Volume 4 Issue 1 (2006) DOI:10.1349/PS1.1537-0852.A.304 Note: Linguistic Discovery uses Unicode characters to represent phonetic symbols. Please see Optimizing Display for requirements to accurately reproduce this page. Na(t)ive Orthographies and language endangermentTwo case studies from Siberia(from the poster presented at LSA 2005)1 IntroductionIn this poster, we present findings on the invention and use of naïve (native) orthographies among two vanishing minority groups of central Siberia, the Ös (also called Middle Chulym) and the Tofa. Despite small numbers of speakers, both of these moribund languages have recently acquired native literary and orthographic traditions: one introduced from above, by linguists, and another invented by a member of the speech community. We documented patterns of use and adaptation of these two systems, as well as attitudes expressed by towards them by individuals. Specific developments in the conventional use of graphemes shed light on the psychological reality of phonemes and phonological and prosodic processes. Attitudes towards new writing systems as well as their uses help to elucidate the politics of literacy. 1.1 History and demographyUnlike the vast majority of indigenous minority languages of the former Soviet Union, neither Tofa [kim] nor Ös [clw] were ever officially committed to writing in a state-sanctioned bilingual program. Instead they suffered, to varying degrees, the consequences of open hostility from the state. Despite adverse conditions, both communities have shown a nascent indigenous literary tradition and native attempts to codify the once active oral literary tradition before it is lost altogether.

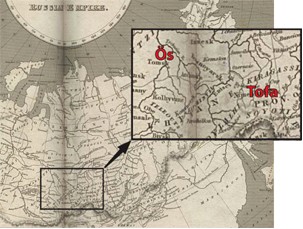

Figure 1a: Historical map with locations of Ös and Tofa indicated. Map from The Cyclopaedia or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature by Abraham Rees, 1820, Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, University of Texas at Austin

Figure 1b: Modern schematic map for comparison. 2 TofaThe Tofa live in three remote villages in east-central Siberia, Irkutsk region. They are subsistence hunter-gatherers and reindeer herders in the eastern Sayan mountains of Siberia. Although the Tofa number around 600 persons, only 35 still speak the Tofa language.

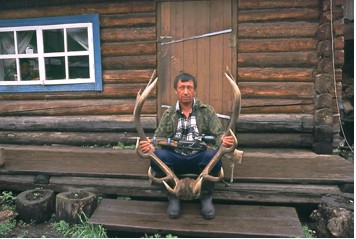

Figures 2 and 3: Tofa consultants Marta Kongaraeva (above) and her son (below) Sergei Kangaraev.

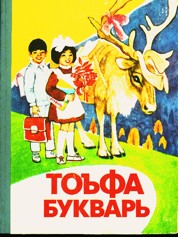

2.1 Official orthographyWhile the Tofa never received an orthography from the Soviet state, they were presented one in 1989 from a linguist, V. I. Rassadin, who married a member of the community but lived permanently outside it. It was based on Cyrillic and included a total of nine new letters lacking in the Russian form of the script.

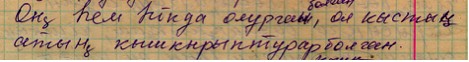

Figure 4: ABC book with ‘official’ Tofa orthography Created with virtually no native input, the script was also linguistically unsound, encoding many sub-phonemic distinctions. 2.2 “Too many letters”Although there were 3 storybooks (e.g., Rassadin and Shibkeev 1989) and a Russian-Tofa dictionary (Rassadin 1995) published with the script, it never gained many users; the community rejected it as too complex and cumbersome. Speakers complained that it had “too many letters.” In our 2001 survey of the Tofa-speaking community, we found this orthography actively used by only a single person, a semi-speaker who was charged with conducting basic vocabulary lessons for local schoolchildren. 2.3 Native modified writingHowever, for the last decade or so, accomplished Tofa storytellers and others literate in Russian have attempted a variety of independent, though not necessarily systematic, ‘naïve’ orthographic to simplify and rationalize Tofa letters, adopting new conventions that make sense for Tofa.

