Volume 4 Issue 1 (2015) DOI:10.1349/PS1.1938-6060.A.449

Queen for a Day: Gender, Representation, and Materiality in Elizabeth II's Televised Coronation

Jennifer Clark

The televised coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953 was defined by the gender of the monarch at its center. Or, as the Chicago Tribune put it, "If a king were to be the star June 2, the glamour surely would be not so compelling."1 Prevailing narratives about the exceptional nature of a female monarch underscored the importance of the queen's femininity; this quality was primarily responsible for fostering interest in the ceremony. A young, elegant queen provided a spectacle that not only helped sustain the British monarchy in uncertain times, but also aided in the success of television and its abilities to promote itself as a technological and aesthetic wonder. With promises to effectively capture and deliver the amorphous qualities of royal glamour to its audiences, British television of the early 1950s was defined and expanded through the coronation and its queen.

It is not surprising to argue for the interconnected nature of television and the coronation, or that gender matters in this relationship. Such fundamental assertions found the investigations presented in this essay and classify them as a contribution to feminist television studies. By teasing out the implications of the value of the compelling glamour associated with Elizabeth II, Ialso consider what this decidedly visual quality produces and masks in the meeting of the coronation and television. The appeals of the keyword glamour extend beyond the simple description of Elizabeth as a fashionable, fascinating woman. Glamour emphasizes the intangible and ephemeral; it offers an alternative to embodiment and stasis. As Stephen Gundle describes it in his cultural history on the subject, by "defying the limitations of the physical body," glamour unmoors the body from a solidly material framework and offers highly visual fantasies in its stead.2

In spite of the visual qualities that seem to place it firmly and exclusively in the realm of representation, glamour is inextricably linked to material culture in two significant ways. The first, as understood through a "Marxist position," involves "material resources, labour, production, consumption and exchange."3 Glamour, per Gundle, constructs an "alluring image that is closely related to consumption."4 The enviable lifestyle associated with glamour provides incentives to replicate it via consumerist behaviors. The second way glamour relates to material culture involves the corporeal presence and exertions of the body, or what Elizabeth Grosz describes as "bodies in their concrete specificities."5 The body, in its fleshy object status, engages cultural categories of identity and value through "sexual specificity, questions about kinds of bodies, what their differences are, and what their products and consequences might be."6

The points of connection between the representational aspects of glamour and its material foundation (the body) and outcome (consumerism) are often difficult to discern, in part because of cultural investments in keeping representation and materiality separate. Capitalism's "soft power" works through glamour in its subtle evocation of desire and self-determined interests on the part of the consumer-participant.7 We engage in consumerist practices not because we are told to, but because we want to—we identify with the figure of glamour or aspire to better living. Glamour, then, does not seem to be linked to the mechanisms of capital. Similarly, the work necessary on the part of a particular body to effect glamour intrudes upon key fantasies of effortlessness. Working hard, even at being glamorous, seems incompatible with the ease of glamour. The materiality of glamour, when made obvious, disrupts glamour's central pleasures and therefore must be occluded in order for glamour to do its job.

Queen Elizabeth II's televised coronation and its aftermath demonstrate myriad concerns about the relationship between materiality and representation, particularly as they relate to gender and labor. As the coronation's archival records, representational framing, and publicity demonstrate, the activation of fantasies about amateriality reveals a host of anxieties about gender, technology, and culture. The coronation matters, in no small part, because of the production of images and the mystification of labor and embodiment involved in the meeting of a female monarch and television. The particular fantasies of disembodied, monarchal divinity; the specifically feminized allure of the queen; and the modern marvels of televisual representation and transmission of images selectively suppressed elements of materiality and supported prevailing systems of power.

In their call for scholarly understandings of visuality and materiality as co-constitutive, feminist geographers Gillian Rose and Divya P. Tolia-Kelly propose assessing the ways in which the "cultural logics of sights and things" engage one another and necessarily reside alongside each other.8 This approach, which engages both the representational (sights) and the material (things), evaluates more fully cultural practices and power relations than engagements with materiality or representation alone can do. The following critical evaluations of "'how things are made visible', 'which things are made visible' and… 'the politics of visible objects'" then become possible.9 The in/visibility of objects, bodies, labors, and sights of the televised coronation of 1953 help gauge the cultural pleasures and anxieties surrounding gender. The corresponding outcomes of the ceremonial event—in terms of images, economics, labor, and bodies—are, to again call upon Rose and Tolia-Kelly, "situated within networks, hierarchies and discourses of power" and operate in "constant dynamic process."10

The construction and effects of the monarchal image that were installed in the cultural imaginary in 1953 have since been deployed with considerable consequences. The televised coronation serves as an origin point for the ongoing effects of representing a female monarch; over time, the material effects of her image have changed considerably, yet continue to operate as a prime marker of cultural scripts about women, labor, and embodiment. To gauge the evolving legacy of the things and objects made visible in the coronation year, this essay considers the Queen's annual Christmas address, and concludes with a discussion of the 2012 Jubilee celebrations that commemorated the sixtieth year of Queen Elizabeth II's reign.

