Volume 2 Issue 1 (2003) DOI:10.1349/PS1.1537-0852.A.142 Note: Linguistic Discovery uses Unicode characters to represent phonetic symbols. Please see Optimizing Display for requirements to accurately reproduce this page. A Particle of Indefiniteness in American Sign Language[*]We describe here the characteristics of a very frequently-occurring ASL indefinite focus particle, which has not previously been recognized as such. We show that, despite its similarity to the question sign “WHAT”, the particle is distinct from that sign in terms of articulation, function, and distribution. The particle serves to express “uncertainty” in various ways, which can be formalized semantically in terms of a domain-widening effect of the same sort as that proposed for English ‘any’ by Kadmon & Landman (1993). Its function is to widen the domain of possibilities under consideration from the typical to include the non-typical as well, along a dimension appropriate in the context. 1. IntroductionIn this article, we describe a focus particle that occurs with great frequency in American Sign Language (ASL) in indefinite contexts. This particle has not been previously identified as such in the ASL literature. Although its articulation is similar to that of the generic question sign conventionally glossed as “WHAT”, the two signs are distinguishable in terms of articulation, function, and distribution. Here we discuss the characteristics of this particle and the kinds of contexts in which it occurs. It serves to express “uncertainty” in a variety of ways. In the final section, we address the semantics associated with this particle and propose that it has a domain-widening effect comparable to that proposed by Kadmon and Landman (1993) for any in English. This ASL particle functions to widen the domain of possibilities under consideration along some contextually determined dimension. 2. Background about American Sign LanguageDespite the difference in modality, signed languages have the same fundamental organization as spoken languages. Neidle et al. (2000) have argued that the basic hierarchical structure of American Sign Language (ASL) is as illustrated in Figure 1, and thus is completely comparable to what has been proposed for spoken languages.

2.1. Nonmanual Correlates of Syntactic FeaturesOne particularly interesting characteristic of signed languages is the use of nonmanual expressions (gestures of the face and movements of the head and upper body), which extend over phrasal domains, to express grammatical information. This is one important use (of many) for nonmanual expressions in signed languages. Neidle et al. (2000:43-45) have proposed the following generalizations for the distribution of nonmanual syntactic markings:

2.2. Question ConstructionsQuestion constructions have been the subject of some controversy in the literature, with respect to both the facts and analysis.[1] Neidle et al. (2000:chapter 2) discuss possible contributing factors to the conflicting reports in the literature, some related to methodological problems in eliciting grammaticality judgments from native signers. The fact that most of the constructions reported in the literature on ASL syntax are given only in gloss form (using the nearest equivalent English translation for each ASL sign) makes it difficult to evaluate claims and conclusions about ASL data. To avoid this problem, the American Sign Language Linguistic Research Project (ASLLRP) has made available digital video examples, signed by native signers of ASL, illustrating the constructions we discuss in this paper and others. These can be obtained on CD-ROM and at our Web site <http://www.bu.edu/asllrp/>.[2] For simplicity of exposition here, we will focus on those sentences that have a single wh-phrase.[3] The wh-phrase (e.g., WHO, WHERE, WHEN, etc.) may surface either in situ or at the right periphery of the clause. There is a distinction between the two positions in terms of interpretation: when the wh-phrase is at the right periphery, it is necessarily interpreted as focused.[4] The distribution of the nonmanual marking characteristic of wh-questions (labeled as ‘whq’ and consisting of a cluster of properties, including furrowed brows, squinted eyes, and a slight side-to-side headshake)[5] also differs.[6] If the wh-phrase is in situ, the wh-marking obligatorily spreads over the entire CP. In contrast, when the wh-phrase occurs at the right periphery, spread of the marking over the rest of the CP is not required. This provides the basis for an argument (Neidle et al., 2000) that the final wh-phrase is in a right-peripheral Spec, CP: the wh-phrase provides manual material local to the +wh feature of C, so spread of the nonmanual +wh marking over the c-command domain of C is not obligatory. Wh-constructions are illustrated in (1)–(8). Glossing conventions for representing ASL sentences are explained in the Appendix. For further details about conventions used for annotation, see Neidle (2002). Wh-phrases in situ

Hyperlinks: Example 1

Hyperlinks: Example 3

Wh-phrases at the right periphery

Hyperlinks: Example 5

Hyperlinks: Example 6

Hyperlinks: Example 7

Hyperlinks: Example 8

There is something interesting about (7) as signed in the video illustrating this sentence (in particular, with respect to the non-dominant hand); this is not annotated here and we will return to discuss it in section 3.5. Wh-signsOne of the common wh-signs is conventionally glossed as “WHAT”. This sign involves a side-to-side shaking of the hands in front of the chest, with a 5 handshape (all five fingers extended), palms facing upward, as in the following sentences:

Hyperlinks: Example 9

Hyperlinks: Example 10

The sign glossed as “WHAT” can also occur in a sentence-final tag with a construction that contains a different wh-sign, as shown in (11).[7]

Hyperlinks: Example 11

3. Discovery of a Previously Unidentified ParticleThe construction illustrated in (12) and (13) involves a sign, glossed here as ‘part:indef,’ that is similar to the final sign in (9)–(11), but critically different from it.

