Volume 2 Issue 1 (2009) DOI:10.1349/PS1.1938-6060.A.340

Virtual KinoEye: Kinetic Camera, Machinima,

and Virtual

Subjectivity in Second Life

Lori Landay

I am kino-eye, I am a mechanical eye. I, a machine, show you the world as only I can see it. . . . free of the limits of time and space, I put together any given points in the universe . . . . My path leads to the creation of a fresh perception of the world.1

With this invocation of "kino-eye", Soviet filmmaker Dziga Vertov imagined the possibilities of cinema, some of which he was able to actualize in his film Man with a Movie Camera (1929), but his words have fresh meaning in light of the new ways of seeing and being in virtual worlds. In virtual worlds like Second Life, the kinetic camera freed from the limitations of the human body is realized in a manner beyond even Vertov's wildest imaginings. This creates great possibilities for machinima—movies made within the 3-D graphical environment of a video game or virtual world—but also the 3-D synthetic camera function in Second Life can be used as a way of experiencing the virtual world that creates a new kind of subjectivity, constructed through the point of view of a virtual kino-eye.

Second Life is a virtual world owned by a company called Linden Lab, in which all content is created by the "residents" who are represented by avatars. (For a 3-minute overview of Second Life, see my Machinima: What is Second Life?.) It is of interest to people in the media studies fields for a range of reasons, including the possibilities for making and sharing machinima within it, its potential as a form of interactive and immersive new media, and its prospects for education, art, music, and social media. In particular, if we think of a virtual world as a new form of participatory media in which what I am terming the "virtual kino-eye" is not only a tool for digital video making, but also the way in which one experiences the virtual world and constructs subjectivity, it becomes very interesting to those interested in the continuum of theoretical issues from spectatorship to participatory media.

MACHINIMA & VIRTUAL KINO-EYE

Machinima, digital video captured in a virtual world like Second Life, is a kind of animation. The word "machinima" combines cinema and machine, and was first used in 2000 to describe the video capture of realtime 3d action in a virtual environment that originated with first-person-shooter video games like Doom and Quake in the 1990s. What had origins with hackers in the demo scene in the late 1970s and into the 80s and went more mainstream as a way of documenting how fast someone could finish a level quickly evolved into a medium for storytelling, and the game environment became the set for virtual filmmaking.2 For people who play games, machinima is a way to participate in those worlds in an even more active way, going far beyond the experience of playing to becoming a creator within that framework, and often subverting it. From its very first episode (see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9BAM9fgV-ts and, be warned, there is strong language), the hilarious Red vs Blue machinima questions the very basis of the game Halo within which it is made. In an insightful essay, Robert Jones connects the kind of interaction that machinimists have within games to Huizinga's "magic circle" of game-playing and game design scholars Salen and Zimmerman's concept of "transformative play," extending ideas raised by Henry Jenkins and others about fan culture, transmedia, and participatory media into the arena of interactive forms of media like games in his consideration of whether the professionalization of machinima-making means the loss of the inside-out gamer approach as the emphasis switches to storytelling instead of transformative play. I would like to suggest a third alternative to Jones' dichotomy, that represented by virtual subjectivity constructed through kino-eye; it is possible that in making machinima within a virtual world, storytelling is inseparable from transformative play because the very act of seeing as and with a camera in the virtual world can be transformative.

The machinima I make is "filmed," or more accurately, captured, in Second Life, a virtual world created entirely by the "residents." It is not a game--although people can and do play games within it, and perhaps here a definition of a virtual world will help: "A synchronous, persistent network of people, represented as avatars, facilitated by networked computers."3 In Second Life, the possibilities for machinima are dazzling and almost limitless. Because people can build whatever environment they want, either themselves or by hiring talented artists, machinima can be made on almost any set someone can imagine. I set up shots on my land or in spaces owned by my friends, often building sets or adding props and set design, creating animations for avatars to perform specific actions, depending on the project. There are limits as to what avatars can do in terms of acting, but that is bound to develop quickly, once there is a greater range of facial expressions.4 Despite the limitations, in a sense, the machinamist has the most powerful crane/dolly/zoom/aerial shot package one can imagine, and the machinima I have made that accompany this essay try to demonstrate that.5

One could even see the kinetic quality of the synthetic camera function in Second Life as an answer to Vertov's dream of the kino-eye's exhilarating separation from the limitations of the body. In his writing, Vertov imagines the "I" of the kino-eye, bragging and delighting in its joyous nimble freedom:

Now and forever, I free myself from human immobility, I am in constant motion, I draw near, then away from objects, I crawl under, I climb onto them. I move apace with the muzzle of a galloping horse, I pluge full speed into a crowd, I outstrip running soldiers, I fall on my back, I ascend with an airplane, I plunge and soar together with plunging and soaring bodies. Now I, a camera, fling myself along their resultant, maneuvering in the the chaos of movement, recording movement, starting with movements composed of the most complex combination.

In his film, Man With a Movie Camera, as many film historians have noted, Vertov employs a dazzling array of film techniques that do indeed demonstrate the possibilities of camera and montage to create a new experience of perspective, subjectivity, mobility, and modernity. Lev Manovich connects Vertov's enthusiastic use of everything available to him to a larger argument about database and narrative, and ultimately navigable virtual space. Manovich considers why Vertov's film is more than just a catalogue of effects, why "in the hands of Vertov, they acquire meaning"

Because in Vertov's film they are motivated by a particular argument, which is that the new techniques of obtaining images and manipulating them, summed up by Vertov in his term "kino-eye," can be used to decode the world. As the film progresses, straight footage gives way to manipulated footage; newer techniques appear one after another, reaching a roller-coaster intensity by the film's end—a true orgy of cinematography. It is as though Vertov restages his discovery of the kino-eye for us, and along with him, we gradually realize the full range of possibilities offered by the camera. Vertov's goal is to seduce us into his way of seeing and thinking, to make us share his excitement, as he discovers a new language for film. This gradual process of discovery is film's main narrative, and it is told through a catalog of discoveries. Thus is the hands of Vertov, the database, this normally static and "objective" form, becomes dynamic and subjective. More important, Vertov is able to achieve something that new media designers and artists still have yet to learn—how to merge database and narrative into a new form. (243)

In Manovich's reading of Man with a Movie Camera, we learn to see with the kino-eye because Vertov models it for us, and in so doing, shows us a new way of seeing information (the database) because we move through it. Later Manovich concludes his discussion of the forms of database and navigable virtual space by returning to Vertov because Vertov "wanted to overcome the limits of human vision and human movement through space to arrive at more efficient means of data access. . . . Thus Vertov stands halfway between Baudelaire's flâneur and today's computer user: No longer just a pedestrian walking down a street, but not yet [William] Gibson's data cowboy who zooms through pure data armed with data-mining algorithms" (275, emphasis in original).

