Volume 4 Issue 1 (2015) DOI:10.1349/PS1.1938-6060.A.454

Recipe for Laughs: Comedy while Cleaning in The Wife Saver

Jennifer Hyland Wang

HELLO, GIRLS! Well, here we are at the end of the week, which is just fine as far as I'm concerned. What better time to talk about little Rollo and his sister Susie. I start this thing in the solemn hope that you're still feeding the children, there being no point in having children unless you feed them. A hungry child can never be trusted.1 (Allen Prescott in The Wife Saver, 1932)

Radio host Allen Prescott's cynical comic perspective on domestic life was formed during his early banishment from local prime-time radio. His career-defining role as "the Wife Saver" began, the story goes, because Prescott complained too loudly and too often about his billing to WINS station manager Clark Kinnaird.2 Annoyed by Prescott's constant visits to his office, one day Kinnaird exploded, yelling, "'Get the hell out of here and do the household hints.'"3 To punish his young news announcer, Kinnaird demoted Prescott to daytime in 1929.4 It was there, in purgatory, that Prescott's career as the Wife Saver was born.

Allen Prescott developed a distinctive daytime blend of comedy and household hints in the program he was obliged to host, The Wife Saver. While working on the very first script, Prescott came up with the idea that would distinguish his series:

His sense of humor got to work on the "household hints" he had collected. He ran in comments about them, often as wisecracks. The script rambled into nonsensical ramifications. Gag piled on gag. The script turned out a riot of fun in a mine of information.5

Combining practical tips, snarky asides, and a sympathetic shoulder for America's housewives, The Wife Saver distinguished itself from other homemaking programs and most daytime fare. Words like radical and revolutionary were bandied about in the contemporary press to describe the program's presumption that women had a sense of humor or the program's conceit that a man could helm a homemaking program. 6"THE IDEA of a man telling women how to do their housework and then kidding them about it," a reporter from Broadcasting announced confidently at the series' debut, "has set a new precedent in household programs."7Indeed, there was consistent commercial interest in Prescott's innovative address to America's housewives. The Wife Saver aired locally in New York before moving to an NBC morning slot on October 8, 1932.9 Sometimes sustaining, but often sponsored by soap companies, The Wife Saver aired for fifteen minutes, often multiple times a week, on NBC's Blue Network for much of its eleven-year run as well as on CBS twice a week between 1936 and 1937. (Figure 1) Even after its cancellation on network radio, The Wife Saver lived on in the postwar era on transcription and in brief runs on local and network radio and television.10

However, despite such optimism in the series' novelty, neither the show's eventual success nor its longevity would significantly change programming practices for female listeners in the day. Daytime comedy was a relatively endangered genre throughout the history of network radio. Though broadcasters struggled to find programming to woo advertisers and to connect with a largely unknown and unseen female audience, comedy programs were rarely considered to fill the void of unsold daytime hours. Although the popularity of prime-time comedy and variety shows soared throughout the 1930s, comedy programs were pushed to the margins of the daytime schedule. Even when critics complained that the networks needed to add diversity to daytime schedules overrun with serials, few comedies made it to air.11 The humorlessness of daytime radio in 1943, when The Wife Saver ended its network run, closely resembled the sober tone of daytime programs in 1932. Over the past ninety years of American broadcasting, these programming patterns have persisted. Industrial assumptions about audiences, daytime schedules, and generic structures based on ideology and circumstance rather than actual demographic research shaped early broadcasting practice and soon solidified into industrial common sense. Even in today's universe of many media channels, platforms, and formats, comedy during the day remains a rarity. The noted absence of daytime comedies serves as a reminder to historians how hard it was for broadcasters to imagine women laughing during the day.

Why study, then, a generically innovative program that spawned few imitators in the realm of daytime radio? Although the influence of The Wife Saver was not widespread, the program's precarious position in daytime, its survival on the margins of the broadcast schedule, and its negotiations of the generic and gender logics of daytime on the periphery of industry practice makes The Wife Saver a valuable object of study. As evidenced by the sheer volume of industrial discourses generated by The Wife Saver, there was something dangerous about the distinctiveness of the program. Throughout the series' eleven-year run, the press was alternatively amazed and unnerved by the program's success. As ideas about female audiences, generic structures, and broadcast schedules were being negotiated in the early 1930s, Prescott's fresh approach to entertaining housewives touched a nerve in Depression era America, unsettling a daytime genre that spoke about women's domestic labor and testing the industry's beliefs about daytime programming.

The steady discursive interest in Allen Prescott and The Wife Saver suggests not only the culture's sensitivity to the issue of gendered labor, but to the subversive nature of humor aimed at a female audience. While broadcasters sought to prioritize women's assumed interests and issues in daytime programming, they also wanted to maintain the gendered division of labor in the home from which broadcasting profited. That Prescott's humor was aimed at female listeners working in their homes threatened both the gendered logics and the economic machinery of daytime. The discursive interactions produced by the comic perspective, promotional strategies, and industrial reception of The Wife Saver make visible the generic and gendered system that evolved to manage industrial and cultural anxieties about radio's daytime address. A study of the discursive ruptures produced by the radio host Allen Prescott provides scholars with insight into the genealogy of daytime genres and why daytime comedy was such a rare species.

In this essay, I explore why the networks consistently chose tears over laughs in programming to daytime female audiences and the tensions created when commercial radio's investment in sustaining the gendered order of daytime was challenged by the use of humor. Using the archives of NBC, the papers of radio star Allen Prescott, and contemporary trade and popular press, I examine how The Wife Saver comically interpreted the generic features of daytime homemaking programs.12 The very hybridity of the program—a common daytime genre mixed with comedy, and a male host presiding over a feminized genre—provides a lens to view radio's early relationship to comedy, to women's work, and to female listeners. The program's innovative blend of a rigid generic structure, dark domestic humor, and a mutable, gendered host negotiated the industrial and ideological tensions caused by comic work in the daytime. Through an analysis of the transgressive potential in The Wife Saver's humor and the gendered persona created by Prescott, this study ultimately reveals the narrow parameters on the mirth manufactured during the day, the role played by commercial culture in sustaining a separate system of gendered labor, and a rationale for daytime radio's limited use of comedy.

No Room for Laughs: The Marginalization of Comedy in Daytime Radio

Contemporary nostalgia celebrating "the golden age" of network radio comedy has largely obscured the uneasy relationship between radio and comedy in the earliest days of the medium. In the highly speculative period of the 1920s and early 1930s, neither local nor network broadcasters saw comedy as ideal programming to fill the open spaces in its developing evening schedule. As regulators and audiences demanded more diverse offerings than music in the evenings, broadcasters saw in vaudeville a pragmatic template for the development of nighttime comedy. The genre of radio comedy evolved, incrementally and through trial and error, as producers, writers, and comedians tried to translate the broad comedy and distinctive regulated experience of vaudeville to the aesthetics, production practices, and financial models developing in early radio. The vestiges of vaudeville embedded in prime-time radio programming—the broad, often self-reflexive humor and the gendered address—limited the possibilities for comedy offerings in the daytime.

Live comedy as practiced in vaudeville and other popular entertainment, many worried, would not conform to the conditions, practices, and constraints of the newly national medium.13 In analyses such as "Why It Is Difficult to Be Funny over the Radio" (1926), the press enumerated the many obstacles facing radio comedians.14 The radio entertainer's ability to ad-lib, creating humor "flowing out of the situation of the moment," was unduly constrained by the "iron laws of time that radio has imposed on itself."15 Radio's insatiable demand for new material week after week tested the joke collections and stamina of gag writers, as comic material mined in vaudeville over many years and many miles evaporated through the ether in a matter of minutes. The oft-repeated phrase, "Ten Years in Vaudeville, Twenty Minutes in Radio," described the pessimistic attitude common among radio entertainers and early broadcasters about the future of comedy on radio.16

The inability of the comedian to be seen by or to "see" the audience also challenged the mechanisms of audience control perfected in live stage comedy. Onstage, the professional vaudeville performer used well-honed material, his body, and his voice to elicit laughs from the local audience before him. "Stripped of funny antics, stage props and laugh-winning gestures," commented New York Times radio reviewer Orrin Dunlap in 1933, the radio jester "worked blind" on radio, relying only on his voice to get over comic bits.17 The alienation of the radio comedian, disconnected from his audience, was vividly depicted in 1929 by journalist Genevieve Cain; as the radio entertainer steps before the microphone,

no warming burst of applause greets his entrance, no spot light turns on him when he issues from the wings, no giggles tell him his audience is waiting for his antics . . . In addition there is a frigidity that awaits him at the other end. The radio audience is not assembled in one theatre, where one gusty haw-haw will start an avalanche of laughter. It is segregated into small, inhospitable units, as inimicable to spontaneous merriment as a stage hand.18

Scattered across the nation in private homes, the radio audience was not a "crowd" with a "group mind" that could be manipulated by a skilled comic artist.19Without a crowd to observe, the radio comedian could only imagine what these families might find funny and felt obligated to avoid any kind of humor—too local, too ethnic, too racial, or too sophisticated—that this invisible audience might find offensive. Restricted in content, practice, and relationship with their audience, radio comedians found it difficult to curb humorous excesses or ensure audience satisfaction. Comedy, beyond the control of the lone radio performer, became even riskier on air.