Hyperlinks: Example 12

Hyperlinks: Example 13

In this construction, the final sign is articulated with the same handshape as “WHAT” (i.e., a 5 handshape, palms facing upward), but it involves a single outward movement, rather than side-to-side shaking of the hands. In the corresponding video examples, the particle is signed with one hand (the dominant hand) in (12), but with both hands in (13), as indicated by the notation ‘(2h).’ Here this is due to the preceding sign being one-handed (YESTERDAY) or two-handed (CAR). However, there are many variations that are possible as to whether this particle is signed with the dominant hand, the non-dominant hand, or both (potentially held over differing domains). Given the similarity of the articulation, and the fact that this particle occurs frequently in wh-questions, it is understandable why it might have been confused with the sign “WHAT” by researchers (including ourselves) in the past. However, this indefinite particle (unlike the wh-sign “WHAT”) can occur in non-wh contexts. 3.1. Distribution: Occurrence in Non-wh ConstructionsThe particle just described can occur in a wide variety of contexts, the unifying characteristic of these contexts being some degree of uncertainty. Along with wh-constructions of the type shown in (12) this particle can occur in yes-no questions involving some kind of indefiniteness, whereas the wh-sign “WHAT” would be ungrammatical in yes-no questions.

Hyperlinks: Example 14

Hyperlinks: Example 15

The sign glossed as ‘SOMETHING/ONE’ can be used to mean either ‘something’ or ‘someone’. The meaning conveyed by the particle is not reflected in the English translation of these sentences, as there is no natural way in English to convey this. The semantics associated with this particle will be discussed in section 4. For now, we will simply observe that this particle occurs with great frequency in yes-no questions. Note that it would not be acceptable to replace the particle in (14) and (15) with “WHAT”. This particle also occurs frequently in negative constructions, as illustrated in (16) and (17).

Hyperlinks: Example 16

Hyperlinks: Example 17

Again, replacing the indefinite particle with the sign “WHAT” in these sentences would result in ungrammaticality. The indefinite determiner SOMETHING/ONE used in the yes-no question in (14) is also sufficient to license the indefinite particle even in affirmative sentences. When the particle occurs with the indefinite determiner/pronoun, it may appear in any of several positions (and sometimes in more than one position), as illustrated in (18)–(26). The interpretation differs a bit depending on where the particle occurs (as we have attempted to show with the English translations, although, as mentioned earlier, these translations do not completely reflect the meanings). The particle in (19) is initially signed with two hands, after which the non-dominant hand retains the position of the particle throughout the articulation of the sign SOMETHING/ONE on the dominant hand; the non-dominant hand then participates in the articulation of the two-handed sign BOAT that follows.

Hyperlinks: Example 18

Hyperlinks: Example 19

Hyperlinks: Example 20

Hyperlinks: Example 21

Hyperlinks: Example 22

Hyperlinks: Example 23

Hyperlinks: Example 24

Hyperlinks: Example 25

Hyperlinks: Example 26

The English translations given above represent the situation where SOMETHING/ONE refers to an inanimate entity (although, as previously mentioned, it can also be used with the meaning of ‘someone’). As we see, when the particle is used sentence-finally, it often indicates uncertainty about the proposition as a whole, whereas when it modifies a determiner or pronoun internal to the clause, it indicates uncertainty with respect to the noun phrase with which it is associated. This particle also frequently occurs in other constructions that involve uncertainty, such as sentences that contain non-factive verbs such as ‘guess’ and ‘think’ as in (27) and (28), or adverbials such as MAYBE, as in (29).[8]

Hyperlinks: Example 27

Hyperlinks: Example 28

Hyperlinks: Example 29

It is also interesting to note in passing the similarity in articulation between the indefinite particle and the sign MAYBE. MAYBE is articulated with the same handshape as part:indef: the hands are extended, with a 5 handshape, palms facing upward; one hand is raised slightly as the other hand is lowered slightly, and then the hands reverse those motions. There are other signs with similar meaning and handshape; for example, the sign meaning ‘approximately’ is articulated with the same handshape, palm facing forward, and a slight circular movement. Two additional examples taken from stories by Mike Schlang illustrate the use of the particle with the verbs HOPE and WISH:

Hyperlinks: Example 30

Hyperlinks: Example 31

In summary, then, this particle can occur in sentences entailing some degree of uncertainty or tentativeness, whether this is expressed through verbs or adverbs. In addition, the particle may occur in situations where the uncertainty expressed relates to the discourse context, rather than to some specific element present in the sentence itself. In the literature, the particle occurring in such contexts has frequently been glossed as ‘WELL’. However, we believe that most (if not all) occurrences of the discourse particle WELL actually involve this same particle of indefiniteness.

