Volume 1 Issue 1 (2008) DOI:10.1349/PS1.1938-6060.A.312

A (Very) Personal History of the

First Sponsored Film Series on National Television

Stanley Rubin

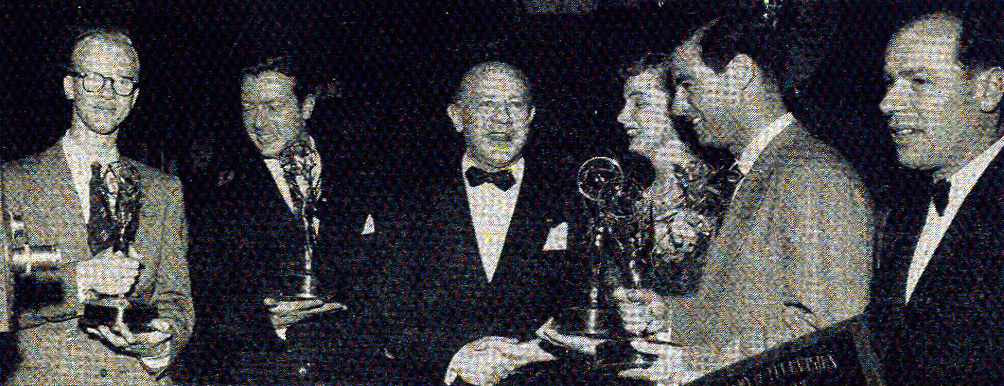

Stanley Rubin (second from the right) holds his Emmy award for "The Necklace" at the first Emmy Awards, Los Angeles 1949.

In the Spring of 1947 the option on my contract as a screenwriter at Columbia Pictures was dropped. Now I had to figure out what my next step would be if I wanted to make my living in the movie business.

What I was unaware of was that I was not alone in being dropped by a studio. This has become clear all these years later now that I'm back at UCLA for my degree, and I'm taking classes in the School of Theater, Film and Television. While I heard, at the time, of the Paramount Consent Decree, I did not realize its full significance. As the studios were forced to give up block booking and ownership of theaters "convulsions shook the town... and studios began dropping contracts with actors, writers, producers..." But all I knew then was that I was unemployed, a situation I had to correct as quickly as possible.

One thought was to come up with an original story for a feature. I had previously sold an original called "Decoy" that was being shot at the moment with a highly touted young English actress named Jean Gillie. Why not another one?

A different course of action was intriguing me, however. Television. There was a lot of talk in Hollywood about it. Nobody knew which way it would go, but it was generally agreed that once it got started it would turn out to be a voracious consumer of material. That was provocative to a young, unemployed writer. Also, the idea of getting into something on the ground floor - not just as a writer but perhaps as a producer - excited me with visions of control and ownership. I had already learned that "control" and "ownership" were two elements that writers found very difficult - no, plain impossible - to come by in feature pictures.

That decided it. The move would be to television. But what would television be looking for?

I called another writer whose option had been dropped - Lou Lantz - and explained what I was thinking of trying. He was equally intrigued, and we agreed to collaborate.

We kicked ideas around for a few days, and came to a conclusion. We would propose an anthology series - dramatizations of short stories. They would give us a virtually inexhaustible supply of material. To lure the audience back each week we would create a running character - a book shop proprietor with a great love of stories and an engaging sense of humor. In addition, his occasional narration would enable us to cover scenes it wouldn't be practical to shoot.

The two us started intensive reading sessions that led to our choice of Guy de Maupassant's "The Diamond Necklace" for our pilot dramatization. But before we could sit down and write the teleplay we had to answer the question of how long the script should run.

While the nascent TV networks were on the air a few hours each day, there were no filmed dramas to guide us. Checking series on radio was of little help. We finally decided on an interim length - a script that would be a little long for a 15-minute show, a little short if it turned out that shows would actually run 30 minutes. Either way an adjustment should not be too difficult if we were fortunate enough to make a sale.

Doing research today about what was going on at the networks some 58 years ago has revealed something ironic. The networks didn't know what length their weekly series would run. A piece in an early television magazine reports that in 1947 "a top NBC official... was assuming 20-minute segments." At the time Jerry Fairbanks Productions shot a pilot for a series titled Public Prosecutor. NBC bought it, and Fairbanks shot 26 films to fit NBC's 20-minute assumption. The series was scheduled to go on the air as the first filmed drama in September 1948. By that time, however, NBC (and two other networks) had decided on 30-minute segments! So Public Prosecutor was pulled back for additions and re-editing. The NBC vice-president who had proclaimed the 20-minute length was replaced "and another company beat Fairbanks to the punch. This newcomer to the series race was entitled 'Your Show Time'."