Coronation Television: Collapsing and Transforming Space

Television's place in modernizing postwar Britain was heralded through its image-based capabilities and its abilities to transcend material constraints, not through its infrastructure or its place-bound limitations. It follows, then, that television's principle value via the coronation was defined by its abilities to transport audiences through its representational reach. New York Times television critic Jack Gould praised the BBC's coronation coverage as the "first video program to be seen within the same calendar day on sets extending all the way from the fringe of the Iron Curtain in Europe to the Pacific Coast" and declared that "there could not have been a more fitting inaugural of international television."11 Anna McCarthy identifies this conceptualization of television's amateriality as a "core preoccupation with television as a form of writing across space, as remote inscription that produces—and annihilates—places: the place of the body, the place of the screen, the place of dwelling."12

The coronation helped television demonstrate its abilities to collapse geographical distances and to provide viewers with a transformative window on the world. With ABC and NBC picking up the BBC feed via the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), American audiences watched kinescope films provided by the BBC.13 American viewers encountered, in addition to the intact BBC coverage, commentary provided by the networks outside of the ceremonial footage. This commentary typically centered on the technological wonder of seeing images of the coronation on the same day as the ceremony and television's capacity to deliver elements of Britishness and translate it, when necessary, for American viewers.14 CBS commentator Walter Cronkite pointed out to audiences that the footage they were about to see was unique. They were not only watching a coronation captured for the first time on television, they were also "viewing the first films of the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth to be delivered to the continental United States."15

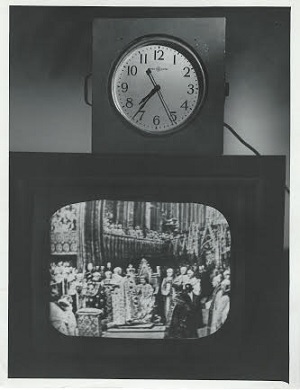

Figure 1: The expediency with which television audiences could see footage of the Coronation defined the event and evinced television's abilities to overcome the limitations of time and space.

Rather than retransmit BBC coverage via CBC, NBC and CBS aimed to transmit both the BBC's and their own footage themselves. They made plans to transport and edit this footage on specially equipped planes that would fly from London to Boston in order to be the first to televise the ceremony. After mechanical complications, NBC's plane turned back, making CBS the only network to process, edit, and transmit the BBC's and network footage successfully. Given this unique broadcast situation, CBS had a considerable investment in lauding the capabilities of television to overcome geographical distances and other material limitations. Its coverage included live reports from Boston's Logan Airfield, where its plane landed and the CBS transmission booth was located. Coverage also included CBS-produced pre- and post-ceremonial footage and commentary.

After airing the coronation ceremony filmed by BBC cameras, CBS coverage went live to the United Nations building in New York City and to the British Embassy in Washington, DC, to interview television viewers there and to watch viewers watching television.16 Correspondent Bill Wood described the embassy as a "four acre patch of British soil" set in a park comparable to Sherwood Forest that would rival the beauty of any in England. Embassy employees watching the ceremony felt that the location, with the assistance of the television's transmission of the event, was the "next best place" beyond London to experience the coronation.17 At the UN, CBS cameras established the space of the building in a low-angle shot that captured its imposing height. Correspondent Ed Morgan described the building as "a tall rectangular pile of glass and stone and steel" that would be "difficult" to "confuse" with the "mellow architecture of Westminster Abbey."18 However, given television's transportive power, the "atmosphere" of the ceremony "did invade the delegate's lounge."19

As much as New York City-UN and London-Westminster Abbey were oppositionally positioned in mood, style, and geographical place, the capacity of television to bring one to the other testified to the efficacy of television's technologies and representational powers. The transmission of the coronation transformed locations and created an "atmosphere" for viewers, who "gathered round in a sort of fireside of the world" to "watch this rather intimate familial British scene."20 Given the clearly delineated spaces of the UN and the British Embassy, this experience would be otherwise unimaginable without both the queen as maternal figure to craft a globally transportable sense of family—with she as the maternal force—and television to deliver familial scenes to populations and to record their experiences of it.

Television's formal techniques constructed the new queen as a maternal figure and her admiring subjects as appropriately loyal. Stationed along the procession route, BBC's Max Robertson reported on children lining the streets of London to greet the queen in her journey to and from the Abbey.21 Proof of this celebration was conveyed via voice-over commentary, use of close-up camera shots, and an audio track of street noise. As the queen's carriage enters the frame during the procession, voice-over commentary ceases and thereby grants her appearance solemnity and respect. With these aesthetic choices, television itself bears the signs of homage. After a cut, a closer shot features the queen and children along the parade route. The return to extradiegetic sound punctuates their enthusiastic response, with a voice-over describing "such a burst of loving cheering from these children as will now be heard in the whole of London today."22

The BBC's visual strategies underscored the new monarch's power as maternal, and thereby made it benignly persuasive. Television's capabilities to apprehend the "mother of the greatest family of nations on earth," fashioned Elizabeth's feminized, motherly influence through crowds of onlookers (particularly children) and transmitted it to audiences.23 Maternal, benevolent rule not only fit with conceptions about a female monarch, it also provided a compelling visual text that would attract viewers and would conceal the material effects of monarchal rule (for example, the maintenance of national power through economic exploitation and militaristic might) through familial representations.

