance that relationships with outsiders have in the culture.

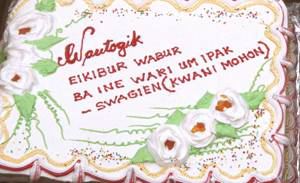

Among my contributions to the feast was this cake. It was decorated with writing in Cemaun, and signed with my Arapesh name, Swagien: Wautogik My village I will miss you — Swagien (and your in-law) Cemaun is used but rarely now. Older villagers address it only to one another; children often do not understand the most common commands and greetings. But in this context the language was appropriately addressed to the entire community. Arapesh ulaihəs ‘song/dance complexes’ (sg. ulai) are as much a political as an artistic genre, concerned with a community’s self-presentation. To honor my departure, the community chose the Mawɔn ulai, one of the few ulaihəs that is sung in Arapesh, albeit in a dialect other than Cemaun. Its tone is mournful, and its verses terse and allusive. For example, one verse laments a man’s departure from Arapesh lands to work in the goldfields: “The pouring rain will carry me away…. I’m going alone to Wau.” New verses of Mawɔn were composed especially for my departure:

My departure provided the first occasion in years for the villagers to sing and dance Mawɔn. The event went on from dusk to dawn.

6. What this means for linguistic fieldworkIn thinking about what we can give back to our field communities we naturally tend to focus on the standard products of our work: dictionaries, grammars, pedagogical materials, etc. But we must keep in mind that the relationships we form are themselves important products of our work. Such relationships are a valuable means through which we can support local languages.

Departing from the field brings the relationship between fieldworker and community into focus, always in a culturally specific way that evokes people’s own ideas about their identity in relation to cultural others. Arapesh is an “importing” culture, one which values the ability to “pull things in” from outside. This cultural orientation is reflected not only in the community’s relationship to me, an outside researcher, but also in their eager appropriation of Tok Pisin, an outside language. When I said goodbye in the field, it brought up some of the most important issues facing the community I worked with as it negotiated its identity in a changing world. At this sensitive time I tried my best to respond to the community’s concern to construct a positive relationship with me as a cultural other, recognizing that this same set of concerns was implicated in the language’s endangerment. |

[ Home | Current Issue | Browse the Archive | Search the Site | Submission Information | Register for Updates | About | Editorial Board | Site Map | Help ]

Published by the Dartmouth College Library.

|