But let's not get ahead of the story.

Lantz and I finished our adaptation of "The Necklace" - a little long for a 15-minute series, a little short for a half-hour. The next step would normally have been an agent, but I realized we'd have more credibility if we were partnered with a going production company. That led me back to the producer who had given me my start as a screenwriter at Universal before the war. His name was Marshall Grant. He had left Universal, gathered a small staff around him, and formed his own company.

Grant was immediately intrigued with our series concept, and liked our script. He also saw television the way I saw it - a new entertainment medium with the promise of a glutton's appetite. He handed "The Necklace" to Norman Elzer, a successful businessman who had helped finance the Grant Co.

Lantz and I lucked out again. Grant and Elzer suggested that a pilot film would have a much stronger impact than just a script, and Elzer agreed to finance it in return for a partnership in the new company to be formed. Agreed! A short word with a lot of enthusiasm behind it.

So Elzer would be our money man, Lantz and I would produce it, and another member of Grant Productions, Sobey Martin, who had been a top film editor in Europe, would direct. Lou Kerner, another member of the Grant team, would help us cast the show.

It was clear to all of us that the Book Shop Man was our most important piece of casting, since he would appear in every show. I had had Barry Fitzgerald, a droll, engaging Irish character actor, in mind for the role, but he was too expensive for us. Which led to my brainstorm. Fitzgerald's younger brother, who had similar qualities, was far less known and therefore much less expensive. And that's how Arthur Shields, like brother Barry originally a member of the Abbey Players in Dublin, became our Book Shop Man.

Kerner brought in John Beal and Maria Palmer, two solid performers, to play the young couple whose lives are changed when they lose a borrowed diamond necklace, and we were basically cast.

At this point, Rudy Abel, an experienced production man, joined our team. He drew up a budget, made the rounds of studios with stage space to rent, and recommended Hal Roach. Roach was reasonable and had sets on its stages from previous productions that would work for our script, and probably be adaptable for subsequent stories - if such became the case. Abel set an inexpensive deal with Roach predicated on our committing to Roach Studios for the whole series if the pilot sold.

Our director, Sobey Martin, did a careful timing of the script and assured us that we'd wind up with enough footage and plenty of coverage for editing into a half-hour show. Our art directors, Eugene Lurie and Robert Boyle, went to work at Roach, adjusting a few standing sets to suit the needs of "The Necklace," and our cast went to Western Costume to be outfitted.

We rehearsed one day at the re-dressed sets, and then we were ready. Tomorrow would be The Big Day! We'd be shooting the way we had become used to in feature films: one camera, 35mm film, and we'd be gambling on de Maupassant's story, our teleplay, and Norman Elzer's money. As far as I can recall, the pilot shoot went a day over schedule. Our excitement over the look of the dailies calmed our nervousness over Rudy Abel's report that we would be coming in "somewhat over budget" (a harbinger of things to come).

Meanwhile there was a young agent sniffing around the Roach studio looking for something to sell to the hungry television networks. His name was Gil Ralston, and he was as ambitious and driven as we were. Within a few weeks we had a final cut, including Arthur Shields' narration, main title, credits and "canned" music. We screened "The Necklace" (by now the final title) for Ralston, and he took over from there.

Remember - this was the Spring of 1948. As I have said, the networks were hungry. So were the advertisers. And more quickly than we could ever have dreamed, Ralston was calling from New York: he had sold our series to American Tobacco for Lucky Strike cigarettes - 26 half-hours with options for succeeding years.

It's worth noting that, unlike today, the series was sold to an advertiser, and the advertiser took it to the network (NBC). As the sole sponsor, American Tobacco was in charge, and through their agency (N. W. Ayers) it was American Tobacco who dealt directly with me and my colleagues through the course of the show.