While the efficiencies, routines, and oversight of mass-produced network comedy offered a measure of control over the reception of broadcast jokes, radio comedy remained a threatening, even dangerous, entity over the air. Mae West's risqué performance in a 1937 Garden of Eden skit during The Chase and Sanborn Hour vividly demonstrated the limits of the industry's checks on comedic excess.20 The discursive anxiety expressed in the press about the radio comedian's relationship to his unseen audience spoke to the industry's fear that it could not regiment the experience of the radio audience. Keeping listeners aligned with the comic intent and commercial function of the program was ultimately the responsibility of the radio comedian. The radio entertainer had to perform within a narrow set of parameters; to keep commercial sponsorship and a network time slot, the radio jester needed to conform to standards of public service and common decency, while simultaneously attracting listeners with new material and a "fresh" perspective. The difficulty he had in doing his job, however, made the proliferation of comedy programming problematic. For on-air comedy to develop, radio needed new generic structures that could better manage comedy's discursive volatility.

In this formative period, broadcasters experimented with comedic formats, adapted from vaudeville, which could triangulate audience interests, sponsors' needs, and radio aesthetics.21 At first, comedy was interspersed in radio's popular music programs as orchestra leaders and announcers joked with one another between musical selections.22 This informal practice—breaking up the musical monotony of one song after another—eventually led to the establishment of song and comedy patter teams, a staple of small-time vaudeville houses, to add variety to evening schedules.23 Incidental comedy—orchestral music bookended by jokes or skits—limited the impact of comic barbs, but the format strained the joke books of gag writers and the road-tested routines of vaudevillians. Some of the earliest attempts at full-length prime-time comedy programs were burlesque comedies such as NBC's The Cuckoo Hour (1930-32) or CBS' The Nit-Wits (1930-31) that parodied radio genres, conventions, and performers.24 Although radio itself was initially a fertile field for satire, this conceit was difficult to sustain over time. The comedy-variety format, a marriage of vaudeville skits and nightclub performances anchored by a central personality or team, was a better adaption to the weekly cycle of radio production.25 Offering a recurring cast of characters and skits sandwiched between musical numbers, these popular programs by vaudeville entertainers such as Jack Benny and Eddie Cantor provided the variety expected of national networks, an intimate rapport between the unseen audience and the characters they had come to know, and a generic structure that would aid the host in negotiating the boundary between permissible subversive humor and comedic excess. With these innovations, the comedy-variety genre multiplied on prime-time schedules.26

Although vaudeville's physical comedy and ability to play to the audience was inevitably altered in its interaction with radio, stage comedy left a lasting influence on network comedy norms. Vaudeville's broad physical humor was moderated on air, but its emphasis on wordplay, puns, character-based humor, and imagined comic situations shaped network comedy offerings. Stage comedy, suggests historian Michele Hilmes, lent prime-time radio a self-reflexive humor aimed at a family audience at leisure.27 What also endured, as air comedy evolved from vaudeville, was comedy's gendered address. Through the voices of male orchestra leaders, song and patter men, and the predominantly male on-air comedians, a male comic perspective permeated prime-time schedules. Women, even when they did appear on these early radio programs, were more often the objects of humor than the purveyors. As programmed in the evening to a mixed, but male-dominated audience, radio comedy was inevitably gendered.

Comedy programming suited the industrial logics of daytime radio even less well than it suited evening hours.28 First, the attentiveness required by comedy programs endangered the tenuous balance between radio listening and domestic duties envisioned by broadcasters, and suggested a leisure rarely offered explicitly to female listeners in early radio. Second, comedy programming did little to advance the intimate, commercial relationship deemed essential between advertisers, radio, and housewives. Comedy played to a crowd; the serials and homemaking programs that came to dominate daytime schedules spoke directly to the housewife listening alone to her set.29 Third, comedy all too frequently exposed the artificial intimacies that daytime radio tried to engender. In daytime programming like serials, one ad man observed, "every extreme is adopted to prevent the feeling of artificiality or 'show' from obtruding itself on the consciousness or sub-consciousness of the listener."30 Given the self-consciousness and reflexivity characteristic of prime-time comedy, comedy not only played with the boundaries between what is public and what is private, what is real and what is artifice, but also highlighted them. Finally, the masculine cast of radio comedy made it difficult for producers and writers to conceptualize a program that could reconcile radio's gendered comic address with a female host and a female daytime audience. The programs deemed effective in speaking to the lonely, impressionable daytime listener were those that simultaneously exploited the powerful intimacy of radio for commercial gain without violating traditional gender ideologies and practices. Comedy, offering an escape from the indignities of daily domestic duties, could not fulfill that promise.

| 1927-28 | 1930-31 | 1934-5 | 1938-39 | |

| Daytime Comedy Drama | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Daytime Comedy Variety | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Prime-time Comedy Drama | 0 | 5 | 3 | 6 |

| Prime-time Comedy Variety | 2 | 5 | 13 | 16 |

Thus, throughout the history of local and network radio schedules, comedy programming has never been more than a mere fraction of the shows offered for housewives' consumption during the day. Comedy was, admitted one radio writer in 1937, "a minus quantity in the morning and afternoon shows."32 Indeed, despite a brief experiment with comedies in 1934, the amount of daytime comedies on CBS was only 6 percent in 1936.33 Even though comedy-variety programs were some of the most popular evening shows by the mid-1930s, the networks repeatedly turned to other programming forms—musical programs, homemaking talks, and serials—to fill daytime hours.34

When comedy was programmed during the day, shows with humor were marginalized. Comedies or daytime programs featuring comedy could often be found at the periphery of the daytime schedule when a "mixed" audience was more likely—in the early morning hours as other family members got ready for the day, or in the late afternoons when women and children home from school were available to listen. Early morning clock shows such as the Quaker Oats Early Bird Program or the long-running The Breakfast Club offered some chuckles nestled between weather reports and time announcements.35 The comedy in these programs, as discussed by Alexander Russo, was literally contained, framed by time announcements that helped housewives ready their families for work and school.36 Like the earliest prime-time experiments in radio comedy, comic bits were embedded in existing daytime formats. Broadcasters and sponsors found incidental entertainment, say light comic banter squeezed between songs, more palatable in the day than the broad comedy becoming so popular at night. By placing comedy at the margins of the schedule, in between musical numbers, or ensconced within familiar genres, broadcasters provided the diversity that appealed to regulators and audiences, upheld the primacy of women's domestic labor, and mitigated the destabilizing effects of radio comedy. The assumption that "humor is at odds with the very definition of womanhood" was embedded early in industrial practice.37

Generic Innovations and Negotiation in The Wife Saver

To appeal to audiences, sponsors, and industry executives, Allen Prescott had to negotiate the gendered and generic conventions of daytime radio as well as contemporary attitudes about women and humor. Relying on sarcasm, wordplay, and gags sandwiched between household tips, Prescott's The Wife Saver brought prime-time humor into the daytime and into a genre dominated by women. The Wife Saver offered housewives a break from the monotony of their duties as well as a comic perspective on their domestic routines. However, Prescott's daytime comedy program also challenged the tenets of daytime, the gendering of radio humor, and the generic strength of the homemaking program. The generic force of The Wife Saver, I argue, worked to mute the sarcastic humor directed at domestic life for female audiences and rendered the relief offered to housewives fleeting.