In my argument, Vertov's kino-eye is made manifest as a metaphor in Second Life. In the interface of the virtual world of Second Life, the spectator-gamer, through his or her avatar, does not leap to the position of the data cowboy exactly, but employs the virtual kino-eye as an eye, and as a camera. The virtual kino-eye, as Vertov so enthusiastically meant it, as a new way of seeing, of creating perspective, of experience, is made possible by the technology of the synthetic camera that moves along the x, y, and z axes within the virtual space, remote from both the physical and virtual bodies of its operator, yet closely, intimately connected to his or her perspective. The kino-eye is how virtual subjectivity is constituted in a virtual world, and is the lens through which experiences like telepresence, avatar identity, building objects, places, or art in the virtual world, and social interactions occur. For the machinimatographer, using the kino-eye, the virtual world is his or her location, set design, lighting, and camera combined, and the only limits are of the imagination.

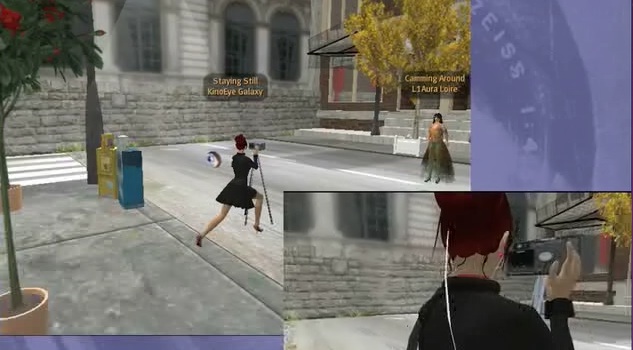

Figure 1: L1's scripted eye object gazes back at the

camera.

Screen shot from Second

Life.

In another sense, though, and this is really the essence of this argument here, it is through this kinetic camera, this virtual kino-eye, that virtual subjectivity is created, and this is how we experience a virtual world in which everything is mutable and fleeting. The digital nature of the virtual world is mutable—that is one of its appeals, of course, that it, one's avatar, one's land, can be so easily bent to the will, customized and constantly evolved, but it means that nothing is ever the same for long. With so much mutability, what would it mean to last? When our very point of view is so unmoored physically, no longer rooted in the body, but free to range far from the avatar, zoom out into space, or in on a leaf, where is the center? Where is home? What is self? It is no wonder that impermanence, ephemerality, and transformation are common themes in virtual art.

How these philosophical questions arise from the practices of using the camera function are part of the fascination of the virtual world for me; metaphors can easily be made manifest, and then interacted with, played with. For example, I made a kino-eye object in Second Life to show where my camera camera position is, or where I am looking as I "cam around," so I could illustrate how virtual subjectivity can be created discursively through the literal and metaphorical point of view of the kinetic inworld camera in one of my early machinimas, "Avatar with a Kino-Eye." [See Machinima: "Avatar With a Kino Eye"].

The concept of the virtual kino-eye made manifest in the object of the kino-eye is informed, for me, as its creator and as I interact with it in the virtual world, by theories of perception, spectatorship and the gaze developed by scholars from Hugo Mustenberg, Christian Metz, and Anne Friedberg to Vivian Sobchack, and particularly Francesco Casetti's Inside the Gaze: The Fiction Film and Its Spectator. It is beyond the scope of this piece to explore this subject fully, but one aspect of Casetti's argument delineates the taboo against the "direct look into the camera and other forms of interpellation" (25), which he defines as the "recognition by the film of someone outside the text to whom the film makes a direct appeal" (138). The default cam position of Second Life is behind the avatar's head; you can choose other spectator positions, including a first-person point of view through the avatar's eyes.

Akin to and more than Anne Friedberg's "mobilized virtual gaze . . . in an imaginary flanerie through an imaginary elsewhere and elsewhen" (Window Shopping, 2), the kinetic possibilities of the virtual kino-eye zoom, fly, race, spin, dance along with Vertov's most utopian hopes for cinema and the new world it would create. My experience making and interacting with the object of the kino-eye illustrates how the virtual kino-eye is not only a tool with which to make machinima, but also a practice through which subjectivity can be constructed in a virtual world. It can be seen as a parable of how kinetic, "alive," and social seeing and creating can be in a virtual world. The object itself plays off of a Magritte image from The False Mirror (1928) to refer to Magritte's visual questioning of subjectivity, mimesis, and spectatorship. The eye uses a programming language to control it with a script written in Linden Scripting Language (LSL), which is how objects and avatars are made to do things in SL, from doors swinging open when clicked on them, to particles spewing from an object in a certain color and pattern, to triggering an animation in a pose ball, or even objects that interact with the SL "wind" or other aspects of the physics engine. Writing the script so the object would follow the camera position was too advanced for a beginning scripter like me, so I asked the teacher of the scripting classes I was taking, Simon Kline, for help. When I dropped his script into my eye object, it worked, and I was thrilled. Later, when I logged back in, I started to cam around as usual. Something flitted by in my peripheral vision on my screen. Then again. I finally caught sight of it, and realized it was my kino-eye, and that I didn't know how to stop it once I had started it. I sent my teacher a message asking for advice, and forgot about it, until I logged in again to be surprised by the eye, still there.

The idea of an object that was not under my control was funny, entertaining to move by manipulating my camera, and giving me good ideas for stories for machinima. My gaze, long a fascination of course, was literally a toy, all the better for being a tricky one. I showed it to friends, asked them to "catch it." When I sent my teacher Simon a message, I didn't use L1's account, but the alternate avatar I use to shoot machinima, who I named Kino-Eye. "This is the eye. I am on the loose. L1 cannot control me!" Hilarious stuff, messages back and forth. He gave me a new script with a command in it for "desist," and now I can start and stop it as I wish, but the ludic possibilities of the virtual world revealed themselves to me as I was involved in the trouble-shooting of the eye-object in a way that dealing with a digital camera or Final Cut Pro glitch has never done. It made me more creative. I shot some footage of the kino-eye, messing around with different settings, first as a welcome pet/friend and then as a pest who will not go away. I also shot some footage for a fairy tale machinima, about Little Red L1, who skips home with a basket of scripts she "borrows" from her teacher that she doesn't understand and unleashes all kinds of sorcerer's apprentice havoc. I use the script in other objects, including an art deco camera plane the designer Alexith Destiny built for me that I use in inworld lectures to fly over the audience's heads, and I have used the kino-eye in video podcasts critiquing virtual art for the Brooklyn Is Watching project for added visual effect. Playing with the scripted eye objects, "acting" with them, making this particular kind of animation reminded me of the stop-motion animation of the film camera in Vertov's Man with a Movie Camera, and I try to emulate the playful tone the animated camera embodies. As much as his use of film techniques and his demonstration of the kino-eye, that ludic sensibility (which also informs the serious play so central to gaming and understanding how the various levels of being both in and outside the 3-d environment intertwine) is one of Vertov's major contribution to our ongoing exploration of new ways of seeing and being, and how they are connected. My experience in learning enough about how a scripted object like my kino-eye works, which took the form of play, took the step that Manovich lauds Vertov for, and attempts to "merge database and narrative into a new form," (243) the active construction of virtual subjectivity through the kinetic virtual kino-eye.