Hyperlinks: Example 32

Hyperlinks: Example 33

The implicit uncertainty in (33) seems to be in regard to whether father will really do it. That is, it is significantly less than certain that father will give the car to John.[9] Although many occurrences of the particle traditionally glossed as ‘WELL’ can be understood as involving this particle of uncertainty, it is not clear whether all instances can be analyzed in this way. There also seems to be a kind of emphatic use of this discourse-level particle to mark a transition between topics. In the vast majority of these cases, some type of uncertainty may indeed be involved, but it is unclear how to succinctly characterize its distribution with respect to discourse structure. Many occurrences of this particle are found in excerpts of several stories distributed by DawnSignPress that we have annotated using SignStream. These annotations are available on CD-ROM, and we would invite readers to observe the use of this particle in the specific discourse context of stories, such as Freda Norman’s “Dead Dog” story. One example is provided here:

Hyperlinks: Example 34

Here the uncertainty presumably relates to how this could have happened. There is also another kind of discourse use of this particle, involving a stressed production of part:indef, separated from the rest of the sentence by a marked prosodic break, as illustrated in (35) and (36). In question contexts, this emphatic articulation of the particle conveys a stronger request for a reply than when the particle is articulated without stress. (The particle is, in this case, accompanied by certain other nonmanual markings associated with questions, such as wide eye aperture, raised or lowered eyebrows—depending on the type of question—and a forward lean of the body.) This particle (like its unstressed counterpart) can be used in yes-no questions, unlike the sign “WHAT”.

Hyperlinks: Example 35

Hyperlinks: Example 36

In summary, then, the particle under consideration is articulated in a way that is similar to, but distinguishable from, the wh-sign glossed as “WHAT”. The sign “WHAT” involves a side-to-side movement of the hands, while the indefinite particle involves a single outward movement. Whereas the sign “WHAT” is restricted to wh-contexts, the indefinite particle may appear in a variety of other contexts where there is indefiniteness or uncertainty with respect to an element in the sentence. Given that wh-questions themselves intrinsically involve an indefinite operator, this is an ideal environment for the indefinite particle to occur; however, the use of the indefinite particle is more general. Before returning, in sections 3.4 and 3.5, to consider other constructions in which this particle occurs, it will be useful to discuss, in more detail, the realization of this particle in ASL: both its manual expression and its nonmanual correlates. 3.2. ArticulationIn light of the frequency with which this particle occurs, it is rather striking that it has not been described and analyzed previously. The phonological reduction that frequently occurs may have been a contributing factor in its having been overlooked. There is a tendency for this particle to cliticize phonologically (or to contract) with the sign it follows. In such cases the handshape and location of the prior sign are maintained, with part:indef being realized by the addition of an outward movement of one or both hands (depending on whether it follows a one-handed or two-handed sign). Often, this kind of assimilation occurs after the wh-signs WHY, FOR-FOR (a variant meaning ‘why’ or ‘what for’), WHO, HOW, HOW-MANY, WHERE, WHICH, etc. In the examples below, the symbol ^ represents such contractions, e.g., WHY^part:indef.

Hyperlinks: Example 37

Hyperlinks: Example 38

Hyperlinks: Example 39

Hyperlinks: Example 40

In (37) through (39), the wh-signs are articulated solely with the non-dominant hand, which finishes off with an articulation of the indefinite particle; the articulation of the indefinite particle on the non-dominant hand begins at the same time as the wh-phrase (i.e., before the particle is signed on the dominant hand), and continues through the articulation of the particle on the dominant hand. In (40), however, since HOW is a 2-handed sign, both hands articulate the wh-sign followed by the particle. Sometimes, the movement associated with the indefinite particle is very subtle. For instance, there are cases where it is unclear whether or not the wh-sign (“WHAT”) is followed by this particle. Frequently the movement associated with the particle may be subtler on one hand than on the other. Sometimes, in fact, when the non-dominant hand has not been actively engaged in signing (but may, for example, be resting on the lap of a seated signer), there is nonetheless a small yet detectable outward turning of the palm on the non-dominant hand as the dominant hand produces this particle. In addition to its ability to cliticize, the particle is also capable of undergoing perseveration in an utterance. Perseveration (maintenance of a handshape that will be used again) is a fairly general phenomenon in ASL; for instance, it occurs frequently with classifiers. Manual perseveration of the non-dominant hand in the production of the sign “WHAT” was first noted by Neidle et al. (1994). It was observed that, in constructions involving two instances of “WHAT” (see note 3), the non-dominant hand may retain the handshape for “WHAT” between two occurrences of the sign. Sentence (41) illustrates this phenomenon.

Hyperlinks: Example 41

As in those cases involving “WHAT”, the particle may also exhibit perseveration by the non-dominant hand throughout part or all of the utterance, as shown in (42) and (43).

Hyperlinks: Example 42

Hyperlinks: Example 43

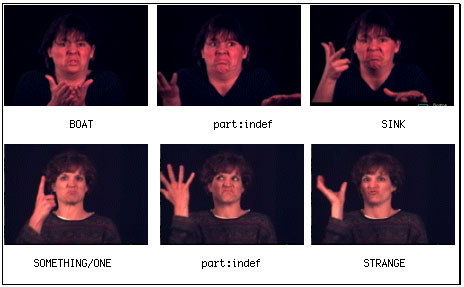

3.3. Nonmanual CorrelatesThere are nonmanual expressions that typically occur with expressions of uncertainty. As observed by MacLaughlin (1997, p. 119), nouns, verbs, and adjectives conveying some degree of uncertainty—including the sign SOMETHING/ONE, which functions as determiner or pronominal—are frequently associated with a tensed nose, lowered brows, and sometimes also raising of the shoulders. These same expressions frequently occur with the indefinite particle, although the eyebrows are sometimes raised (typical of focused constituents). We have also observed that this particle frequently occurs with a sudden shift in eye gaze to the left or right, as shown in Figure 2 with respect to sentences (24) and (21), discussed earlier and repeated here as (44) and (45).