The Wife Saver shared the generic frame and commercial intent of typical homemaking shows. Daytime homemaking programs were early staples of local and network daytime schedules.38 The basic generic features of homemaking programs—a sober tone, authoritative guidance, practical help for the housewife, and a dependable female hostess guiding listeners in modern domestic practice—helped broadcasters and sponsors engineer consumer tastes and provide the "service" essential to broadcasters' conceptualization of daytime programming. Prescott, the radio program's sole writer, fashioned his program to hew closely to this newly popular formula.39 Divided into seven distinct parts, alternating music, household hints, and commercial spots, The Wife Saver offered the diversity prized by broadcasters and made it "possible for advertisers to work in copy boosting their products in a very inoffensive way."40 Akin to other daytime programs that offered housewives advice on effective domestic practice, the hints offered by Prescott—how to keep celery fresh or how to erase marks from walls—nodded to the principles of scientific management in vogue at the time.41 Although Prescott was not a household expert himself, he relied on the wisdom of "female authorities"—his own listeners—to mail in the practical hints he would incorporate into each script. Prescott encouraged a chummy relationship with the nation's housewives; opening each program with a warm, "Hello, Girls," Prescott repeatedly addressed his audience as girls, sometimes up to a dozen times in a five-page script, to cultivate an intimate friendship with his listeners.42

The Wife Saver consciously navigated one of the main challenges facing daytime entertainment: how to attract housewives to the radio and yet permit their domestic duties to proceed. The program's structure—alternating musical selections with household hints—theoretically permitted women to stop for a moment to listen and then continue their work during the musical interlude. The ending of every episode of The Wife Saver spoke directly to this dilemma. Before signing off each episode, Prescott would say, "Don't Forget, Mrs. Housewife, I hope there's nothing burning, this is Allen Prescott, The Wife Saver."43 While suggesting that the program had been so entertaining that it had distracted the listener from her duties, this closing gently reminded her to get back to work. In fact, according to several press reports, Prescott's timely warning purportedly saved a dinner or two.44 In this daytime context, Prescott provided service commensurate with the distraction, skillfully negotiating the intrusions caused by radio's daytime address and reinforcing the primacy of women's domestic labor in the home.

Yet, The Wife Saver's novelty—its blend of comedy with homemaking tips—offered a marked shift in tone from traditional home service shows. Prescott's vocal performance was often sarcastic; he spoke deadpan, "at high speed, with no waits for laughs," moving from topic to topic so quickly that he sometimes stumbled over his own words.45 The humor of the program, as evidenced by existing scripts and program reviews, was dark, cynical, and slightly malicious.46 In hints about the importance of preserving vitamins in the food you serve ("destroying vitamins is just as silly as throwing away Aunt Ella's insurance money, after you waited so long") or how to handle leftovers ("Never throw anything away, even your second husband, until you think about it"), Prescott surveyed the domestic landscape with a cynical eye.47 His juxtaposition of "uproarious informality and useful household information" was not only, one reporter concluded, an "amusing variation of the usually dead-serious household service blocks," but, as suggested by another, "endear[ed] him to an audience perhaps a little weary of the more didactic and heavy-handed programs of some of his feminine colleagues in the morning-radio arena."48 Prescott's "whimsical approach to the minor perplexities which beset the home" forged a new relationship between daytime listeners and their homemaking host.49

Although the jokes in The Wife Saver had a structural function, to break up a stream of twenty-second household hints, some contemporaries suggested a psychological function for these snarky remarks. As explained by New York Times radio critic Orrin Dunlap Jr., one of the "backbones of radio humor" in 1934 was outlet comedy:

[B]ased on daily experiences, it is called "outlet comedy" because it is an outlet for human emotions . . . Human tension is often broken by a simple gag that diverts the mind. A complete, sudden reversal of thought or a burst in the stream of emotion is like "stopping a sixty-mile-an-hour motor car on a dime." It jolts everybody.50

Though Dunlap's account succeeds in describing the jarring rhythm of Prescott's flippant asides and perhaps the ephemerality of prime-time radio comedy, the concept that outlet comedy was a mere diversion for listeners oversimplifies the complex operation of the series' humor. In one episode, Prescott linked a hint about making a tie rack with a disparaging comment on the fidelity of husbands:

[W]ould you like to make a non-slip tie rack? In that case put a couple of cup hooks on the back of the door and stretch a rubber band between them, one that's about an inch wide, and your husband's ties won't slip. Would that you could be as sure of your husband.51

Moving abruptly from the pragmatic to the comic, Prescott's humor is momentarily diverting, acknowledging a housewife's deepest fears and quickly clipping her laughter with yet another household tip. However, the prime-time comic sensibility of Prescott, the series' singular focus on domestic targets, and the cumulative impact of outlet comedy over the course of multi-weekly broadcasts suggests that the humor in The Wife Saver was more subversive than contemporary discourses acknowledged.

The domestic target of the humor in Prescott's The Wife Saver distinguished the series from other prime-time and daytime offerings. Unlike network predecessors such as The Cuckoo Hour or Sisters of the Skillet, in which male comedians mocked the female experts of homemaking programs, The Wife Saver lampooned domesticity itself. Featuring little to no commentary on politics or current events, host Allen Prescott mined the comic potential in the frustrations, irritations, and expectations placed on America's housewives. In her discussion of the comic televised performances of Lucille Ball and Gracie Burns, Patricia Mellencamp uses Freud's analysis of "gallows jokes" to illuminate the comic possibilities of domestic-centered situation comedies.52 Although postwar women in America's homes and the comediennes trapped on domestic sets could change their fate perhaps no more than the joke teller at the gallows, Mellencamp suggests, domestic humor recognized women's oppression in the domestic sphere and offered viewers an imaginary escape from the strictures of domesticity. Joanne Gilbert, in her study of female stand-up comics, argues for the subversiveness of humor from the social margins:

[B]y transgressing boundaries and inviting women to be the laughers rather than the laughed-at, [female comics] are attacking hegemonic power and privilege in the public sphere.53

The comedy of The Wife Saver functioned similarly to that of the female comics analyzed by Mellencamp and Gilbert. Instead of making fun of the women who gave household talks, Prescott's The Wife Saver acknowledged women's discontent with the routinized and relentless labor of the domestic sphere and encouraged female listeners to laugh at the unrealistic domestic standards governing their lives.

Some of the subversiveness of Prescott's humor lay in how comic asides unearthed the suppressed emotions of women's lives. Nancy Walker argues that hostility, however muted, was an essential component in much of the history of women's domestic humor.54 Mellencamp, in her study of early televised domestic comedies, demonstrates that the humorous situation is "'dominated by the emotion that is to be avoided,'" anger.55 So, too, was The Wife Saver's humor governed by women's domestic discontent. Women at home were under siege—stalked by hungry children, hounded by boorish husbands, and exasperated by unexpected visitors.56 And women in the domestic scenarios conjured by Prescott were angry, kicking roasts down cellar steps, attacking flour sacks with meat cleavers, and cursing freely.57 For example, in a hint about making cracker crumbs, Prescott reminds his listeners,

[R]emember if you've pounded [the crumbs] with a hammer or the flat side of an axe, you have in your hand an implement that gives you an excellent chance of winning any arguments that come up at the moment.58

Although listeners are invited to laugh at this possibility, this wisecrack both acknowledges listeners' frustrations and imagines a domestic power they didn't know they had. Exposing the "pretty dark thoughts" of the "kitchen-captives," The Wife Saver gave voice to the hidden emotions of Prescott's imagined female audience and brought those thoughts repeatedly into public view where they could be shared with other listeners.59

Often, Prescott's gags offered housewives comic fantasies to escape the drudgery of their daily lives. At times, the comic remarks integrated into the program voiced dark temptations. His baby advice ("Sometimes its difficult to know what to do with baby. This could lead to your throwing him away and thats so hard to explain so I hasten to tell you that his baby carriage is a good place to park him even indoors." [sic]) envisioned one way to handle the demands of motherhood.60 A hint about buttoning the cuffs of your husband's shirt to the front to keep the sleeves from tangling on the line became an occasion for the housewife to imagine, "depending on how you two are getting along," what her husband would "look like stretched out with his arms crossed over his chest."61 Under the guise of comedy, The Wife Saver gave housewives the opportunity to fantasize an escape from domestic work and family obligations. Often, the humor in The Wife Saver transmitted an edginess that belied the series' generic conformity.

The contrast between the humorous and often sympathetic acknowledgement of the difficulties of domestic duties paired with hints to ease women's labor revealed the performativity of domestic ideology. In a 1933 program, Prescott gave his listeners a baking hint and a reminder that all is not what it seems:

Beside that while you are fooling around the kitchen remember to add a teaspoonful of cornstarch to your meringue it will keep it firm. Nothing like a firm meringue. Remember in Hollywood in the early days a bit of firm meringue in the right spot made many a star's career.62

In the program's hints, Prescott made visible the often invisible labor of housewives and empathized with their plight. Once, when passing along a backbreaking suggestion to clean area rugs, Prescott commiserated with the exhausted housewife at the hint's conclusion:

Later, after the osteopath has gone home, you can lie in your bed and look at yards and yards of clean rugs, with a thankful gleam in your eye. The eye that you have energy enough to open.63

The Wife Saver recognized how lived experience—the daily indignities and physicality of women's labor—deviated from gendered ideals and broadcast that gap to a national audience.64 In this sense, The Wife Saver becomes part of a long tradition of American women's humor that "commonly deals with the central (female) figure's attempt to meet or adhere to such [social] standards" and to inevitably fall short.65 The domestic scenarios created by Prescott on air validated women's experiences and invited listeners to laugh at the effort required to be the ideal housewife.