Figure 2: Shots from machinima --

Little Red L1 skips home,

unaware of what follows her.

Although Vertov did not see Second Life, it was in Second Life that I heard French filmmaker Chris Marker say through his avatar "Vertov was my teacher." In many ways, it is not surprising that filmmaker Chris Marker, now 88, would make his way into Second Life to extend some of his ideas about presence, time, persona, memory, and permanence (and their opposites) that Erika Balsom discussed in her essay on Marker's CD-ROM Immemory in a previous issue of e-Media Studies. Through his participation in the Chris Marker museum http://slurl.com/secondlife/Ouvroir/186/66/40) , and also in Fiteiro Cultural at Casa Millagrosa http://slurl.com/secondlife/Fiteiro%20Cultural/60/80/26 a project in which I am also a contributing artist), Marker continues to take image-making and story-telling into new directions with the newest forms of media.

Figure 3: L1 at the Chris Marker Museum

VIRTUAL SUBJECTIVITY

I have suggested that the virtual kino-eye is not only a tool for machinima-making, but a significant way in which one "sees," in all senses of the word, in a virtual world—virtual subjectivity. Beyond using a virtual world or game platform as sets for machinima or to stage performances, the kinetic camera possibilities of the virtual kino-eye are both the interface's "eyes" through which the participant sees and experiences the virtual world and, more significantly for thinking through the ramifications of virtual worlds, how subjectivity is constructed.

The main question here is: what does it mean to say "I" in a virtual world? What does it mean to have a first-person experience of feeling, perceiving, understanding, learning, desiring, being repulsed by, and making meaning in a virtual world? What does it mean to be in a context in which identity can be so self-consciously shaped and refined?

Subjectivity can be defined as the experience of the "I," or, as Raymond Williams' phrase, as "structures of feeling." It encompasses a person's feelings, thoughts, and perceptions; it emphasizes their individual encodings and decodings of their environment, social interactions, and experiences. The term comes from the French verb assujettir, which has a double meaning of both to produce subjectivity and also to make subject. It is both creative and restrictive, and as the concept has taken root in different discourses within the social sciences and the humanities, subjectivity has become like the ball in a tennis match between these two sides of the same coin, to mix metaphors freely. The way I am using subjectivity explores a dialectical relationship between these two poles, and includes ideas about identity, individuality, a person's sense of self and how they make meaning, agency, and consciousness and emphasizes perceptions, desires and interpretations. That emphasis on internal reality means that the boundary between the self and the world is blurred, and is constantly renegotiated.

So, with that I mind, let's turn to thinking about subjectivity in the virtual world of Second Life. If subjectivity is the first-person experience of the "I," shaped by both individual psychological experiences and wider cultural forces, and it is intersubjective—created socially—then the people behind the avatars certainly bring their actual world subjectivities in here. However, once inworld, instead of having a body through which to experience the world—and as my theoretical orientation tends towards phenomenology, I think this is important—we have an avatar and visual and sound input that are not necessarily connected to that avatar's position. There are "mirror neurons"6 in the brain that respond to what the avatar does, but it is different than direct sensory input. Therefore, the already blurry line between the self and the world is completely smudged in virtual subjectivity.

Throughout the rise of visual culture, physical point of view and subjectivity have been connected. To some extent, all visual representation explores this, and as each new visual medium arises, that relationship is recreated and extended. In silent film, the development of continuity editing between expressive camera shots created a narrative-based, emotionally grounded point of view based on a fusion of physical, intellectual, and emotional perspectives. As scholars like Anne Friedberg, Guiliana Bruno, and others have explored, the cinematic gaze is connected to and informs other cultural practices, like consumerism, medical discourses, or nationalism. Sound, color, digital effects, and other technological developments in film and then television reinforce and deepen this, but nothing is as significant as that leap initial to the film spectator.

Until, perhaps, now, with the new spectatorship/participatory gaze with the immersive and interactive virtual world. Specifically, because of the way the viewing position is not by default first-person, in a virtual world, the viewer position is both immersive and detached, both connected intimately to our experience of the avatar—but also strangely outside of him, her, or it. Instead of an "I," inworld we have an I/Eye through which we create virtual subjectivity.

My definition of "virtual subjectivity" is: a mode of first-person experience in a virtual world that is founded on a fusion of visual and metaphoric point of view, shaped through "self-design" of the avatar and environment, reinforced and extended through social interaction, known through the avatar body's actions and movements in virtual space and place, and enacted through virtual agency. Part of virtual subjectivity is the extent to which the mind/body connection translates inworld experiences into embodied sensations that feel "real." To sum up, there are five major factors that contribute to virtual subjectivity:

1) virtual point of view

2) virtual self-design

3) virtual social relationships

4) virtual topophilia and

5) virtual agency

VIRTUAL POINT OF VIEW

Figure 4: Virtual POV -- The "eye" is also the

"I," but who knows if two people sharing the same virtual space are

seeing the same thing?

(Screen

shots of Second Life by Lori Landay)

In a film, the spectator sees each shot from the physical point of view of the camera chosen by the director and the editor. This is cinematic perspective, and is mostly in the third person, although of course there is a powerful component of subjective emotional looking in the cinematic gaze and occasionally, there is spectacularly good use of the first-person p.o.v. (think of the steadicam shot in Goodfellas through Henry Hill's eyes as he introduces us to some of the people in the bar). In the virtual world of Second Life, however, the participant's default looking position is behind the avatar's head, and follows the avatar, but it is not limited to that position. There are other possibilities—the first-person mouse-look which mimics human sight and is locked to the avatar's physical eye position, and a cam view that is unconnected to the avatar's body and can zoom in and out, go around corners, and range far and wide. (See Machinima: Cam Positions)

There are various ramifications to the possibilities of the cam in Second Life. In a conversation, the artist DC Spensley, who is Dancoyote Antonelli in Second Life, articulated some of those ramifications this way:

Radio is to TV like TV is to virtual worlds. This is a real earth shaker, world changer in terms of the focus of the viewer. In a TV or single perspective communal cinema situation, the view is one way and from only one perspective, the director of the content dictates what reality is and you consume that perspective passively. End of story. There is no talk back, nor ability to change your view of the subject, peek back stage or interact. . . . .

Virtual worlds are individual, configurable experiences that empower a viewer to establish any POV they can imagine. Instead of passive entertainment, the burden is now on the viewer to participate in the creation of their own experience on a very basic level.