Hyperlinks: Example 44

Hyperlinks: Example 45

This eye behavior remains to be studied carefully, but there is a definite pattern that has emerged from our data.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Lateral view (782K) |

Front view (838K) |

Close-up (1.1MB) |

Hyperlinks: Example 47

|

Lateral view (1.6MB) |

Front view (1.6MB) |

Close-up (2.2MB) |

Hyperlinks: Example 48

|

Lateral view (1MB) |

Front view (1.1MB) |

Close-up (1.4MB) |

As with the complements of non-factive verbs (recall (27)-(29)), these are situations in which the truth of the embedded proposition is called into question. It is interesting that in these examples the particle is signed solely on the non-dominant hand and may be held, at least until that hand is needed to participate in the articulation of a 2-handed sign, such as RAIN or PARTY.

Another similar use of the indefinite particle is illustrated in the following example, taken from a story by Mike Schlang:

Hyperlinks: Example 49

|

Front view (1.1MB) |

Close-up (732K) |

3.5. Wh-questions

As already noted, this particle occurs with great frequency in wh-questions, as illustrated here:

Hyperlinks: Example 50

|

Lateral view (1.2MB) |

Front view (1.3MB) |

Close-up (1.8MB) |

Hyperlinks: Example 51

|

Lateral view (822K) |

Front view (846K) |

Close-up (1.2MB) |

Hyperlinks: Example 52

|

Lateral view (771K) |

Front view (798K) |

Close-up (1.1MB) |

Hyperlinks: Example 53

|

Lateral view (937K) |

Front view (920K) |

Close-up (1.3MB) |

In some cases, the particle may be articulated on one hand while the wh-phrase

is articulated with the other, as occurred in sentence (8), repeated here

as (54):

Hyperlinks: Example 54

|

Lateral view (528K) |

Front view (497K) |

Close-up (648K) |

3.6. Summary Thus Far

We have identified a previously overlooked particle in ASL that occurs with great frequency in question constructions and sentences that involve some kind of indefiniteness. This particle occurs with a precise distribution and interacts phonologically with other signs, as discussed in section 3.2.[10]

4. Semantics of the Indefinite Focus Particle

In this section, we will attempt a more rigorous statement of the contribution of part:indef to the meaning of the utterance. We note at the outset, however, that our conclusions will necessarily be tentative, as the full range of contexts in which the part:indef particle can appear requires further systematic exploration.

Let us consider first the cases in which part:indef appears with indefinites. Here, the effect of part:indef seems to be to extend the domain of reference to beyond the typical, resulting in a “widening” reminiscent of that proposed by Kadmon and Landman (1993) for English any. That is, whereas (55) simply asserts that a boat sank near Cape Cod, (56) (repeating (18)) asserts that some (perhaps unusual) kind of boat sank near Cape Cod, and (57) (repeating (24)) asserts that some boat or perhaps something only relevantly like a typical boat sank near Cape Cod.

Hyperlinks: Examples 55

|

Lateral view (1.3MB) |

Front view (1.4MB) |

Close-up (1.9MB) |

Hyperlinks: Example 56

|

Lateral view (292K) |

Front view (208K) |

Close-up (281K) |

Hyperlinks: Example 57

|

Lateral view (951K) |

Front view (974K) |

Close-up (1.4MB) |

Adapting Kadmon and Landman’s (1993) condition on any we could characterize this as follows:

Thus, whatever the extension of the phrase would be without part:indef (normally fairly restricted contextually), it would be expanded to include other referents when part:indef is attached. The examples in (55)–(57) also demonstrate that part:indef has scopal properties; it can attach to different types of phrases and will widen the interpretation of whatever phrase it is attached to. In this connection, however, we should also point out part:indef appears to be allowed at or above its logical scope position (at least superficially like only in English); thus, many of the cases discussed below where part:indef appears higher in the structure also have alternative interpretations in which part:indef logically associates with an internal constituent.