The sheer volume of the domestic humor in The Wife Saver makes it difficult to dismiss these critiques as mere diversions. An essential component of prime-time radio comedy, argues Hilmes, was a "resistant humor" that ridiculed American social standards, institutions, and cultural norms.66 As translated from prime time to daytime, Prescott's cynical comments about women's work functioned, like most humor from the social margins, to call "cultural values into question by lampooning them."67 Bombarded with jokes about life on the margins of a man's world, female listeners, dispersed throughout the country, were prompted to "see" the painful reality of their domestic context and, more significantly perhaps, to imagine solidarity with others similarly situated. Further, Prescott, allowed a daytime comic perspective unavailable to a female host, gave authority to these domestic musings.

Yet, despite the dark humor of the series, The Wife Saver was a commercial daytime feature, designed to operate within a broadcast system tightly linked to traditional social and gender ideologies. The program was planned, as articulated by Frank Nagler in his 1938 text Writing for Radio, "as a means of relief from tension or monotony" for America's housewives.68 The introduction of a spec script for the program best expresses the intended psychological release offered by The Wife Saver:

Hello girls! This is Allen Prescott, the wife saver. It is to be supposed that no one has offered to take you away from it all, so the best we can do is to keep it all from taking you away.69

The Wife Saver afforded female listeners only a temporary reprieve from their duties, a humorous diversion from housewifery lasting the length of each episode. Indeed, the generic force of the program was to make housework more manageable.70 His hints offered not an escape from labor, but a way to handle the labor one must perform. For example, when Prescott suggested that women find a new way to do an old household chore, he claimed that doing so would "leave you wide open to find something else you'd rather not do."71 While he sympathized with the relentlessness of women's work in the home, Prescott's solution—yet another radio hint—preserved both the separate gendered spheres and the commercial system that depended upon it.

The generic elements of this hybrid homemaking show also worked to mitigate the transgressive potential of these comic comments. In the course of the series, Prescott used hints to help housewives manage their "dark thoughts" and avert domestic disaster. Preparing in advance for the time when one's husband brings the entire office home unannounced for dinner, Prescott assured his "girls" that this tip would keep them from taking "an active dislike to what was once a perfectly good husband."72 In one 1941 episode, Prescott warned that failing to organize one's cleaning had consequences beyond their own exhaustion:

[W]hen you upset the whole house the family's liable not to come home at all. It isn't quite fair to have them wandering around like a bunch of gypsies with no place to sit, stand or even lie down. The dismal picture of poor Father with his aching back braced against an upturned chair roasting a hot dog on a stick in the fireplace, is pretty sad. The children all snuggled together in the bath tub because there's no bed to lie on, is much too forlorn.73

While valorizing homemakers' efforts and validating their work, this humorous scenario of a family impoverished and displaced reminded women to better organize their cleaning. Providing a rationale for both the program and women's domestic duties, The Wife Saver emphasized the importance of women's housework and their critical role in keeping the American family intact.

The generic blend of comedy and cleaning developed by Prescott offered both a progressive outlook and a restrictive frame on the ideological system upon which the radio industry relied. Appealing sympathetically to overworked housewives, the comedy of The Wife Saver called listeners to their radio set, offering them laughs and a break from their daily routines. Although Prescott publicized the anger, frustration, and boredom of the nation's housewives, predating a critique of the stereotypical gender roles that would later make Betty Friedan and her book The Feminine Mystique household names, the aim of the show was not revolutionary. Offering its hints as the means by which gendered labor becomes tenable, The Wife Saver muted some of the destabilizing effects of its comedy—that its expressions of revenge, dark thoughts, and escape from social conventions could be taken seriously. Thus, Prescott's ability to "save wives" was necessarily limited in daytime radio. The Wife Saver could save wives, for example, from an unorganized domestic routine, but not from the sharply divided system of gendered spheres organizing contemporary society.

Thus, the generic frame of the program and its use of comedy maintained the tension created by radio's daytime address into women's workplaces. Listening at leisure was a privilege offered to prime-time audiences, but The Wife Saver didn't offer such an option to daytime listeners. To thrive, the program needed a female audience overworked, unappreciated, and eager for a laugh. While the ceaselessness of women's work in the home was an industrial obstacle in daytime radio, it was also a necessary premise for The Wife Saver. The program needed women in the home, lured to their sets by Prescott's cheeky remarks, the chance to be a part of a community both sympathetic and knowing, and enjoying the brief reprieve from their domestic tasks. The generic frame of The Wife Saver absorbed the impact of much of Prescott's cynical asides, the interruption of women's domestic duties, and the vicarious movement across public and private spaces regularly occurring in this hybrid program. Though Prescott designed the program to appeal to women, The Wife Saver consistently prioritized the commercial function of the series and the primacy of women's domestic labor.

Women Can Laugh? Male Hosts and Gender Dysphoria

Humor was scarce in daytime, but The Wife Saver's other major generic innovation—a male host of a radio homemaking program—was even more rare. Although there has been a long history of male experts giving advice to women, radio homemaking programs had handed that power exclusively to women.74 Defying those in the industry who warned that women didn't have a sense of humor, Prescott told Broadcasting that he had a "hunch that it would amuse women to hear a man tell them short-cuts in housework."75 "Dish[ing] up household hints in the flippant, fly style of a vaudeville single," Prescott brought the public, masculine world of vaudeville into homes during the daytime.76 These innovations, however, were a dramatic breach of daytime conventions, threatening both the generic function and ideological work of daytime radio. News features on The Wife Saver sought to recuperate the threat of the program's humor and negotiate the complex interaction between gender and genre in daytime programming. The dynamic discussions circulating around the host Allen Prescott and The Wife Saver illustrate how troubling it was to mix gender, genre, daytime, and comedy.

For the mostly male press corps who wrote about The Wife Saver, Prescott's successful, boundary-busting move to radio homemaking was itself comic. The "unnatural" arrangement—that Prescott could be the host of a homemaking show—challenged rigid definitions of masculinity. The press found it necessary to identify Prescott's appeal and rationalize the program's success.77 Housewives liked Prescott, one reporter suggested, "because he packs a giggle into every gurgle of the tea kettle and nonsensically makes sense to them as he manhandles a subject they know only too well."78 Within the interpretive framework of a "natural" separation between gendered spheres of labor, a man helping women with housework was both socially and industrially incongruent. Within the interpretive framework of a "natural" distinction between homosexual and heterosexual masculinities, Prescott's close relationship with his female listeners needed to be reframed. The program was hilarious, the press reasoned, because of the peculiarity of the show's conceit, not the domestic jokes Prescott inserted into the script. That a man could be a household expert and that women would tune in to hear that man "manhandle" housekeeping hints was simply, offered one reviewer, "too funny for words."79 Perhaps revealing an unspoken homophobia, reporters took great pains to emphasize that Prescott was not peculiar, his day job was.

In this context, the contemporary popular and trade press found the program's popularity disconcerting. The success of the show unsettled assumptions that women neither enjoyed nor understood humor during the day. In reviews of The Wife Saver, critics focused obsessively on how strange it was that women responded positively to the program. The subtitle of a 1932 article—"Allen Prescott Finds Housewives Have Sense of Humor; They Like Mere Male's Advice on Domestic Problems"—described the press's surprise at the "feminine psychology unearthed by Allen Prescott."80 The program, argued one reporter, had even surprised female audiences; The Wife Saver simply "bowled over the housewives, who never expected they'd be listening to a man telling them how to run their homes."81 Prescott's crossing of the gendered divide clearly challenged radio's imagined relationship to its female audience, disturbed industrial common sense, and defied rigid cultural notions of men's and women's work.

Thus, despite the strength of the ideological framework that governed daytime radio, merely substituting a male host for a female host in a homemaking program tested the generic boundaries. The daytime homemaking program was so thoroughly gendered, featuring female experts speaking to female listeners about shared private duties, that this kind of generic innovation was troubling. A local journalist explained the intense interest in The Wife Saver this way: "[W]omen have often taken over men's jobs. But when a man takes over a woman's job, that's news."82 A widely used publicity photo for The Wife Saver animated the concept that a man could not be an authoritative guide to homemaking. (Figure 2) The photo depicts a disheveled and exhausted Prescott, sitting on an easy chair, bare feet, suit pants rolled up, and napping amid an assortment of brooms and mops.83 The caption reads, "Alan Prescott of NBC's 'The Wife Saver' program demonstrates how useful a man can be around the house."84 Prescott's presence in the world of daytime homemaking subverted the generic force of the program and raised questions about the work Prescott could "naturally" do in the daytime. The industry's explanationThe Wife Saverthat Prescott, as a man, could not possibly be helpful in the homeThe Wife Saverhighlighted the comic nature of his daytime work to repress Prescott's threat to distinct notions of masculinity.