In the hope that the series would sell, we had already gone to work searching for adaptable short stories. We knew from the start that we would basically have to deal with stories in public domain because buying rights to current material would be too costly. Right after the call from Gil Ralston we did a number of things very quickly. We organized Realm Productions (R for Rubin, E for Elzer, L for Lantz, M for Martin, and inserted an A), then formed a legal partnership with Grant Productions. We also hired an attorney in Washington, D.C. who was an expert on public domain status, and made a deal for him to confirm or deny the p.d. status of each story title we submitted to him (at a fee of $25 per submission).

Our submissions cleared smoothly until one day we got a call that surprised us. To our great disappointment, the attorney told us we couldn't make Mark Twain's "Million Pound Banknote." He quickly cheered us up, however, when he went on to say we could make Samuel Clemens' "Million Pound Banknote." Only the copyright on the name Mark Twain had been renewed!

We did two more things: hired an experienced reader to expand the search for material, and spread the word around town that we were offering writers and actors a chance to break into television. That was another way of letting them know in advance that the pay would not be high.

One problem other than money was that both writers and actors were wary about dipping a toe into TV. That was probably not as much the case on the East coast, but was certainly a fact in Hollywood (and remained so for a significant number of years). Whether it was artistic snobbery or financial disdain I'm not sure, but misguided I believed it was (and I personally continued to work in both TV and films throughout my career).

At the moment, however, our main concern was finding writers we trusted to adapt the short stories we were getting cleared by our Washington attorney. Novice producers that we were, it didn't occur to us to also clear them up front with American Tobacco.

And so we hit our first conflict. Among the well-known writers whose stories we had cleared and assigned for adaptation were a few Russian greats: Tolstoy, Turgenev, Chekhov, for example. When our list of authors and stories in work finally went to American Tobacco, the roar of objection from the East didn't need a phone. No Russian writers!

I couldn't believe it. Of course I was aware of the Cold War that had erupted between us and our World War II ally - and of the formation of the House Un-American Activities Committee and the beginning of its charges of communism in Hollywood. But what did this have to do with the long-dead Russian writers we were utilizing?

I got on the phone with our sponsor's agency. I argued that our Russian writers were long-departed literary lions who had no connection with the current Soviet government. I explained that if they denied us those writers we would lose at least three scripts just completed, and one or two more in the works.

I argued... and argued... and argued... and mouthed a four-letter word when I heard the final answer. No Red Writers - exclamation point.

We took the hit and moved on. We had plenty of other elements to worry about. We were, of course, still looking for stories and writers... working on script revisions... talking to potential directors, actors and actresses.

It was now mid-summer, 1948. The series - Your Show Time - was to debut on NBC in the East in September (replacing Public Prosecutor, remember?). We wanted a lead of at least four completed shows before we went on the air. We had to start production.

Our plan was to shoot two half-hours a week. A cast reading with the director and either Lantz or me present. Minor revisions accomplished during the reading. Begin shooting after a 30-minute lunch. Finish the show lunch-time Wednesday. Right after lunch read show #2 with cast and director #2. Finish show #2 sometime on Friday. Repeat the pattern the following week while editing was under way on shows 1 and 2. Etc., etc.

According to Television International Magazine (TVI) of 1956 Your Show Time was the first production in Hollywood to go on a five-day work week. But it doesn't mention the number of Fridays when, in order to maintain our schedule of two shows a week, we had to shoot until midnight!

Earlier in this piece, I cited actors' concerns about appearing in films being made for television. But feature production continued to be cut back, and actors wanted to work, so our casting went on without too much difficulty. We settled on the same pay for every actor, Screen Actors Guild minimum of $55 a day, and to help make it palatable announced that we (the producers) were also being paid $55 a day. We didn't get "stars" but we did get competent casts, and many good players found it rewarding enough to work in more than one of our half-hours.

(In a sidelight to our casting chores there was an actress I turned down. It happened this way. I was in the editing room with Danny Cahn going over his assembly of show #3. Suddenly he brought up the name of a young actress he was dating. She was, he said, talented and beautiful but had been dropped by 20th Century-Fox, and was desperately in need of an acting job. Could I find a part for her in one of our shows? I told Danny to have her come in and read for me.

(There was a phone call, an appointment made, and the actress came in. She was truly a beautiful young lady. She briefly studied a script my secretary had ready for her, then came into my office and read with me. I thanked her and she left. Within minutes the phone rang. It was Danny wanting to know how the actress had done. I told him that though she was indeed beautiful I was not prepared to cast her in anything at this time. It was my judgment that she was still too inexperienced, and if we had difficulty with her on the set it could wreck our schedule. Danny was disappointed but accepted the decision.