The explanation of part:indef with indefinites given above can be extended straightforwardly to the cases of part:indef with wh-words. We take a wh-word, in a certain sense, to “stand in for” the possible phrases that could replace it in a well-formed answer (see, e.g., Hamblin (1973) and most subsequent work on questions). Usually, the range of values that a wh-word can stand in for is contextually restricted in much the same way as an indefinite like someone, and just as with the indefinites discussed above, when used with a wh-word part:indef also expands the domain of possible referents. This conveys the feeling that the questioner really has no idea what the answer is, that the true answer might be outside the set of possible answers the questioner would consider typical. [11]

Whereas part:indef appears to be subject to Widening, it does not appear to be subject to Kadmon and Landman’s (1993) Strengthening condition on English any. This is clear already from (56): the fact that some (perhaps unusual) kind of boat sank near Cape Cod does not further entail that a (usual) boat sank near Cape Cod. However, the Widening effect on part:indef does make it particularly well-suited for contexts in which negative polarity items like the English any appear, since it creates a stronger (more informative) statement. One example illustrating the semantic Widening effect (here on the main predicate) is given below, taken from a story by Mike Schlang, “Dorm Prank”. In (59), the particle extends the characterization of the hall monitor that is being negated: not only was the hall monitor not friendly, he was nothing like friendly.

Hyperlinks: Example 59

|

Front view (79.5MB) |

Close-up (56.1MB) |

Returning to the cases where the particle is associated semantically with a sub-sentential constituent, such as WHO or SOMETHING/ONE, it is noteworthy that the particle is used only when that constituent is in focus. Consider, for example, the cases where WHO is followed by a phonologically reduced version of the particle (expressed solely with the dominant hand). This does not naturally occur when the wh-phrase is in situ. Sentence (60) would be unnatural (without a great deal of stress on the first sign followed by a significant pause, marking that in situ phrase as being in focus).

In contrast, the sentences shown in (61) would occur quite naturally in a context where it was known that somebody saw Joan and the questioner wished to ask who saw Joan. Again, rightward wh-movement of WHO occurs only when it is focused.

Hyperlinks: Example 61a

|

Lateral view (995K) |

Front view (1MB) |

Close-up (1.4MB) |

Hyperlinks: Example 61b

|

Lateral view (944K) |

Front view (969K) |

Close-up (1.3MB) |

Moreover, part:indef is not allowed with just anything focused in the sentence. For use of part:indef, it must be the indefinite that is in focus. If the questioner wanted to know whether anyone saw Joan (that is, in a context like “I know that Bill didn’t see Joan, but),the questions in (62) are quite natural, but with focus on Joan (that is, in a context like “I know that nobody saw Bill, but), neither variant in (62) would be natural.

Hyperlinks: Example 62b

|

Lateral view (958K) |

Front view (986K) |

Close-up (1.3MB) |

As expected given the analysis so far, we find that in a negative context, such as (63)(=16)), the particle can play a role similar to English any. On one reading of (63), the particle serves to emphasize that mother should not buy any cars, typical or not.

Hyperlinks: Example 63

|

Lateral view (286K) |

Front view (265K) |

Close-up (266K) |

Another available reading of (63) comes about by Widening higher, at the VP level, where what is meant is that Mother should not buy a car or do anything like buying a car. In English, this kind of meaning can be expressed colloquially with “or something” or “or anything,” as in the following examples.

|

(64) |

Did you go to Europe? |

|

(65) |

Did you go to Europe or anything? |

|

I didn’t buy a book or anything. |

Sentence (64) is simply asking whether or not the proposition that you went to Europe is true, while (65) asks whether you went to Europe or did anything like going to Europe. Likewise, (66) is most commonly used to mean that I didn’t buy a book or do anything that would be considered in the context to be like buying a book.

In other cases we have seen, part:indef appears to be attached still higher in the structure, lending a feeling of “uncertainty.” For example, we might paraphrase (67) (repeating (22)) as ‘That a boat sank off Cape Cod is likely but not certain’ and (68) repeating (32)) as ‘That John likes cars and books is likely but not certain.’

Hyperlinks: Example 67

|

Lateral view (250K) |

Front view (183K) |

Close-up (246K) |

Hyperlinks: Example 68

|

Lateral view (216K) |

Front view (235K) |

Close-up (195K) |

In the normal course of cooperative conversation, a speaker will say only things that s/he believes to be true, and moreover, in the absence of any qualification, to be true for sure. If we allow for propositions to be true to varying degrees of certainty, we can characterize the contribution of part:indef as serving to allow consideration of degrees of certainty other than for sure. We can view this as another case of Widening, now on the degree of certainty with which the speaker regards the proposition to be true. We can think of “degree of certainty” in a sentence as being identified with the polarity of the sentence (where in the absence of a qualifier like part:indef, a negative sentence would be “false for sure” and an affirmative sentences would be “true for sure”); the extension here is that under certain circumstances, values between the two can be explicitly evoked.[12]

The indefinite particle may be used to widen the speaker’s degree of certainty with respect to a proposition. The sentence in (69) expresses that it ought to be the case that father will give the car to John, but at the same time expresses some doubt as to whether, in reality, this will happen. It is not that the signer isn’t certain about what he or she believes ought to happen, but rather that the signer isn’t certain that that father will give the car to John. [13]

Hyperlinks: Example 69

|

Lateral view (238K) |

Front view (266K) |

Close-up (261K) |

In these uses (as is clear in some of the other examples, as well), part:indef functions like a speaker-oriented adverb (akin to fortunately, certainly, or presumably).

The last function of part:indef we will consider here is its use in managing conflicts in the discourse. If evidence arises that participants disagree about the plausibility of a proposition or presupposition, part:indef can be recruited to assist. Consider (70) (repeating (17)), uttered in response to a question asking what color John’s car is.