Forced to negotiate gender, genre, commercial, and comedic boundaries, Prescott was a unique male presence in the daytime. In her discussion of the daytime television hosts Gary Moore, Art Linkletter, and Arthur Godfrey (affectionately called "the charm boys" in the press), Marsha Cassidy describes how these "interlopers in a subaltern sphere allotted almost entirely to women" offered "a modulated form of masculinity" on television that viewers felt comfortable welcoming into their homes.85 Linkletter, Moore, and Godfrey charmed audiences with a "flirtatious sexuality covered over by boyish naiveté," a masculinity modified to include naughtiness, humor, and "those traits traditionally associated with women—'sweetness,' gentleness toward children and animals, deference to others, empathy, and attentive listening."86 Allen Prescott similarly tempered the masculinity of his host persona to best match the comic tone of the program, the generic demands of a household hint show, and the world of daytime in which he labored. His persona, however, was starkly different from that modeled by the charm boys. Full of cynicism, support, and sympathy for women with nary a hint of sexual tension, Prescott's wife saver came across as more of a gay gal pal than a flirt. He won audiences not with an "appealing but low-key sexuality," but with an empathetic sarcasm.87 Although Prescott's persona, as I will discuss, helped him successfully negotiate some boundaries, his close alliance with the marginalized female audiences in the daytime eventually proved problematic.

To manage the gender unease prompted by The Wife Saver's hybridity, Prescott created a loosely autobiographical comic persona—a hapless, inept bachelor who hung out with the girls. As part of an industrial strategy that intensified as Prescott anticipated a jump to prime time in 1942, Prescott "confessed" to a journalist that he was a bachelor and thus, no authority on homemaking:

"I am one of the greatest fakes in the world," announced Allen Prescott . . . "I am a swindle. I don't know a damn thing about kitchens. I'm a bachelor, never eat in, and spend most of my life in restaurants. I couldn't possibly whip up a lemon pie. When somebody asks me how to fry tomatoes, my inclination is to say, 'For God's sake, throw 'em in the pan and fry 'em.' Do you know I once ruined coffee pots from Maine to California by telling women to clean them with lye?" He chuckled. "Some fool woman," he explained, "Told me that and I broadcast it. How would I know? I'm just the household expert."88

In the press, Prescott often narrated "real-life" scenarios that highlighted his incompetence as a household expert. Applying "years of skill and exacting knowledge" to a stuck salt shaker, Prescott's chance meeting with the actor Boris Karloff in a restaurant ended with Prescott dumping salt into Karloff's lap.89 In another scenario, Prescott described a comic evening at the home of an ad executive in which his "helpful hints" angered his hosts and prompted the maid to quit.90 Even though his incompetence violated one of the main generic requirements of daytime homemaking shows, Prescott's persona, a bachelor who caused more domestic chaos than he resolved, was necessary to sustain a masculine authority in the daytime and to distance the real Allen Prescott from his on-air personality. Prescott's domestic naiveté offered listeners a comic character at which women could laugh and one with which women could identify.

To manage the generic unease of this comic figure, Prescott acted as a girl's best friend within the series. Prescott not only shared a nonsexual intimacy with his audiences, but also figuratively crossed the gendered divide.91 When he opened each episode "Hello Girls," Prescott was not only addressing his female listeners, but also imagining himself as one of them.92 This transgressive impulse was clear in a hint on making a frankfurter appetizer so good it would make men think of summer afternoons at a baseball game. This observation gave Prescott an idea:

[W]e ought to get together and think up something that will make men think of mink coats, theater tickets, a ruby or two, and an emerald on odd Wednesdays. Then, of course, we ought to think up something that will make them dream up a way to pay for these. Well, it's worth spending a little time on.93

Although his joke played on the basest of stereotypes, Prescott discursively identified with the women longing for life's luxuries. Colluding with them on air, Prescott created the intimate bond necessary in commercial radio. Prescott's role as a housewife's best girlfriend negotiated the intimate demands of the medium, the comic conceit, the generic demands of a household program, and the gendered environment of daytime.

The wife saver character—a bachelor and gal pal—was a flexible, temporal identity that tried to resolve the tensions that emerged as gender, genre, daytime, and radio interacted in and around the program. Prescott's wife saver, untethered to heterosexual marriage, was a less threatening patriarchal presence for daytime. Yet, as a bachelor, a man not yet married, Prescott still embodied the potential to attract and be attractive to his female listeners, a quality noted in several interviews about the series.94 Acting as "one of the girls," the masculinity of the wife saver was softened to make the intimate moments he shared with his many married listeners less suspect. As a bachelor, a suspect cultural identity that implied homosexuality, Prescott was a suitable companion for America's housewives. Prescott's comic performance of bachelorhood, a figure that distorted generic and ideological expectations, offered additional flexibility. Whatever threatened the generic conventions of daytime homemaking shows or the system of gendered spheres of labor could be played off as a joke. Prescott's comic character allowed the host to embody different positions—for example, an incompetent household expert to assert masculine authority, or a feminized presence to sustain intimacy with female listeners—to negotiate the competing demands of gender ideology and generic conventions. Within the interpretive framework of daytime radio, Prescott's bachelor wife saver recuperated the generic and ideological destabilization of its innovations.

However, such gender flexibility jeopardized the heteronormative ideal assumed for on-air radio personalities. Neither just "one of the girls" nor just "one of the boys," Prescott's persona as the wife saver blurred distinct gender boundaries. Introducing his readers to this "handsome young man," one reporter described how

Mr. Prescott dresses up his household hints with bright chatter. He told me he tries to strike a medium between Arthur Godfrey and Mary Margaret McBride. And for striking such a medium he has the ladies of the land just loving him. They send him apple butter and whisky and homemade cough medicine and knitted socks . . . And, since he's a bachelor, they send him proposals of marriage. He recently got one from a demented lady, written at the sanitarium.95

In this brief account, the reporter offers evidence of Prescott's heterosexual appeal. Yet, at each turn of phrase, the description of Prescott's masculinity is undercut by hints that Prescott's character is not as "straight" as he appears. Prescott may be handsome, but he is fluent in women's chatter, "dress[ing] up" his hints for their enjoyment. He may get marriage proposals, but they are from women in sanitariums. He aspires to the genial masculinity of Arthur Godfrey or the hard-nosed femininity of "first lady of radio" Mary Margaret McBride, and not to the sexual seductiveness of a matinee idol. Prescott's wife saver character not only threatened to erase the boundaries between separate gendered spheres of labor, but also boundaries between straight and queer masculinities.

The discursive rupture caused by Prescott's wife saver persona was noted in a 1941 piece in Radio and Television Mirror. Allen Prescott, observed the reviewer, is "a husky, handsome chap who doesn't fit in at all with one's mental picture of a man who presents household hints on the air."96 After offering evidence of Prescott's heterosexual bona fides—he was a sports star and graduate of a military academy—the reviewer conceded that "even if [Prescott] doesn't look or act the part, he does offer [his female listeners] some interesting and very unusual tips on cooking and home-making on every program."97 The barely concealed homosexual subtext of Prescott's daytime radio performance threatened to erase various boundaries—public/private, men's work/women's work, and homosexual/heterosexual masculinities—upon which daytime was based. Unlike the soft, masculine appeal of the charm boys of radio and early television, Prescott's wife saver persona offered his audiences dark humor, sarcastic asides, and a queered masculinity that did not fit comfortably in the industrial categories in which he labored. The need to alleviate the implicit danger of Prescott's daytime role animated much of the public discourse circulating around the show.