Just a little over two years later I had moved on to 20th Century-Fox. I was preparing my first Cinemascope picture, and I pleaded with the studio to bring back the young actress they had dropped in '48 so I could co-star her with Robert Mitchum. The picture was River of No Return, the actress was Marilyn Monroe... and she was gracious enough never to mention my turning her down for a bit part in Your Show Time.)

But let's get back to the history of that first sponsored film series for national television.

We had shot 4 or 5 of our half-hours when we got some grim news from Rudy Abel, our production manager. Our deal with American Tobacco called for payment of $8,500 per show. Abel now had enough figures in to confirm that the shows were actually costing us over $12,000. We had to do something about the bleeding or we faced a debt of $100,000 or more by the finish of production.

We did two things simultaneously. We sent Gil Ralston back to American Tobacco to see if any renegotiation was possible - and Norman Elzer and I went to the banks to see about a loan.

Ralston was more successful than Elzer and I. American Tobacco agreed to pay $9,000 per half hour, and up the prices on the succeeding years if they picked up the options.

The banks asked what our collateral would be on the loan. Residual values, we replied.

What residual values, the banks asked. Hasn't American Tobacco bought your films?

It's more like they've leased them, we explained. They can run them on TV twice, then ownership reverts to us, and we can lease them again. That's "residual values."

But they will already have been seen,twice? Why would anyone pay to run them again, exclaimed one bank after another.

Result - no loan!

So we did what had to be done. We kept shooting and held costs down as much as possible without hurting the quality of our shows. Our writers, actors, directors, editors continued to get paid - and our debt continued to grow.

I went to bed every night assuring myself that "residual values" were for real - but when sleep came I dreamt I was drowning in a sea of red ink while the bankers sat on the shore watching and smugly shaking their heads.

In the Fall of '48 NBC opened Your Show Time on the East coast. I have not been able to track down reviews. There are, however, other signs that the series was a success. I recall being told by N. W. Ayers that we were in the Top Ten. In addition, long before they legally had to, American Tobacco offered to pick us up for a second year at $10,000 per half-hour. TVI magazine, eight years later, wrote "Not only was Your Show Time the first sponsored film series, it was the first really good film series." The article went on to say that "the shows revealed a remarkable fineness of quality considering the hectic conditions surrounding their birth."

According to a reference book of the time, NBC opened our series on the West coast January 21, 1949. TVI magazine says "series went on the air January 28, 1949 on KNBH (became KRCA in 1956)".

I cannot determine which date is correct. What I can cite with assurance is the following from Daily Variety of January 26, 1949:

"Emmy, Oscar's kid sister, made her debut at the first annual Academy of Television Arts and Sciences presentation last night... 'The Necklace' won an Emmy... as the best film made for tele. Film is one of the series titled 'Your Show Time' being produced by Grant-Realm Productions for American Tobacco."

I know the above news item is accurate. I was there (at the Hollywood Athletic Club). They called me up to the podium and handed me one of the first four Emmys awarded. I thanked everyone who had worked (or was still working) on the series, clutched the Emmy tightly, and took it home.

I don't know whether it was motivated by the award but American Tobacco once again offered to renew the series for another year at the upped price but my colleagues turned the offer down. Plainly, even my colleagues were not 100 percent certain of "residual values"! We all learned better rather soon.

After a second run by American Tobacco, all rights in the 26 films reverted to us, and we sold the package to Ziv for syndication.

Residual values no longer needed quotation marks. They were real. But because Ziv had to pay off the substantial debt we'd run up in production, they were in the driver's seat in negotiating our syndication deal - 40% for Grant-Realm, 60% for Ziv!

We're nearing the end of this tale now.

In 1975, at the request of Dr. Ruth Schwartz, I first loaned, then donated the historic series Your Show Time to the UCLA Archives of Film and Television.

As for myself, I have done a lot more television since I clutched that first Emmy, both series and TV movies. I won Emmy nominations for General Electric Theatre and Bracken's World, an Image Award for The Satchel Paige Story, and a Golden Globe for Babe, the story of Babe Didrikson Zaharias.

Year by year I have seen television shows grow more polished, reveal more intricate characters, become better written, produced and directed.