Hyperlinks: Example 70

|

Lateral view (1.1MB) |

Front view (1.1MB) |

Close-up (1.5MB) |

By asking the question in the first place, the questioner implicitly indicates that s/he believes the addressee knows the answer. If this is not the case, one option the addressee has is to respond “I don’t know,” but (70) goes a step further: “I don’t know—but it’s not my fault, as I have no way of knowing.” The way (70) does this is by picking out the prototypical means by which the answer might be known (i.e., having seen the car) and asserting the falsity of this proposition and all propositions involving means like it (even perhaps non-prototypical means, e.g., psychic revelation) by which the answer might be known. This, too, can be seen as a Widening effect, in this case on the entire proposition itself (expanding the referent to the proposition and propositions deemed similar, given the context).

In a related use, consider a situation in which Mary asks John a question. The presupposition that led Mary to ask John such a question is her belief that he might know the answer. Suppose that Pete does not believe that this presupposition is plausible. Pete might say to Mary:

Hyperlinks: Example 71

|

Lateral view (1MB) |

Front view (1MB) |

Close-up (1.4MB) |

Here, part:indef is used to communicate the utter falsity of that presupposition: not only is it false that John knows the answer, anything (contextually) like John knowing the answer is also false.

It is not entirely clear whether a different kind of analysis is needed to account for the situations in which the particle seems to be associated with a presupposition or potential causality that is not explicitly stated. For example, compare (71) with (72). The meaning contribution of the particle is essentially the same in both cases; yet, in (72), there is no explicit negation in the sentence. Each of the examples is a denial of an implicit presupposition of the addressee. In (72), the addressee’s apparent belief that John might not know the answer is denied by the signer, with prejudice. It is clear that part:indef is mostly responsible for the disbelieving tone of such examples, but a formal solution based on a Widening effect in the pragmatic context has so far proved elusive.

This is in some ways similar to the example given in (34), repeated below as (73).

Hyperlinks: Example 73

|

Front view (4MB) |

Here, what is being highlighted is the disconnect between the indisputable reality and the expected situation. Whether such constructions should be analyzed as Widening, in a sense related to (but perhaps a bit different from) the others we have considered, or whether a different account would be more appropriate for these usages of the particle must be left as a question for further investigation.

To summarize, it appears that, in most cases, part:indef semantically associates with some layer of the linguistic structure (a determiner, a noun phrase, a predicate, sentence polarity, or an entire proposition) and “widens” the domain of reference, in some direction that is contextually appropriate. It is worth reiterating that the landscape of facts is still being explored, making certain details of the analysis necessarily preliminary; however, the overall pattern seems to fit well with the approach we have endorsed here.

5. Conclusions

We have described here a particle that occurs with great frequency in ASL but which has not been previously analyzed in the literature, to our knowledge. Its articulation is similar to, but distinguishable from, the wh-sign glossed as “WHAT.” Although this particle does occur commonly in wh-questions, it also appears in a variety of other environments in which wh-phrases are disallowed. Further study of the semantics, distribution, and use of this particle is warranted. We have argued here that this particle functions to widen the domain of items referred to by a focused wh-phrase or indefinite quantifier such as ‘someone.’ This particle may also be used in a comparable way with respect to other constituents in the sentence (e.g., NP, VP, CP) and we have suggested that the interpretation in such cases also involves semantic Widening along a contextually determined dimension.

6. Appendix

|

example |

explanation |

|

|

SEE, JOHN |

gloss (nearest conventional English equivalent) for a sign. Proper names in this paper are actually fingerspelled, but, for ease of presentation, this is not marked explicitly here. |

|

|

SHOW-UP |

multiword gloss for a single sign |

|

|

REAL/TRUE |

a slash is used when a single ASL sign has more than one English translation |

|

|

SOMETHING/ONE |

a sign in ASL that may be translated as either ‘something’ or ‘someone’ |

|

|

fs-HALL |

indicates that a sign is fingerspelled (H-A-L-L) |

|

|

#CAR, #BUS |

indicates a gloss for a fingerspelled loan sign. |

|

|

WILL^NOT |

^ indicates contraction |

|

|

“WHAT” |

a wh-sign produced with both hands extended, palms facing up, moving slightly from side to side |

|

|

part:indef |

an indefinite focus particle articulated with a single outward movement of one or both palms (facing upward) |

|

|

IX-1p |

pointing sign (used for pronominal reference); marked for first person |

|

|

IX |

pointing sign (used for pronominal reference); non-first person |

|

|

POSS |

a possessive pronoun, articulated with an open palm pointing toward the possessor |

|

|

non-manuals |

extended line indicates the domain over which the non-manual marker occurs |

|

|

whq |

wh-question marker (furrowed brows, squinted eyes, sometimes accompanied by a slight side-to-side head shake) |