Spensley, who produces, choreographs, and directs live "SkyDancer" performances in SL, with some seats that guide the spectator's p.o.v. and some that don't, makes the key point that in a virtual world, there has to be active viewing. The resident, or gamer, or participant makes a choice, even if it is to use the default behind the avatar's head most of the time. As one clicks through different animations, pose balls, rides in vehicles, learns to manipulate objects, changing visual point of view becomes as much a part of moving through the virtual world as walking, flying or teleporting. Some Second life theater performances manipulate the viewers camera positions as if it were a film; the virtual adaptation of Fritz Lang's 1927 silent film Metropolis was uncanny, both in its faithfulness to the silent film, and in being able to cam around in the 3-d sets (slide show of the performance) here). When building inworld, the cam is essential. For an excellent machinima tutorial on camera skills by NSS, including my favorite, how to break and enter, see: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2LMcryDCIYk .

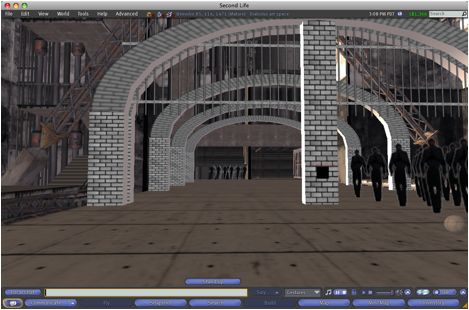

Figure 5: Screen shot of Metropolis performance in Second Life

The various points of view that the participant in a virtual world chooses, whether physical (avatar default, mouselook, camming around, as shown in the machinima) or metaphoric (exploring a different identity through anonymity, role-play, alts, gender-switching, being non-human) can be both tools for machinima--for digital storytelling—or for storytelling and serious play within the virtual world.

Moreover, because in Second Life a person can choose what time of day, lighting conditions, and levels of graphics settings, as well as the camera position, although you might be next to an another avatar, there is no way of knowing what that person is seeing. There is not the same level of shared physical reality as in the actual world, even though people participate in constructing reality for and with each other in those moments when they do share virtual space. Further, what an avatar appears to be doing, or looking at, may not be what the person behind the avatar is doing; within the virtual world, the avatar could be carrying on various Instant message conversations with avatars who are not present in the same virtual space, or could be searching through their inventory, or buying something from the Linden Labs-owned website Xstreet https://www.xstreetsl.com/, or working in a program like Photoshop on something they will upload into Second Life that will become part of the virtual world, or simply away from the computer (afk) entirely. The virtual world is all illusion, and what an avatar seems to be doing is part of that; creating virtual subjectivity means a new kind of social construction of reality based on an even more radically interpretative framework of assumptions, rife with new social faux pas, misunderstandings, and humor.

Figure 6: Choosing the sunrise setting in Second Life at Fiteiro Cultural at Casa Millagrosa. L1's installation in the background, right.

SELF-DESIGN

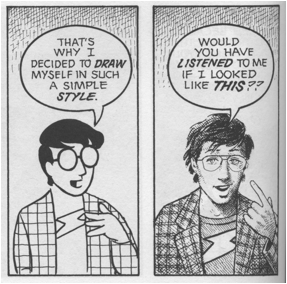

Actual world subjectivity encompasses our experience of our bodies, gender, race, sexuality, age, appearance, and how we fit into cultural ideals of beauty. In a virtual world, however, there are hardly any limits on these aspects of appearance and visual markers of identity. In this image, you can see my experiment in what anthropologist Jason Pine calls "self-design," my modification of my avatar over time; most recently, my avatar is a centaur, which can be seen in Figure 6. I think of the avatar on a continuum of realism and abstraction, in the way that Scott McCloud discusses his choice of self-representation in Understanding Comics:

Figure 7: McCloud suggests the cartoon increases identification because of its simplicity. Scott McCloud, Undertsanding Comics, p. 36.

In the excellent video "An Emergent Second Life,"7 Pine discusses his concept of self-design of the avatar and the environment with various SL participants. Hearing and seeing people talk about their relationship to their avatars, and the choices they made, raise so many questions. Is it an extension of the self-aestheticizing practices glorified in celebrity culture and beyond in postmodern culture? Or is it something else? What does it suggest that avatars are so idealized, so much like the images seen in advertising and the movies? That "skins" are the inworld items people are willing to pay the most for, relative to other virtual goods and services? Why be human in a virtual world at all? Does the shape/look of the avatar shape the experience in the virtual world? A project like Azdel Slade's brave and compelling project "Becoming Dragon," (http://secondloop.wordpress.com/) which explored how SL could be part of the preparation for transsexual surgery by using the metaphoric transformations of a virtual world as ways of understanding and extending transgendered experience, and indeed, there is a vibrant transgendered community in Second Life.

Figure 8: Self-Design of the Avatar -- L1 evolves over time

(counter-clockwise from right).

Self-design extends beyond the avatar to being able to shape the environment, for those residents who buy land and participate in the virtual world in that way, too. Then the land, the structures they choose to put on it, also become part of what shapes their subjectivity, giving them a "home" in a world based on the metaphors of space and place. I joke that I love being able to rearrange furniture in the virtual world without anyone else's help, but the ability to customize and design one's environment without constraint is part of the appeal of the virtual world. I'll return to this aspect of virtual subjectivity under the heading of Virtual Topophilia.

VIRTUAL SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS

Nothing makes a virtual space feel more "real" than when someone else is in it with you. William Gibson imagined cyberspace as a "consensual hallucination" in his novel Neuromancer in 1984 –and we create our senses of self in a virtual world through our interactions with each other. Virtual identity is created and maintained within a social framework—inworld, people validate each other's existence and help make online identities and virtual lives more "real." There is also the element of cultural norms, aesthetics, practices, behaviors, manners, language—all the things of a culture—that contribute to virtual subjectivity. Subcultures and groups, whether informal groups of friends or organized social networking groups, can be very important in shaping an avatar's appearance, behavior, language, expectations, and other aspects of virtual subjectivity. Subjectivity is really intersubjectivity, and there is a whole new social construction of virtual reality, a plethora of them, in fact.

Figure 9: "We create our senses of self in a virtual world through our interactions with each other. It is social, and cultural, but it is done through computer-mediated communication." (E-mail sent to the data stream by L1 in V-TV, an installation in Second Life by Misprint Thursday.)