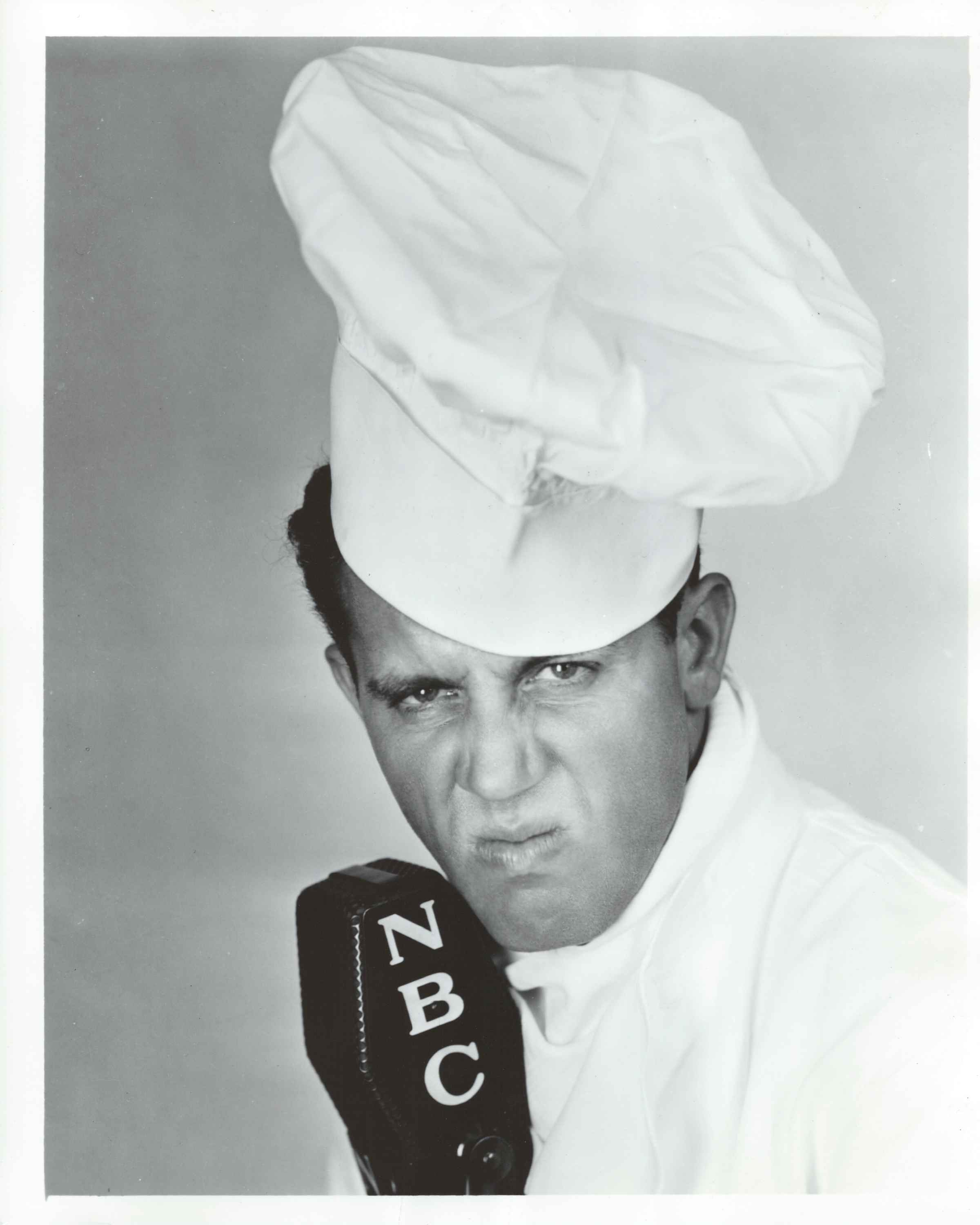

Although the wife saver character allowed Prescott some flexibility to meet the generic and gendered standards of a daytime homemaking program, his persona's elasticity was constrained by the gender demands of the daytime context. Within the homemaking format, the malleable gendered identity offered by Prescott was uncomfortably transgressive. To pull off this comic conceit and meet his generic obligations, Prescott was required to "cross dress," to shift his gendered identity to negotiate the various transgressions triggered by the program's innovations. Several publicity photos visualized Prescott's ambivalence about being a man in a woman's world. Contempt, of his daytime job, of the need to don feminine dress, and of his female audience, was a consistent feature of the publicity photos circulated in the press. One picture featured a close-up of Prescott, dressed as a chef, wrinkling his nose in disgust; in another, an unhappy Prescott, dressed in a frilly apron fit uneasily over his suit, made dinner with one hand while a cigarette dangled from the other.98 (Figure 3) In a hint about nighttime beauty routines, Prescott, dressed in a woman's kerchief and a man's suit, winced as two men slapped cold cream on his face.99 While Prescott was the man on the radio, the creator, writer, and comic talent of the program, one reporter argued, he still played the part of "mother's little helper" in daytime.100 Femininity was a costume mandated by daytime radio, one that Prescott wore awkwardly. These visual depictions of Prescott's discomfort demonstrate both Prescott's use of a queered masculinity to appeal to female listeners and simultaneously its usefulness in allaying wider industry fears about Prescott's sexuality. Crossing from public to private, from masculine to feminine, Prescott's ability "to be his own man" (and to be a woman in daytime radio) was thus restricted.101

To recuperate the gendered rupture of his comic persona, Prescott sought to explain his wife saver persona publicly. As suggested by Margaret McFadden in her analysis of Jack Benny's comic character, The Jack Benny Show represented "authority and masculinity as deriving primarily from a man's economic position, regardless of his other traits."102 Because his bachelor persona was problematic, Prescott and the publicity machine promoting The Wife Saver highlighted the nature of Prescott's work in the program. Consistently in the press, Prescott declared that he was really not a household expert; he just played one on radio. The caption accompanying a photo of Prescott—"Radio Actor"—"Allen Prescott plays the hero in the 'Wife Saver' programs heard on the NBC-WEAF network"—reminded listeners that Prescott's job was to pretend to be a household expert.103 Because he was a comedian, the trade press argued, America's housewives could not take his domestic barbs seriously. For example, next to a photograph of Prescott dressed up like a chef, the caption read,

[F]or more than three years Prescott has played his role of kidding housewives into enjoying household duties and showing them detours around drudgery.104

Through comedy, suggested George Wieda in Broadcasting, women could be taught to focus their efforts in the home:

Prescott's listeners register only one complaint: he makes them go to work. One housewife wrote that after a dissertation he gave on cleaning silver she cancelled all engagements and devoted the day to brightening up her tableware.105

In his redirection of women's laughter into productive labor, Prescott assured the industry of the program's conformity to broadcasting conventions, gendered spheres of work, and strict gender identities.

To explain his decade-long presence in daytime, Prescott characterized his relationship with America's housewives as a marriage of convenience. Though he had other professional aspirations, Prescott was unfortunately wedded to his daytime listeners. One columnist recounted that "every time Allen Prescott, the airways' Wife Saver, tries to get out of the kitchen—and he does, every little while—the girls drag him back."106 Prescott's cycle—trying to leave daytime, America's housewives, and the kitchen behind, but always returning to his girls, The Wife Saver, and the program's $20,000 annual salary—suggested that though Prescott wished to be free of this arrangement, he couldn't give up the financial security his relationship with housewives conferred.107 Here, the pun "the girls drag him back" is instructive. Acknowledging the subversiveness of his daytime "drag" performance, the networks and Prescott took great pains to "normalize" Prescott's relationship with his girls and sidestep the homosexual subtext of his on-air performance. Prescott, resigned to his daytime fate, eventually realized that "'you can't keep kicking Annie out of the house and expect her to keep coming back.'"108 Replicating the structure, if not the emotion, of a heterosexual marriage, Prescott explained both his relationship and his success with his daytime female audience. By referencing his marriage to the nation's housewives, Prescott reframed his drag performance and reaffirmed his straight masculinity in anticipation for a move to evening radio.

Although daytime was the reason for his professional prominence, Allen Prescott paid a price for his association with America's housewives. His professional aspirations, specifically his yearning to be a prime-time comedian, were thwarted by the popularity of and commercial interest in The Wife Saver. Despite intense lobbying by Prescott internally and publicly in the press, NBC was reluctant to give a sponsored daytime host (and confirmed bachelor) a prime-time comedy slot.109 Although pragmatism certainly played a role in keeping Prescott in daytime, Billboard suggested that standardization of the broadcast schedule by 1936 permitted little crossing of the prime time/daytime divide. Billboard reported that radio had come to rely on "standard acts," a personality who had a substantial audience following that could sustain noncommercial programs until sponsorship could be secured, and used Prescott as an example of a reliable radio personality.110 But because of the "peculiar type work" he did in the commercial daytime, Billboard argued, Prescott was not a go-to radio personality.111 Excluded from its list of comedic "standard acts," Billboard classified Prescott, along with The Mystery Chef's John MacPherson and home economist Ida Bailey Allen, as "freak acts."112

Like these other denizens of daytime, Prescott, queered by association, was not a suitable candidate for prime-time stardom. Although NBC did offer him a brief try at a nighttime variety show in 1942, nearly ten years into his run as The Wife Saver, the network offered Prescott more opportunities to broadcast on the periphery of its schedule or in less prestigious prime-time genres.113 In the end, he was neither able to shake the stink of daytime nor elude its gendered constraints. His career, as declared in his 1978 obituary, "Allen Prescott, 74, 'Wife Saver'" was defined by his association with the program.114

Conclusion: "I Hope There's Nothing Burning"

Although much more research is needed to make definitive conclusions about daytime's complicated relationship to comedy, my study of Allen Prescott and the comedy of The Wife Saver suggests some secrets to the series' success on the margins of the broadcast schedule. Prescott's complex negotiation of gender, daytime, and comedy in The Wife Saver required both generic rigidity and gender flexibility—a strong hegemonic generic structure that could serve as a platform for comic transgression and absorb the destabilizing threats of comic asides; and, in the case of a male host, a personality able to move fluidly between different gendered positions to meet generic needs. A specific constellation of characteristics, tenuously balanced against each other, had to be present to manage the difficult and combustible combination of women, daytime, radio, and comedy. To simultaneously attract female listeners and contain the potential volatility of comedy, The Wife Saver wooed female listeners with cynical asides about domestic life and promptly returned them to their daily routine.