|

| ____y/n JOHN GO |

yes-no question marker (includes raised eyebrows, forward head tilt) |

|

|

________neg |

negative marking (consisting of a side-to-side head shake and furrowed brows) |

|

|

formal notation |

||

|

ti |

trace coindexed with some moved element |

|

|

dominant and non-dominant hands |

||

|

Normally, the glosses in this article do not reflect whether the sign is 1-handed or 2-handed. The only exception to this is the part:indef, which is glossed as (2h)part:indef if and only if it is signed with 2 hands. |

||

|

In some cases, where the behavior of the non-dominant hand is, to some degree, independent of what is signed on the dominant hand, separate lines are used in the gloss to represent the unusual behavior of the non-dominant hand. The labels of [d] for ‘dominant hand’ and [nd] for ‘non-dominant hand’ are used, but in fact, the first line still may contain some predictable information about the use of the non-dominant hand. In this case, JOHN is a fingerspelled name sign, signed only with the dominant hand; LOVE is a two-handed sign. The divergence of dominant and non-dominant hand behavior is only as indicated by information on both lines. In this case, the particle is articulated first with the non-dominant hand: at the same time that the dominant hand signs WHO. Both hands complete the articulation of the particle at the same time. |

||

7. References

Baker, Charlotte, and Dennis Cokely. 1980. American Sign Language: A Teacher’s Resource Text on Grammar and Culture. Silver Spring, MD: T.J. Publishers.

Baker, Charlotte, and Carol A. Padden. 1978. Focusing on the Nonmanual Components of American Sign Language. In Understanding Language through Sign Language Research, edited by Patricia Siple, 27-57. New York: Academic Press.

Baker-Shenk, Charlotte. 1983. A Micro-Analysis of the Nonmanual Components of Questions in American Sign Language. Doctoral Dissertation, University of California, Berkeley.

den Dikken, Marcel, and Anastasia Giannakidou. 2002. From Hell to Polarity: “Aggressively Non-D-Linked” Wh-Phrases as Polarity Items. Linguistic Inquiry 33, no. 1: 21-61. doi:10.1162/002438902317382170

Emmorey, Karen. 1999. Do Signers Gesture? In Gesture, Speech, and Sign, edited by Lynn Messing and Ruth Campbell, 133-59. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gärdenfors, Peter. 1988. Knowledge in Flux: Modeling the Dynamics of Epistemic States. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hamblin, C.L. 1973. Questions in Montague English. Foundations of Language 10: 41-53.

Kadmon, Nirit, and Fred Landman. 1993. ANY. Linguistics and Philosophy 16: 242-422. doi:10.1007/bf00985272

Lillo-Martin, Diane, and Susan Fischer. 1992. Overt and Covert Wh-Questions in American Sign Language. Salamanca, Spain: Fifth International Symposium on Sign Language Research.

MacLaughlin, Dawn. 1997. The Structure of Determiner Phrases: Evidence from American Sign Language. Doctoral Dissertation, Boston University, Boston, MA. (available from http://www.bu.edu/asllrp/)

Neidle, Carol. in press. Language across Modalities: ASL Focus and Question Constructions. Linguistic Variation Yearbook 2.

———. 2002. SignStream™Annotation: Conventions Used for the American Sign Language Linguistic Research Project. American Sign Language Linguistic Research Project Report No. 11, Boston University, Boston, MA. (available from http://www.bu.edu/asllrp/)

———. 2001. SignStream™ A Database Tool for Research on Visual-Gestural Language. Journal of Sign Language and Linguistics 4, no. 1/2:203-214. doi:10.1075/sll.4.1-2.14nei

———, ed. 2000. ASLLRP SignStream Databases CD-ROM, Vol. 1. Boston, MA: American Sign Language Linguistic Research Project, Boston University, Boston, MA.

Neidle, Carol, Judy Kegl, and Benjamin Bahan. 1994. The Architecture of Functional Categories in American Sign Language. Talk presented at Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, May 1994

Neidle, Carol, Judy Kegl, Benjamin Bahan, Debra Aarons, and Dawn MacLaughlin. 1997. Rightward Wh-Movement in American Sign Language. In Rightward Movement, edited by D. Beerman (sic), D. LeBlanc and H. Van Riemsdijk, 247-78. Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Neidle, Carol, Judy Kegl, Dawn MacLaughlin, Benjamin Bahan, and Robert G. Lee. 2000. The Syntax of American Sign Language: Functional Categories and Hierarchical Structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Neidle, Carol, Stan Sclaroff, and Vassilis Athitsos. 2001. SignStream™ A Tool for Linguistic and Computer Vision Research on Visual-Gestural Language Data. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers 33, no. 3: 311-20. doi:10.3758/bf03195384

Nilsen, Øystein. to appear. Domains for Adverbs. Lingua.

Pesetsky, David. 1987. Wh-in-Situ: Movement and Unselective Binding. In The Representation of (in)Definiteness, edited by Eric Reuland and Alice G.B. ter Meulen, 98-129. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Petronio, Karen, and Diane Lillo-Martin. 1997. Wh-Movement and the Position of Spec-CP: Evidence from American Sign Language. Language 73, no. 1: 18-57. doi:10.2307/416592

Rizzi, Luigi. in press. Locality and Left Periphery. In Structures and Beyond: The Cartography of Syntactic Structures, volume 3, edited by A. Belletti. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

———. 1990. Relativized Minimality. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Romero, Maribel, and Chung-hye Han. 2001. On Certain Epistemic Implicatures in Yes/No Questions. In Proceedings of the 13th Amsterdam Colloquium. Amsterdam: ILLC/Department of Philosophy, University of Amsterdam.

van Rooy, Robert. to appear. Attitudes and Context Change. Manuscript to be published by ILLC/Department of Philosophy, University of Amsterdam.