However, the ways in which people make, maintain, and experience those relationships is crucial, however, because it is through computer-mediated communication. Computer mediated communication (CMC) researcher Joseph B. Walther describes a kind of text chat that is "hyperpersonal" and allows for selective self-presentation in a way that face to face communication does not. Although Walther is not specifically discussing SL communication, his research is highly applicable to how we form and maintain social relationships in a virtual world. Computer-mediated communication like the text-based instant messaging and local chat which is still the prevalent mode of communication in Second Life despite the availability of voice, has several factors which foster a more idealized self-presentation than face to face communication. In his essay, "Selective self-presentation in computer-mediated communication: Hyperpersonal dimensions of technology, language, and cognition," Walther describes four ways people use CMC to manage impressions and enhance their message:

- it is editable,

- it is possible to spend more time on a typed communication than on an utterance of speech, even in a concurrent text chat

- it is removed from non-verbal cues that might undercut the language that is chosen, and

- it allows for a reallocation of resources from the kinds of decodings that come into play in face to face communication8

There is a feedback loop involved as well, because the two people involved in the conversation who are shaping their online or inworld friendship with CMC are both creating a persona in SL through the self-design of an avatar, and each is decoding the text messages, shaped through the affordances of CMC, in a low-cue environment, so that they are interpreting the already carefully crafted self-presentation how they want to see it. This is a powerful filter, or magnifying process.

The hyperpersonal communication feedback loop also plays into the element of control that is a strong factor in the appeal of virtual worlds—this connects with virtual agency, below. Although almost everything can be shaped and customized infinitely in SL, that does not include the other people, but sometimes I think that the mode of communication, and the polite discourse that has evolved culturally in that virtual world, leads people to hear only what they want to hear, until there is enough dissonance that their illusion is finally broken, and there can be a shock when one realizes the gap between points of view, most caused by misunderstandings. Inworld social relationships can veer into what people term "drama" at these moments of conflict, of incompatible expectations and perceptions. One kind of conflict I have experienced is about availability and access in the virtual world. I am often online but working within SL capturing video or working on virtual art installations, and have had two people who are in SL for purely social reasons remove me from their friends' lists angrily because I did not have time to talk with them as I approached a deadline, even though I explained what I was doing. (When I wrote that last sentence, I started to write "even though they knew what I was doing," but when I think about it, I don't know what they knew, just what I think they knew, so mired am I in my own virtual point of view; this is analogous to the actual world of course, but exacerbated by computer mediated communication, and one could also say that I did not have enough shared virtual world view with the people who defriended me in this example anyway.) 9

Nevertheless, friendships evolve and genuine understanding and knowledge of another can develop, either within the virtual world exclusively or by moving between SL forms of communication and extra-world media like email (pseudonymous and actual world addresses), instant messaging, video chat, telephone, and in person meetings. Whether actual names and locations are revealed or not, people mix the actual and the virtual in their friendships, trading details from their lives, with reality as the currency used to build trust. This progression is not radically different from getting to know someone in face-to-face situations, when often you don't know their names, or full names, or where they live, or what they do. 10

Another factor in virtual social relationships is being able to choose the level of what Pathfinder Linden (Jon Lester) calls "emotional bandwidth," the amount of emotional information that different kinds of communication, like instant messaging, text chat inworld between avatars who are in the same virtual space, emails, voice chat, video chat, or face to face interaction. In person, face-to-face communication has the widest pipeline, to use Pathfinder's metaphor, and asynchronous text has the smallest. Some people are very skilled at squeezing a lot of information and inflection through the smaller pipeline; like poets or minimalist artists, they prefer the lower bandwidth medium for aesthetic or other reasons. Text chat has a lower, or smaller, pipeline and although the typing can become tedious, it is an easier form of communication in many ways. In my personal experiences on sabbatical in SL, I found many talented and engaging writers with whom to interact in text conversation, and although I do use voice sometimes, it still seems like the natural form of communication in that virtual world. If I know about who the avatar is in the actual world, I "toggle" between the two images and identities, often so quickly that they fuse; I made a video about this phenomenon which is published on PBS Frontline's Digital Nation website: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/digitalnation/participate/?p=492 .

Figure 10: Maya Paris and L1 peer at

their actual selves.

(Photo

lightbox by Maya Paris.)

Therefore, although the ways in which virtual social relationships take on a specific manifestation in the virtual world, it is only when we say "I" to another, and are acknowledged, whether in text or voice, by them, and acknowledge them, in the synchronous interactions that transcend space and time zone differences, that virtual subjectivity takes shape.

VIRTUAL TOPOPHILIA

Topophilia is the love of the environment, and in a virtual world, one's perception, values, attitudes, and experiences of space and place (to borrow terminology from anthropologist Yi-Fu Tuan) are a large part of how a person constructs their subjectivity. It is true that everyone has to be someplace, but the choice of where that is in a virtual world is almost limitless, and someone could build a space to their specifications if something did not already exist. Almost any kind of landscape is available in Second Life: beach, urban, space, pastoral, forest, deserts, mountains, underwater. Tuan argues that "When space becomes thoroughly familiar to us, it has become place" (Space and Place, 73). People develop strong relationships to specific places, despite the ephemeral nature of the virtual world, and express dismay when places disappear, as they often do, because owners have decided not to keep them, for whatever reason. Having experiences and memories in virtual places strengthens the sense of self in the virtual world.11

More than just a dream or a daydream, being in a virtual world as an avatar means interacting with a graphical representation of space; it means redefining spatial experience. In a virtual world like Second Life, without haptic input, it is the imagination, the development of identification with the avatar and a mind-body connection that makes physical experiences seem "real." The experience of telepresence, of not just viewing through the spectatorial perspective of a kino-eye (virtual or cinematic), but experiencing through it so much so that the location of the actual body is no longer the only input of experience, means overcoming distance and redefining what it means to be.

In a virtual world, there is a wide range of interaction with place, varying from the mastery of the self-design of the environment discussed above to the sudden lack of control that can happen over the avatar's body and environment. New media theorist and pracitioner Ellen Strain distinguishes between "representational realism" and "experiential realism" with sight as the primary sensory input with the former and multisensory input for the latter; although the visual is clearly the primary field of data in a virtual world, it is not the only one, and depending on how one experiences the social, physical, auditory, and mobile aspects of the virtual world, the other kinds of input could become just as important. In an unfamiliar space, or in a space with a lot of lag, it can be difficult to move, to control one's avatar. If the visuals are slow to "rezz," to resolve on the screen, then one's experience is of being unable to see who or what is around, unable to know where to go or how to move effectively. As people "explore" new sims and builds either through searching, looking in other avatars' profile picks, by joining groups that send out notices about interesting places, reading blogs, trading landmarks with friends, or wandering/flying around as virtual flaneurs/flaneuses, not quite the data cowboys imagined by William Gibson (and held up by Manovich as the database flaneurs of the future), but engaged in journeying and making narratives of their virtual experiences through their uses of the virtual kino-eye. Perhaps as they go into unfamiliar virtual terrain, they may even take what we could term a kind of "tourist gaze," which Strain defines as "characterized by the constant push and pull of distanced immersion, by the desire to be fully immersed in an environment yet literally or figuratively distanced from the scene in order to occupy a comfortable viewing position" (27). It is interesting to consider the possibilities of familiar and unfamiliar, home and abroad, in a virtual world.