To meet the generic conditions of the daytime homemaking program and to assert a public, masculine identity, Prescott shifted between a persona as a hapless, inept bachelor, one of the girls, and a comedian who publicly disdained the very audience he privately entertained. Balancing irreverence with the utmost reverence for women's work in the home, The Wife Saver created a "recipe for laughs" that preserved beliefs about the rhythms of a woman's day, the commercial function of daytime, and the logics of gendered relations of labor and power. Vividly illustrating why there were not more comedy programs on the daytime schedule, a close analysis of the generic features of this hybrid homemaking genre and the gendered performance of host Allen Prescott demonstrates how difficult it was to replicate the recipe offered by The Wife Saver.

Daytime, as an industrial and gendered category, placed constraints on comedy, but not absolute ones. Despite the power of the American broadcasting industry to ghettoize Prescott and The Wife Saver and to develop generic structures, hosts, and a daytime schedule to contain the transgressiveness of comic messages, there were limits to radio's power to regulate the experience of the daytime audience. Only as flexible as rigid gender norms would allow and only as innovative as the commercial structure would permit, radio was restricted in its management of women's consumption of comic messages. If Prescott could be welcomed as "one of the girls," on radio, so too could his domestic cynicism. Thus, while news reports about The Wife Saver reassured readers that, comedy notwithstanding, women would "rush away from the radio to put his household hints into effect" at program's conclusion, the radical nature of the humor in this show—that there was a community of women who needed comic relief from their labor in the home and desired an escape from it—could not be contained.115 The delicate blend of comedy and cleaning required in daytime exposes radio's fraught and fragile relationship with its female listeners, with the gendered division of the broadcast schedule, and with the traditional gender ideology that daytime supported.

In this context, Prescott's concluding catchphrase—"Don't Forget, Mrs. Housewife, I hope that nothing's burning"—suggests that the formula for laughs generated by this homemaking program was far from foolproof.116 While this reminder directed women back to their housework, it also acknowledged that the listener might have been too busy chuckling to care. Thus, despite the careful way that the series was crafted to meet the presumed needs of listeners and advertisers, to negotiate the demands of gender and genre, and to reinscribe gendered relations of labor and power, the danger of comedy in the daytime still simmered. If women laughed during the day, what else, the architects of daytime worried, could boil over?

About the Author

Jennifer Hyland Wang is an independent scholar who received a Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in Media and Cultural Studies. Her research focuses on the relationship between gender and broadcast history, specifically on radio, daytime, and women's work. She is currently working on a manuscript on the interaction of the daytime female audience with the radio and early television industries and an essay on the feminization of podcasting. Her published work on radio, television, and film can be found in Radio Reader, Cinema Journal, and the Velvet Light Trap.

Acknowledgments

I owe profound thanks to the many scholars and colleagues who read drafts of this paper or discussed key issues with me, including Michele Hilmes, Kathy Fuller-Seeley, Bill Kirkpatrick, Cynthia Meyers, Josh Sheppard, Nora Patterson, Brian Fateaux, Kit Hughes, Christopher Cwaaynar, Alexander Russo, and Daniel Wang. I would like to thank Dorinda Hartmann and Karen Fishman for helping me with the research on this paper at the Library of Congress. Last but certainly not the least, I would like to thank Mary Beth Haralovich and Mary Desjardins for giving me this opportunity to develop this conference paper into a full-fledged article and for their careful and thoughtful comments in subsequent revisions.

Endnotes

1 Quoted in George Wieda, "'The Wife Saver': Novel Household Feature," Broadcasting 3:7 (October 1, 1932), 7.

2 Although this story of the show's origin is the most often repeated, there are competing accounts of the series' start. See Earl Wilson, "His Ignorance Nets Him $20,000 a Year," New York Post, March 6, 1942, Box 4, Allen Prescott Collection, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress (hereafter Prescott); and Edmund Leamy, "Was He Surprised-!," New York World Telegram, May 29, 1945, Box 4, Prescott. In the fan magazine Radio Mirror (eventually renamed Radio and Television Mirror), there are two accounts that suggest the start of the series was much less dramatic. The account suggests that Prescott added household hints to his news commentary on slow news days to fill up airtime, and that audiences enjoyed the household hints more than his news commentary. See "On the Air Today," Radio and Television Mirror, May 1941, 44; and Margaret Simpson, "Livesavers For Wives," Radio Mirror, November 1937, 54. The significant difference in these stories is that later press accounts insist that Prescott was forced to host this program, and in the fan press, Prescott develops the program on his own in response to audience interest. The circulation of this story in 1942 may suggest an intentional strategy on the part of Prescott to distance himself from the program he created and the daytime female audience that he served in order to position himself professionally as a candidate for prime-time comedy work.

3 Wilson, "His Ignorance Nets Him $20,000 a Year," Box 4, Prescott.

4 Ibid.

5 Wieda, "'The Wife-Saver,'" 7.

6 See, for example, "Who'll Save the Wife Saver?," Radio Mirror, July 1942, 43, "Housewives . . . His Domestic Hints," n.d., Box 4, Prescott; and Leamy, "Was He Surprised-!"

7 Wieda, "'The Wife-Saver,'" 7.

8 Joe Hoffman, "Music-Radio: Air Briefs," Billboard, 44.38, September 17, 1932, 17.

9 Between 1941 and 1943, the program, renamed Prescott Presents, aired for a half hour. See Allen Prescott Collection Finding Aid, 3, Prescott. See John Dunning, On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1998), 721; Harrison Summers, A Thirty-Year History of Programs Carried on National Radio Networks in the United States, 1926-1956 (New York: Arno Press and New York Times, 1971), 35, 48, 56, 64, 80, 96, 104; and Resumé for Allen Prescott, Box 1, Folder 9, Prescott. Over the years, the program was sponsored by Fels-Naptha and the Manhattan Soap Company. See "New Biz, Renewals," Billboard 46.35, September 1, 1934, 8; "New Biz, Renewals; WNEW a Sensation," Billboard, February 24, 1934, 46; and "Network Accounts," Broadcasting 12.1, January 1, 1937, 60. The show's placement on the Blue Network also reveals NBC's belief in the show's potential, but not necessarily evidence of the show's strength.

10 The Wife Saver was revived for thirty-nine weeks on the New York station WNEW in 1944; Mutual brieUniv. of fly picked up the radio show in 1954; and it was reported that somewhere between 150 and 200 episodes of the radio program were available for sale to local stations and regional networks. See "Playback," NBC Radio-Recording Division advertisement, Radio Daily, May 23, 1946, 4, Box 1, Folder 9, Prescott; "P&G Test Wife Saver," Billboard 50.8, February 19, 1938, 10; "The Wife Saver," Variety 192, September 23, 1953, 3; Resumé of Allen Prescott, Prescott; and "Sponsors," Broadcasting 32.21, May 26, 1947, 62. The hints collected from female letter writers filled two books, The Wife-Saver's Candy Recipes and Aunt Harriet's Household Hints.

11 See "Soap Operas On Decline," Variety, November 10, 1943, 47; "CAB Probe Points up Stronger Pull of Variety Shows," Variety, October 20, 1943, 35; "CBS' Matinee Facelifting," Variety, September 22, 1943, 31; "Daytimers Feel Retrenchments," Variety, December 20, 1944, 21; and "Non-Soapers Move in on Daytime Web Skeds But Weepers Still Rule," Variety, December 13, 1944, 20.

12 This dynamic combination—daytime, women, comedy, and radio—is woefully underresearched in contemporary scholarship. For recent work on gender, radio, and daytime radio, see Michele Hilmes, Radio Voices: American Broadcasting, 1922-1952 (Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 1997); Jennifer Hyland Wang, "Convenient Fictions: The Construction of the Daytime Audience, 1922-1960," (PhD diss, Univ. of Wisconsin-Madison, 2006); Kate Lacey, Feminine Frequencies: Gender, German Radio, and the Public Sphere, 1923-1945 (Ann Arbor: Univ. of Michigan Press, 1996); and Jason Loviglio, Radio's Intimate Public: Network Broadcasting and Mass-Mediated Democracy (Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 2005). Although there has been a recent renaissance of studies on prime-time radio comedies by Kathy Fuller-Seeley and David Weinstein, scholarly analyses of daytime comedy have been virtually nonexistent. More recent revisionist work on prime-time radio comedy that focuses on the cultural and industrial work of prime-time comedy has been produced by Kathy Fuller-Seeley, "Reinventing Jack Benny: Developing the Character-Focused 'Comedy Situation' for Radio" (paper presented at annual meeting of Society of Cinema and Media Studies, Boston, March 21-25, 2012); David Weinstein, "The 'Apostle of Pep' Tackles the Airwaves: Eddie Cantor and Broadway Style in 1930s Radio" (paper presented at annual meeting of Society of Cinema and Media Studies, Boston, March 21-25 2012); and Margaret T. McFadden, "'America's Boy Friend Who Can't Get a Date': Gender, Race, and the Cultural Work of the Jack Benny Program, 1932-1946," Journal of American History 80.1 (June 1993), 113-34. The only direct discussion of the relationship of daytime and comedy is Jennifer Hyland Wang, "No Jokes: The Marginalization of Comedy in Early Daytime Radio" (paper presented at annual meeting of Society of Cinema and Media Studies, Boston, March 21-25, 2012).