And more expensive. The difference between what we were paid by American Tobacco and what is paid for a half-hour show today is staggering. But one thing remains constant. The network involved still does not pay the full cost. If the series runs long enough, the makers and star-participants prosper - handsomely. If it flames out early, well - it's time to create the next one.

About the Author

Stanley Rubin started writing screenplays in 1940, originals and adaptations. He began producing 10 years later, both television films and feature films. He accumulated a number of awards, including the Television Academy's first Emmy in 1949 for writing and producing (in collaboration) an adaptation of Guy de Maupassant's "The Diamond Necklace". He also accumulated a wife - the lovely actress Kathleen Hughes - and collaborated with her on the production of four young Rubins, now fully grown.

Endnotes

1 Erik Barnouw, Tube of Plenty: The Evolution of American Television (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), p. 115-6. [Ed. Note: Investigated by the Justice Department for anti-trust violations, the major studios were forced to divest their theaters, were forbidden from owning any exhibition interests, and forced to adjust their booking practices.]

2 [Ed. Note: Lantz was the co-screenwriter of Crime Doctor (1943), adapted from the famous radio show, and went on to write River of No Return (1954), a feature that Stanley Rubin produced.]

3 [Ed. Note: An English translation of the Guy de Maupassant text is available online at http://www.online-literature.com/maupassant/206.]

4 Television International Magazine, 1956.

5 [Ed. Note: Jerry Fairbanks was born in San Francisco, CA, Nov. 1, 1904; was a cameraman (1924-29); formed his production company in the early 1930s; produced films for Universal pictures including a series of short color films entitled, Strange As It Seems, based on the cartoon series of the same name; moved to Paramount pictures in 1936 where he produced the Popular science series, in collaboration with Popular Science magazine, Unusual Occupations; in 1947, while at Paramount, Fairbanks worked for NBC to establish a film division which resulted in the formation of the NBC newsreel; filmed the first dramatic series for television, Public Prosecutor, the first cartoon series for television, Crusader Rabbit, and other series including "Front Page Detective," "Hollywood Theatre," This Is Your Life, The Ed Wynn Show, and The Edgar Bergen Show; starting in the 1950s, the company engaged primarily in producing films for non-theatrical use; Jerry Fairbanks' numerous contributions to the television industry include the Academy Award winning DuoPlane Process, used in the series Speaking Of Animals, the Multicam System, which allowed the filming of continuous sequences and spontaneity of live performances, and the "Zoomar Lens" which allowed a zoom from long-shots to close-ups; retired in 1983 and died in 1995. Biographical information from UCLA Special Collections Finding Aid.]

6 Television International Magazine, 1956.

7 [Ed. Note: What appears to be a final shooting script of "The Diamond Necklace" is available online at http://www.geocities.com/emruf2/yst1.html.]

8 [Ed. Note: Grant began his career as a summer stock actor, moved to the New York stage, and became a production assistant at RKO in 1936. By 1940 he was an associate producer at Universal, producing several films written or co-written by Rubin, including South to Karanga (1940), San Fransisco Docks (1940), Mr. Dynamite (1941), and Bombay Clipper (1942).]

9 [Ed. Note: Beal was an actor originally from Missouri. He first appeared on screen in 1933 and was featured in films such as The Little Minister (1934), Les Miserables (1935), Madame X (1937), and Stand By, All Networks (1942). He enlisted in the Army Air Force in 1944, and returned to act in films and television until 1993. Maria Palmer was a prize-winning actress from Vienna who performed as a child for Max Reinhardt and studied Drama and Voice at the Vienna conservatory. She appeared on Broadway in John Steinbeck's The Moon is Down (1942), and her early film credits include Mission to Moscow (1943). She appeared in several films and a great many television shows, including her own local Los Angeles show, Sincerely, Maria Palmer in the early 1960s.

10 Robert Boyle went on to work with Alfred Hitchcock on a number of his films.

11 Confirmed by Danny Cahn, a member of our editing team. Cahn went on to be come a key editor on I Love Lucy.

12 [Ed. Note: For an excellent introduction to HUAC and the communist scare in Hollywood, see Larry Ceplair and Steven Englund's The Inquisition in Hollywood (Garden City, New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1980).

13 TV Drama Series.

14 No objective tests were run on this statement; it must remain a personal opinion.