For now, the mobile avatar and even more mobile kinetic kino-eye through which a person experiences virtual space and place is physically housed in an immobile body, in front of a computer and screen, but that is fast changing, as more applications are available on mobile devices, and as more kinds of haptic input devices develop.12 Moreover, some studies show a positive correlation between avatar activity and increased fitness activity, or people's ability to master a physical task in the actual world after experiencing it or simulating it in a virtual context.13

As a final note on how the experience of virtual space and place shapes virtual subjectivity, Tuan comments that "Distance is distance from self" (47), but in a virtual world, notions of distance—and self—are less well defined. If visual point of view is no longer tied to the body's eyes, but liberated in the kinetic virtual kino-eye, and if the avatar body can teleport from point to point in an instant, distance from self can be erased in a blink, or a click. And if the self is both sitting at the computer—or moving around and logged in on a mobile device, using various kinds of input that might be more physical than a mouse—and kinetic in the virtual world, interacting with people virtually from around the world, what is distance?

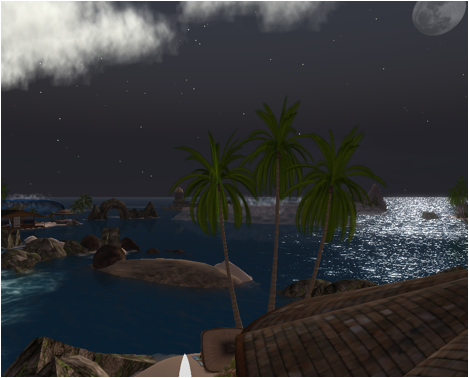

Figure 11: A moonlit night at the Monkey Cove sims in Second Life.

VIRTUAL AGENCY

Agency is the capacity to act in the world, to effect it. Participants have a high degree of agency in SL; artists and builders are particularly interested in Second Life over other virtual worlds because all the content is created by the residents, and they can build things with the inworld tools as well as use software outside of SL and upload textures, sculpted prim maps, sounds, and animations. Creative people who are not interested in building or making art per se can still self-design their avatars and environments, buying the creations of others, enacting a postmodern bricolage of identity making that can change as much and often as they want to. People can participate in groups that are organized around just about any activity or interest imaginable, and if a group did not exist, a person could start one. Whether one thinks of it as creativity, design, consumption, or participation, the specific platform of Second life affords people a high degree of control over their environment and activities.

Depending on what activities participants are engaged in, they are going to have very different first-person experiences of what it means to be an "I." If a person comes into Second Life and spends most of their time in role play games, then SL will feel like a MMPORPG (massively multiplayer online role playing game). If they go into SL to "perform" live music by streaming themselves playing music while their avatar does animations in venues while other avatars listen and dance (and possibly tip inworld, buy CDs online, or go to performances in the actual world), then SL will be a virtual venue, with its own technical, economic, and artistic benefits and challenges, with a very different experience from someone whose avatar surfs, whether as part of one of the competitive surfing groups, or just for fun at one of the gorgeous SL beaches. Some people are in SL for social reasons, others for professional ones. People come in for one reason, and find others, as they learn new skills and can participate in the virtual world in ways they didn't expect, and there are various issues around the increasing use of SL for professional reasons, including conflict around pseudonymity, the use of alternative accounts, and the possibility of dress codes for avatars (http://www.thestandard.com/news/2009/10/09/gartner-rise-virtual-worlds-will-lead-dress-codes-avatars). The ability to create content in the specific platform and interface of Second Life is what draws so many artists to that virtual world and not others.

What it means to say "I" in the virtual world, how closely related the avatar self is to the actual self, is connected to what the person is doing there in the virtual world. For me as a teacher and an artist, I want my avatar L1Aura Loire to be similar to me, both in appearance and in persona. For others, the appeal of the virtual world is the difference between the virtual self and the actual self. There is no unified Second Life experience, not only because of the individualized nature of virtual subjectivity, with each person choosing his or her own virtual point of view and expressing themselves through the choices of self-design, but also because there is no central experience other than navigating the virtual space with an avatar, and using some form of communication with others (or choosing not to).

Virtual art is a particularly interesting aspect of Second Life, in part because it often self-consciously and self-reflexively comments on the experience of being in the virtual world. There are as many different kinds of virtual art as there are kinds of actual world art, ranging from uploaded 2D images "hung" on gallery walls (which I think of more as virtual exhibition than virtual art), to immersive and interactive installations that use the some or all of the full array of SL: sound, avatar animations and movement, the SL physics engine, video, particles, scripted objects, as well as textures, sculpted prims, and other objects. My own virtual art installations tend to explore ideas that I am also thinking about in my research, and I am trying to experiment with new forms for doing that at the same time that I create pieces that immerse the avatar within an interactive environment, playing with a paradox of closeness and distance, of aura and simulation. (See the machinima "The Future of Virtual Subjectivity at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tPfwQGQHkMo and inworld at http://slurl.com/secondlife/Fiteiro%20Cultural/103/55/21 .)

There is also a virtual art scene, with many groups, large and small, devoted to making, sharing, and celebrating the astonishing creativity and talent of SL residents. There are opening parties for individual and group shows with dancing to live music streamed inworld, sneak previews for groups, prizes, exclusive group shows, practitioners of similar kinds of art gravitating towards each other and developing theories and methods, galleries, collaborations, patronage, and other aspects of the actual world art worlds.

Among the many art collectives and groups, one project in particular caught my attention, in equal parts for its good art, experimentation, democratic impulse, mixture of theory and practice, and not least because of its ludic spirit. Brooklyn Is Watching (http://brooklyniswatching.com), and in SL at http://slurl.com/secondlife/Push/72/45/22 has a sim (land in SL) where people can build art installations and others can critique it, in podcasts that are posted on the web and in itunes, and in blog postings. It is a democratic project, in that anyone can build there, and encourages conversation about virtual art. There is also a 52-inch screen in an art gallery in Brooklyn, NY, Jack the Pelican Presents "http://www.jackthepelicanpresents.com/") that has an avatar, Monet Destiny, logged into SL on the BIW sim. This project fosters virtual agency in providing a space for artists to build, a place for people to build communicate across the actual/virtual boundary, and a bridge to real world critique. As a mixed reality project, it makes the screen that shows SL in Jack the Pelican Presents into a 2-way window, into a portal, that prefigures a future in which we will move between virtual and actual realities, heightening our agency in each, as technology develops that facilitates mixed reality, or augmented reality in art, commerce, education, and other arenas. It creates community, both in the virtual and actual worlds, and the events around the Year One celebration in summer 2009, including a panel discussion that I was on in the gallery, as well as many events inworld, brought people together and called our attention to the variety and kinds of virtual art being made. BIW is in transition, after the focus on the Best of Year One Festival over the summer and recent moves from a corporate sim to the Kansas University Art Department's sim, and then to a sim generously provided by Soup and Lovers Lane Studios (see: http://soup-spoon.blogspot.com/). I hope that the artists whose work has exemplified the best and most innovative art in SL will continue to plop their pieces down next to each other, where we can see and talk about them.