[*]This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under grants SBR-9410562, BCS-9729010, IRI-9528985, IIS-9912573, IIS-0329009 and EIA-9809340. We are especially indebted to Ben Bahan, Mike Schlang, and Lana Cook for sharing their intuitions and ideas about this particle. This work has also benefited from discussions with Robert G. Lee, Sarah Fish, Carla DaSilva, Dawn MacLaughlin, Norma Bowers Tourangeau, and Jean Berko Gleason. We are grateful to Stan Sclaroff, Vassilis Athitsos, Murat Erdem, and Sarah Fish for their assistance in production of the video files illustrating the example sentences in this article. Authors’ names for this article are listed alphabetically.

[1] See, e.g., Petronio and Lillo-Martin (1997) for different claims about ASL questions from those presented by Neidle et al.(1997, 2000, e.g.) and summarized in this section.

[2] The distribution of nonmanual markings has been carefully analyzed using SignStream, a program designed to facilitate the linguistic analysis of visual language data by providing tools for on-screen display and analysis of linguistic information alongside of the actual video. SignStream is distributed on a non-profit basis to students, educators, and researchers, and the coded data are also publicly accessible. See <http://www.bu.edu/asllrp/SignStream/>. For further information about the Center for Sign Language and Gesture Resources, through which we have been collecting and distributing high quality video data (four synchronized views) plus linguistic annotations thereof (Neidle, ed. 2000), see Neidle, Sclaroff and Athitsos (2001) and <http://www.bu.edu/asllrp/cslgr/>.

[3] As discussed in Neidle et al. (2000:197 fn.10), multiple wh-questions are generally disallowed, except when the wh-phrases are strongly D-linked (Pesetsky 1987). However, there are constructions that involve more than one occurrence of a wh-phrase associated with a single questioned argument: an initial wh-phrase (which we have analyzed as a kind of topic) followed by a clause that contains a wh-phrase either in situ or at the right periphery.

[4] Thus, for example, the sentences in (5)-(8) have a presupposition that there was someone who was seen or who arrived, analogous to English sentences with intonational focal stress on ‘who’ in ‘Who arrived?’ or ‘Who did John see yesterday?’. See Neidle (in press) for an analysis in terms of leftward focus-movement followed by rightward wh-movement—subject to Relativized Minimality (Rizzi, e.g., 1990, in press)—in the derivation of sentences where the wh-phrase surfaces at the right periphery.

[5] See, e.g., Baker and Cokely (1980), Baker and Padden (1978), or Baker-Shenk (1983).

[6] This distinction was first observed by Lillo-Martin and Fischer (1992).

[7] There are two other ASL signs (which occur less frequently than “WHAT”) that can be used with the meaning of the English word ‘what’: #WHAT, a loan sign in which the English word is rapidly fingerspelled w-h-a-t, and another sign, often glossed as ‘WHAT’ (with single rather than double quotation marks), which is produced by brushing the index finger of one hand across the fingers of the other, open 5 hand. There are some differences in the distribution of these signs that have yet to be fully described (see Neidle et al., 1997:262 and fn. 24).

[8] In addition to the particle shown in these examples at the end of the sentence, it is also possible to have a second occurrence of the particle immediately following the verb THINK or SEEM (sometimes with a pause after the particle).

[9] As pointed out by Lana Cook (personal communication), this would include the situation where father died and, therefore, where it has become impossible for him to give the car to John. What is crucial is that there is at least the possibility that father will not give the car to John.

[10] In Emmorey (1999), this particle is considered to be a gesture and glossed as ‘/well-what/.’ Although it is not entirely obvious how the distinction between sign and gesture should be defined, even by the criteria provided by Emmorey, part:indef does seem to pattern with linguistic signs (rather than gestures) by virtue of systematicity of form, distribution, and meaning.

[11] While in this respect, part:indef is similar to “...he hell” in English wh-questions (as discussed by Pesetsky (1987), den Dikken and Giannakidou (2002)), it does not appear to be as “aggressive” in its domain-widening.

[12] This type of “Bayesian belief model” has been explored by several authors; see, e.g., Romero and Han (2001), Nilsen (to appear), van Rooy (to appear), and particularly Gärdenfors (1988).

[13] This is perhaps similar to the English “Father certainly must give the car to John” (noting that, perhaps counter-intuitively, one of properties of the speaker-oriented adverb certainly is that it introduces a small degree of doubt; compare ‘Audrey died in the explosion’ with ‘Audrey certainly died in the explosion’).

[ Home | Current Issue | Browse the Archive | Search the Site | Submission Information | Register for Updates | About | Editorial Board | Site Map | Help ]

Published by the Dartmouth College Library.

|