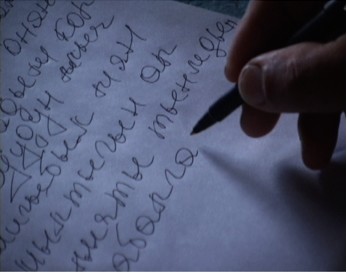

Figure 5: “He sat down by the riverbank and began calling out that girl’s name.” (Svetlana Araktaeva, 2002) 2.4 Phonological decisionsOne such system, that of Svetlana Araktaeva, is shown in figure 5. In this sample, contrastive vowel length is ignored, front vowels are rendered as palatal consonant + vowel, and the Russian ‘hard’ sign <Ъ>, which has no meaning for Tofa, is re-utilized to indicate low pitch on a preceding vowel. Vowel harmony, though highly variable, is shown in writing. 2.5 MorphosyntaxAraktaeva’s writing also sheds light on perception of word boundaries and the structure of serial verbs. In the writing sample shown here, she conflates three serial verbs into a single written word, indicating perhaps an ongoing process of univerbation.

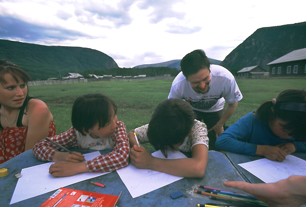

Figure 6: Photograph of Tofa children illustrating “Tofa Tales.”

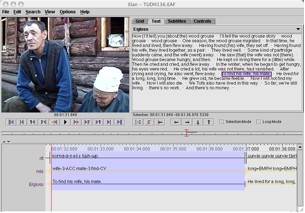

Figure 7: An annotated screen shot of Konstantin Mukhaev telling a Tofa story. 3. ÖsThe Ös people of Central Siberia, also called ‘Middle Chulym’, are traditional hunter-gatherers & fishermen living in the Tomsk region of central Siberia. The Ös tribe has 726 members, but the language is spoken by fewer than 40 people scattered across seven villages.

Figure 8: Ös consultant Vasillij Gabov describes how he invented his own writing system. There has never been an attempt to devise an orthography for Ös, in part due to the open hostility directed toward the people from the Russian state: writing is Ös was forbidden and the language repressed. For a variety of socio-political reasons, the Ös were dropped from the census as a separate ethnic group in 1959, and incorrectly lumped together with other ethnic groups. Official re-recognition happened only in 1998, and the Ös have seen few tangible results. 3.1 Ös writing invented, then abandonedDespite the lack of an official orthography for Ös, one member of the community, Vasillij Gabov, devised a remarkably ingenious Russian-based orthography to render this phonetically quite different language. In 2003, Gabov told us how he had discarded his book and abandoned writing after being ridiculed by a Russian member of the community (1-26).

Figure 9: Screenshot of Gabov’s hand writing Ös V. Gabov Narrating His Invention of Writing

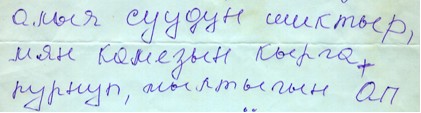

3.2 Phonological decisionsFigure 10 shows an example of Gabov’s orthography. No new symbols were introduced to the Russian Cyrillic, but script was made to fit Ös. Gabov modified the orthography using novel combinations. For instance, the Russian ‘soft sign’ <Ь> can be used after the first non-initial consonant to indicate that all vowels in the word are front. This solution implicitly recognizes vowel harmony operating across entire word-domains.

Figure 10: “The moose emerged from the water, I brought my boat to shore, grabbed my gun, and...” (Gabov, 2003) 3.3 Linguists’ ContributionsThe authors worked with this speaker to revive his orthography and produce a Middle Chulym storybook. Preliminary studies show this orthography to be easily accessible to other members of the community. The first Ös book ever published to appear in 2005. It uses Gabov’s orthography and features stories and illustrations by community members. We field tested it in 2005 and it got positive reactions from community members, several of whom were able to read it aloud. We estimate the potential readership is 20-25 persons, but as an item of linguistic prestige, we expect it will have wider impact.

Figure 11: Ös children illustrate the storybook: frame from forthcoming film The Last Speakers

Figure 12: Page of Ös children’s book Referencesvarious (2006 forthcoming) Ös chomaktary: Middle Chulym Tales. Prepared and translated by Gregory D. S. Anderson and K. David Harrison, with stories by V. Gabov and I. Skoblin. Eugene, OR: Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages. Kramer, Seth and Daniel Miller, producers (2006). The Last Speakers. New York, NY: Ironbound Films. Rassadin, V. I. and V. N. Shibkeev. 1989. Tofa bukvar. Irkutsk: VSKO. Rassadin, V. I. 1995. Tofalarsko-russkij russko-tofalarskij slovar’. Irkutsk: VSKO. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[ Home | Current Issue | Browse the Archive | Search the Site | Submission Information | Register for Updates | About | Editorial Board | Site Map | Help ]

Published by the Dartmouth College Library.

|