Figure 12: Brooklyn is Watching

CONCLUSION

I also have a glimpse of a kind of virtual subjectivity that I would associate with the trickster—shapeshifter, crosser of boundaries, culture hero or heroine who embodies and enacts central cultural conflicts—a virtual subjectivity that would reveal all of the virtual world as installation space and oneself as a performance artist within it, calling our attention to the boundaries between the physical and virtual worlds by finding new ways of crossing them, looping between them, shifting the borders, again and again. This is a ludic subjectivity, constructed through the virtual kino-eye, engaged in the serious play of remaking the potential in all possible realities, and I would like to end this piece with my machinima "The Falling Woman Story," which explores that perspective. Falling in Second Life, perceived either from a first-person perspective or from afar with the kino-eye, is one of the fascinations for me in the virtual world. I have my avatar fall from great heights often. At first, it made me queasy--the whole fear of falling thing made manifest. But soon I understood that L1 couldn't get hurt, and I started to like it. I fall whenever I can. I like the way the dresses move on the descent. I like the feeling of letting go. I like the animation that plays when she gets up and dusts herself off afterwards. No harm done. If the future brings augmented reality, or mixed reality, in which we "toggle" or combine the actual and the virtual, whether imaginatively or through haptics, a ludic subjectivity that embraces falling, that finds fun in our fear of falling, that constructs the experience of the betwixt and between of falling through the virtual kino-eye, will further our explorations in this new frontier. (See Machinima: Falling Woman Story.)

About the Author

Lori Landay, Associate Professor of Cultural Studies at Berklee College of Music, is an interdisciplinary scholar and new media artist exploring the making of visual meaning in twentieth- and twenty first-century American culture. She is the author of Madcaps, Screwballs, and Con Women: The Female Trickster in American Culture, articles on virtual worlds, digital narrative, silent film, I Love Lucy, and other topics, and the forthcoming book, I Love Lucy. Her creative work includes machinima, virtual art installations, creative documentary, digital video, web design, and music video. She is also Aura Loire in the virtual world Second Life.

Bibliography

Battaglia, D., ed. (1995). Rhetorics of Self-Making. University of California Press.

Blakeslee, S. (2006). "Cells That Read Minds." The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-03-23, from http://www.nytimes.com/2006/01/10/science/10mirr.html

Boellstorff, T. (2008). Coming of Age in Second Life: An Anthropologist Explores the Virtually Human. Princeton University Press.

Casetti, Francesco. Inside the Gaze: The Fiction Film and Its Spectator. Bloomington, IN: Indiana UP, 1998.

Cooper, S. (2002). Technoculture and Critical Theory: In the Service of the Machine? Routledge.

Curtis , A. "THE CLAUSTRUM: Sequestration of Cyberspace." (2007). Psychoanalytic Review, 94(1), 99-139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/prev.2007.94.1.99

Friedberg, Anne. Window Shopping: Cinema and the Postmodern. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Grau, Oliver. Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003.

Griffiths, Alison. Shivers Down Your Spine: Cinema, Museums, & the Immersive View. New York: Columbia UP, 2008.

Jones, Robert. "Machinimateur Wanted: The Professionalization of Machinima." Mediascape Spring 2008 http://www.tft.ucla.edu/mediascape/Spring08_MachinimateurWanted.html

Landay, L. (2008). "Having But Not Holding: Consumerism & Commodification in Second Life." Journal of Virtual Worlds Research, 1(2). Retrieved 2009-03-23, from https://journals.tdl.org/jvwr/article/view/355/265

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2001.

Mansfield, Nick. Subjectivity: Theories of the Self from Freud to Haraway. New York: New York University Press, 2000.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: Harper Perennial, 1994.

Ortner, S. (2005). "Subjectivity and Cultural Critique." Anthropological Theory Vol 5(1): 31–52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1463499605050867

Steinberg, M. (2004). Listening to Reason: Culture, Subjectivity, and Nineteenth-century Music, Princeton University Press.

Tuan, Yi-Fu. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1977.

___. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values. New York: Columbia University Press, 1974.

Vertov, D. (1985). Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov. University of California Press.

Walther, J. B. (1996). Computer-mediated communication: Impersonal, interpersonal, and hyperpersonal interaction. Communication Research, 23(1):3-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/009365096023001001

Walther, J. B., & Bunz, U. (2005). The rules of virtual groups: Trust, liking, and performance in computer-mediated communication. Journal of Communication, 55, 828-846. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2005.tb03025.x

Links

The Falling Woman Story by L1Aura Loire http://blip.tv/file/1838833

Brooklyn Is Watching blog: http://brooklyniswatching.com/

Professor Loire's Second Life http://ll2ndlife.blogspot.com/

An Emergent Second Life, Video. [28 min] Paper Tiger TV. Co- Producer and Director, Bianca Ahmadi; Associate Producer, Juan Rubio; Editor, Juan David Gonzalez; Content Director, Jason Pine. http://papertigertv.blogspot.com/2008_12_01_archive.html

Not Possible in Real Life Blog http://npirl.blogspot.com/

SLURLs (Second Life urls)

If you are logged into Second Life, and open these in a web browser, you can teleport to these locations inworld

Brooklyn Is Watching (art sim) http://slurl.com/secondlife/Push/72/45/22

Greenies big kitchen sim (a good place to start) http://slurl.com/secondlife/Greenies%20Home%20Rezzable/145/16/22

The Odd Ball (virtual world immersive rave dance party experience, defies description—Sundays 11 am PDT and Mondays 7 pm PDT) http://slurl.com/secondlife/Research%20Center/123/120/652

Chakryn Forest—look for the sculpture the Grand Odalisque http://slurl.com/secondlife/Chakryn/128/128/2

1920s Berlin http://slurl.com/secondlife/Imagine%20Peace%20Tower/128/128/2

DBD Designs, Garden shop and garden sim http://slurl.com/secondlife/Destiny%20Blue/128/128/2

PiRats Art Network http://slurl.com/secondlife/PiRats%20Art%20Network/129/127/29

Artropolis http://slurl.com/secondlife/Drymonia/178/51/252

Virtual Harlem http://slurl.com/secondlife/Virtual%20Harlem%202/30/38/2

DynaFleur http://slurl.com/secondlife/Caledon%20Kintyre/129/129/22

Flashman's Club http://slurl.com/secondlife/Olberlos/57/220/600

SL Globe Theater http://slurl.com/secondlife/sLiterary/23/13/23

Yoko Ono's Imagine Peace Tower http://slurl.com/secondlife/Imagine%20Peace%20Tower/128/128/2