13 Arthur Wertheim, Radio Comedy (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1979), 4. Even if they were so inclined, some vaudeville showmen such as E. F. Albee often banned their performers from radio.

14 "Why It Is Difficult to Be Funny over the Radio," Radio Broadcast 9, June 1926, 133.

15 "Radio," New Outlook 165, March 1935, 58.

16 Milton MacKaye, "The Whiskers On The Wisecrack," The Saturday Evening Post 208, August 17, 1935, 12.

17 Orrin E. Dunlap Jr., "Radio Generalship," New York Times, October 22, 1933, 11. See also Wertheim, Radio Comedy, 91.

18 Genevieve Cain, "Flogging the Ether," American Mercury 17, August 1929, 454. Similar observations were offered in Peter Dixon, Radio Writing (New York: Century, 1931), ix.

19 Dixon, Radio Writing, ix; and "Why It Is Difficult to Be Funny over the Radio," 133.

20 For an in-depth discussion of the controversy over Mae West's performance on The Chase and Sanborn Hour, see Matthew Murray, "Mae West and the Limits of Radio Censorship," Colby Quarterly 36.4 (December 2000): 261-72; or Matthew Murray, "Broadcast Content Regulation and Cultural Limits, 1920-1962" (PhD diss, Univ. of Wisconsin-Madison, 1997).

21 Shawn Van Cour discusses radio's tendency to adapt existing cultural forms and mesh those formats with the mass audience and aural aesthetics of radio. See Shawn Van Cour, "The Sounds of 'Radio': Aesthetic Formations of 1920s American Broadcasting" (PhD diss, Univ. of Wisconsin-Madison, 2008), 203. Early broadcasters found in vaudeville a rich source for the development of radio comedy. The vaudeville bill of fare, featuring a seamless flow from one act to another, was a model for network schedule development. Vaudeville's consistent and repetitive comedy routines fit the production cycle of network radio and appealed to both local and national audiences. Vaudeville's collapse in the early years of the Great Depression presented eager national sponsors with an available pool of seasoned, New York-based comedic talent.

22 Wertheim, Radio Comedy, 5.

23 Wertheim, Radio Comedy, 7.

24 NBC's The Cuckoo Hour starring Raymond Knight burlesqued radio by establishing an imaginary station (Station KUKU) and airing parodies of the different radio genres, such as bedtime stories or hints to housewives, on contemporary schedules. CBS's The Nit-Wits made fun of popular radio entertainers. Snoop and Peep satirized mystery thrillers. And Sisters of the Skillet (also known as the Quality Twins) concocted farcical solutions to real household problems to satirize the household hints shows on during the daytime. See Dixon, Radio Writing, 135-38.

25 Summers, A Thirty-Year History of Programs, 31; and Hilmes, Radio Voices, 183-212.

26 Wertheim, Radio Comedy, 87-88.

27 Hilmes, Radio Voices, 183-88.

28 See Katharine Seymour and John T. W. Martin, Practical Radio Writing: The Technique of Writing for Broadcasting Simply and Thoroughly Explained (New York: Longmans, Green, 1938), 142-43.

29 Telegram from E.P.H. James to Wm. B. Remington Inc., n.d., Box 4, Folder 121, E.P.H. James Collection, Wisconsin Center For Film and Theater Research, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison. See also Erik Barnouw, Handbook of Radio Writing (Boston: D. C. Heath, 1949), 188.

30 Lawrence Holcomb, "The Foolproof Duo: Daytime and Women," Broadcasting, July 1, 1937, 29.

31 See Summers, A Thirty-Year History of Programs.

32 Ralph Rogers, Dos and Don'ts of Radio Writing (Boston: Associated Radio Writers, 1937), 32-33.

33 "Trend Is to Novelty," Variety, August 26, 1936, 47.

34 See "Radio's Script Act Cycle," Variety, May 10, 1932, 55; "Major Networks Nearly Sold up on Evening Time, 'Cept Saturdays," Variety, October 11, 1932, 57; and Reuben R. Kaufman, "Audience is Determined by When, What and Where You Broadcast," Broadcast Advertising, April 1931, 17.

35 Dunning, On the Air, 114, 115, and 281.

36 Alexander Russo, "Tick Tock Goes the Musical Clock: Time Discipline and Early Morning Radio Programs," in Radio's New Wave: Global Sound in the Digital Era, edited by Jason Loviglio and Michele Hilmes (New York: Routledge, 2013), 194-208.

37 Lois Rudnick, "Women's Humor and American Culture," review of A Very Serious Thing: Women's Humor and American Culture, by Nancy A. Walker, and Redressing the Balance: American Women's Literary Humor from Colonial Times to the Present, by Nancy Walker and Zita Dresner, American Quarterly 42:4 (December 1990), 671.

38 See Wang, "Convenient Fictions," 110-15.

39 Ben Gross, "Listening In," New York News, September 15, 1938, Box 4, Prescott.

40 Wieda, "'The Wife-Saver,'" 7.

41 "The Kitchen," Box 1, Folder 10, Prescott; and Wife Saver Script, December 20, 1938, 1-2, Box 1, Folder 1, Prescott. For information on how radio homemaking programs incorporated the language of the marketplace and science into their discussions of home management, see Maggie Andrews, Domesticating the Airwaves: Broadcasting, Domesticity, and Femininity (London: Continuum, 2012) and Lacey, Feminine Frequencies, 37-40.

42 The Wife Saver was one of the top five sustaining programs in attracting mail, often averaging 500 letters a week in 1936. See "Quirks of Listeners," New York Times, May 31, 1936, 10; and "Allen Prescott, 74, the 'Wife-Saver,'" New York Times, January 29, 1978, 42.

43 The Wife Saver Script, April 8, 1940, 5, Box 1, Folder 1, Prescott.

44 These claims appeared in Wieda, "'The Wife-Saver,'" 7, and "Just In Time," Broadcasting, 34:19, May 10, 1948, 76. The discussion of Prescott as a saver of wives is present in clippings such as "Manhattan…:He Saves Wives," n.d., Box 4, Prescott.

45 Wieda, "'The Wife-Saver,'" 7. There are no existing audio copies of The Wife Saver during its original run and only a few postwar examples of The Wife Saver or similar programs Prescott hosted, such as Time Out With Allen Prescott. The few existing copies of The Wife Saver can be found at the Library of Congress where Allen Prescott's papers are housed.

46 Ben Gross, "Listening In," New York Daily News, July 8, 1938, Box 1, Folder 12, Prescott; Leamy, "Was He Surprised-!"; Prescott, "NBC Artists Service Memo," Box 4, Prescott,; and "Television Review," Billboard, July 29, 1939, Box 4, Prescott.

47 Audio Recording RXA 2480, n.d., Prescott.

48 "1949-1950 Women's Programs," Radio Daily, August 25, 1949, 136; Variety, October 18, 1939, Box 4, Prescott; and quoted in "Allen Prescott, 74, the 'Wife-Saver,'" 42 .

49 "Allen Prescott, 74, the 'Wife-Saver,'" 42.

50 Orrin E. Dunlap Jr., "Furiously Proceeds Radio's Gag Hunt," New York Times, August 26, 1934, 15.

51 "Experimental—(Wifesaver No. 2)," A.E. Staley Mfg. Company commercial, n.d., 1, Box 1, Folder 4, Prescott. This particular joke was embedded in an undated, five-minute version of The Wife Saver to promote A.E. Staley products.

52 Patricia Mellencamp, "Situation Comedy, Feminism, and Freud: Discourses of Gracie and Lucy," Studies in Entertainment: Critical Approaches to Mass Culture, Tania Modleski, ed. (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1986), 92-94.

53 Joanne Gilbert, "Performing Marginality: Comedy, Identity, and Cultural Critique," Text and Performance Quarterly 17 (1997), 328.

54 Nancy Walker, "Humor and Gender Roles: The 'Funny' Feminism of the Post-World War II Suburbs," American Quarterly 37.1 (Spring 1985), 102.

55 Quoted in Mellencamp, "Situation Comedy, Feminism, and Freud," 93.