Smithsonian Latino Museum http://slurl.com/secondlife/Imagine%20Peace%20Tower/128/128/2

Immersiva, art by Bryn Oh, http://slurl.com/secondlife/Immersiva/58/98/24

Museum of Robots http://slurl.com/secondlife/Imagine%20Peace%20Tower/128/128/2

Bedrock, home of the Flintstones http://slurl.com/secondlife/Drymonia/178/51/252

Caerleon Art Collective http://slurl.com/secondlife/Caerleon%20Art%20Collective2/128/128/2

Chris Marker Museum http://slurl.com/secondlife/Ouvroir/186/66/40

Tokyo Peninsula http://slurl.com/secondlife/TokyoPeninsula/2/2/2

Fiteiro Cultural, L1's installation, "The Future of Virtual Subjectivity," http://slurl.com/secondlife/Fiteiro%20Cultural/103/55/21

Good inworld orientation to Second Life: Caledon Oxbridge (Victorian Steampunk theme) http://slurl.com/secondlife/Caledon%20Oxbridge/89/195/27

Art Museum at NMC Campus West http://slurl.com/secondlife/NMC%20Campus%20West/219/132/24

StormEye Immersive Virtual Art Installation using video, sound, and dynamic sculpture http://slurl.com/secondlife/Ars%20Simulacra/156/37/26

Also: use the search button on the bottom center of the SL viewer window to find places.

Examples of Machinima

Machinima Artist Guild 2009 Award by Chantal Harvey http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=REdVUAnqhwk

First place in Drama category: My Friends Are Robots by ColeMarie Soleil

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8h0sOIREUEo

First place in Fun Category: All the Little Fishies by Toxic Menges http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=72C5IdTw4B0

First place Art Award: Prometheus by Vive Voom http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v_eVpfSEw94

See also: Mamachinima International Festival: http://mmif.org/

World of Warcraft machinima: Divided Soul by Martin Falch http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Gcs2u9SHmQ

* * * * *

The research for this Working Theory piece was supported by a Newbury Comics Faculty Fellowship at Berklee College of Music for the project "Virtual Worlds," part of Lori Landay's 2008-09 sabbatical project.

Consider a virtual guest lecture/tour of Second Life by L1Aura Loire for your media studies or other class. Contact llanday@berklee.edu for details.

EndNotes

1 Vertov, D. "The Council of Three" reprinted in Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov, Ed. Annette Michelson, trans. Kevin O'Brien. University of California Press, 1985, pp. 17-18.

2 See http://www.machinima.com/ for video made in a range of game and 3-d environments. For a blog on machinima, see also the website for the book Machinima for Dummies http://www.machinimafordummies.com/ ).

3 Bell, M. (2008). Toward a Definition of "Virtual Worlds". Journal of Virtual Worlds Research, 1(1). Retrieved 2009-04-12, from https://journals.tdl.org/jvwr/article/view/283/237

4 I've found lack of facial expressions to be the most difficult hurdle in making a screwball comedy that takes place within the world of Second Life. On the one hand, in my homage to Bringing Up Baby, I'm free to use an animated pink leopard avatar as a character, but the human characters are much more limited than live actors. In most of my machinima, I played all the characters myself, but for this one, I worked with other people, and that made the process both more interesting and more complicated. See the trailer here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yb8hlpxVejE

5 I often use the SpaceNavigator by 3Dconnexion instead of the mouse as a kind of joystick controller, which can give a steadicam kind of floatiness to a shot.

6 A good place to find out about mirror neurons is the PBS Nova site http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/sciencenow/3204/01.html

7 An Emergent Second Life, Video. [28 min] Paper Tiger TV. Co- Producer and Director, Bianca Ahmadi; Associate Producer, Juan Rubio; Editor, Juan David Gonzalez; Content Director, Jason Pine. http://papertigertv.blogspot.com/2008_12_01_archive.html

8 Walther, J. B. (2006). Selective self-presentation in computer-mediated communication: Hyperpersonal dimensions of technology, language, and cognition. Computers in Human Behavior 23 (2007), 2538-2557.

9 The interface of Second Life has many tools that mediate social interactions. The friends' list is a whole new social tool, with varying meanings around what friendship means in social media, the protocols of offering or refusing friendship, what it means to "see" that someone is online, what expectations and responsibilities that involves—whether it is like sitting on the front stoop or front porch, or it is like having a phone with voicemail). Although a person cannot control other people in a virtual world, they can "defriend" someone, or "hide" so an individual can't see that they are online. A person can even be "muted" so nothing that they communicate will be received, and they would never know that they have been muted. Or a person can choose to allow a friend to see where they are inworld on the map. An interesting example of a subculture using the interface creatively are people involved in dominance and submission relationships that use a modified viewer named Restricted Life so that "masters" can limit what a "sub" can see and do, making that metaphor manifest in the virtual world. All of these tactics of access speak to the issue of control in an environment that offers so much control in terms of self-design, point of view, the environment, activities—everything, except for the other people.

10 The analogy of people whom you get to know in a specific context, like at a gym, springs to mind. In their workout gear, they are akin to an avatar, and maybe are not recognizable on the street. You might know their first names, and some things about them, and that forms the basis of your conversation. You know they will be there at the same time as you, and you might miss them or worry about them if they didn't show up for a while. Maybe you decide to get to know someone better, beyond the casual context, and learn more about that person, and the friendship extends beyond the boundaries of the gym. But if it doesn't, or if that friendship doesn't develop into a meaningful, deep interaction, or if you find you don't have anything much in common, there is nothing intrinsically wrong with the gym, or with getting to know people at a gym.

11 There is a function in the viewer for Teleport Home, and a way to set a certain place as Home, but a "resident" has to either own the land or be part of a group that allows them that permission. "Home" and certain relationships and privileges to virtual land are intertwined with paid membership, paid rental, the generosity of others, or purchased land ownership.

12 There is a lot of research on this, but as an introduction, see http://scienceblogs.com/neurophilosophy/2009/10/the_virtual_body_illusion.php?utm_source=networkbanner&utm_medium=link

13 Dean, E., Cook, S., Keating, M., & Murphy, J. (2009). Does this Avatar Make Me Look Fat? Obesity and Interviewing in Second Life. Journal of Virtual Worlds Research, 2(2). Retrieved 2009-10-07, from https://journals.tdl.org/jvwr/article/view/621/495 The related Stanford University Virtual Human Interaction Lab projects tend to focus on the relationships between inworld and actual world attitudes and social behavior; see: http://vhil.stanford.edu/pubs/. See also, "Testing virtual reality in the classroom" Monitor on Psychology Volume 40, No. 5 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-07, from http://www.apa.org/monitor/2009/05/virtual.html