Television Viewership and Consumerist Practices

The promise of seeing the new queen in her coronation moment prompted consumerist activities and economic investments in television industries. Along with the growth of BBC stations and expansion of television service, television viewing habits were energized, and the television audience grew with the prospect of seeing the queen with a media-specific immediacy and intimacy. After the announcement of the ceremony, television sets sold in Britain at a rate of a "brisk 1000 a day," with an estimated 59 percent of British adults watching the televised ceremony.24 American television networks spent an estimated $1 million apiece on the "race to air" BBC footage of the coronation, making the event a transatlantic one that reflected the networks' confidence in lucrative advertising revenues assured by audience interest in the queen.25

But it was not only the moment of coronation itself that propelled the growth of television. Elizabeth and other members of the Windsor family were constructed as television viewers more generally, with the public reassured repeatedly through journalistic accounts that the royals were early adopters and avid watchers of television. Royal relationships to television imbued television with an aura of glamour and respectability, which likely urged otherwise reluctant consumers to buy their first sets.

Royal authorization of consumerist practices had its origins in a female monarch who predated Elizabeth. During her reign, Queen Victoria (1837-1901) enacted middle classness and endorsed new ways of consuming. In doing so, she established a relationship between female royalty and idealized consumer behaviors. Margaret Homans identifies as central to the monarchy's "success" a "transformation into a popular spectacle during the 19th century; it was during that time that the association between royal spectacle and middle-class practices and values came to seem the permanent hallmark of the royal family."26 Royal associations with television of the 1950s served as a logical extension of middle-class values and commodity culture established in Britain during the Victorian era. Britishness became redefined not just through its famous "nation of shopkeepers," but through its nation of television watchers as well.

Like Victoria, Queen Elizabeth II authorized certain behaviors through domestic activities of her own and of her household. At the time of coronation, the television habits of the female royals authorized the place of television in the home and helped resolve a major public relations problem in televising the coronation: the indecency of using television cameras to capture sacred rites of the monarchy. There were claims that Elizabeth "has always been a television enthusiast," as well as reports that the ailing Dowager Queen Mother Mary (Elizabeth's grandmother) was a "television fan" and would watch the coronation ceremony via television at home.27 If, in fact, television was embraced by the Queen and her family, it could not be objectionable as a presence, by extension, either in the homes of the queen's subjects or in Westminster Abbey.

Although royal approval of television and the consumerist impulse incited by the coronation were welcomed developments for the television industry, certain female appetites incited by televising the queen exceeded the bounds of conventional gendered behaviors. Driven by their (over)identification with Elizabeth, female television viewers appeared insatiable and proved exhausting to the television industry's abilities to keep pace with their demands. According to a "network official," television programming was "loaded up with everything we [could] dig up about the Royal Family,… but the women keep writing in for more."28

The unexpected responses to the consumerist carrot dangled in front of women by coronation television bled into the private lives of women and the power they presumably sought to exert there. Concerns about the uncontrollable female viewing audience of "America's Queen-Crazy Women" led the Los Angeles Times to interview various psychologists about the issue. According to these experts, women were strongly influenced by the figure of a powerful woman. These women identified with narrative elements of a "heroine who makes them feel superior to men" and acted out resulting psychosexual drives "not to merely attract men but to rule them."29 Television provided women ample opportunities to identify with the queen and to model their behaviors accordingly. How they behaved as a result of this identification proved uncertain and revealed unintended, disruptive consequences of otherwise pro-social representations of Elizabeth.

Anxiously Watching the Queen: The Pitfalls of Televisual Capture

As a televisual subject, the queen herself was exposed to television's unpredictable and disquieting effects. Most of the time, television technology conveyed appropriately feminized and glamorous aspects of the queen and crafted images of her that could be consumed by viewers in pleasurable detail. As the Daily Mirror enthused, "Even her handbag showed on TV!"30 However, much like the unintended evocation of desires and the ceaseless consumerist appetites of the queen's female fans, television had the potential to challenge prevailing gender ideologies about the female monarch. Most particularly and worryingly, television—through the camera close-up and the immediacy of live transmission—threatened to reveal the queen's female embodiment and the gendered flesh of the monarch.

The uncertainty of the effects of television resulted in a proposed ban on television cameras at the coronation ceremony. Although it was ultimately lifted, this ban reflected a number of fears about the queen as a television subject and the ways that televisual capture would evince her embodiment. Justified by the scrutiny of the cameras—the very same media capability that conveyed minute details of Elizabeth's femininity and glamour for enraptured viewers—the ban underscored assumptions about Elizabeth's womanhood via her physicality and incapacity to appropriately execute the duties of her office. With a ceremony that would, according to Sir Robert Knox, secretary to the Coronation Committee, "demand all the Queen's concentration," live television meant that "she would be acutely conscious of every movement."31 With television cameras capturing every detail, the queen would know, if she "felt the need to touch her face or mop her brow," that "every tiny gesture…was being relayed everywhere."32

Shortly after the death of King George VI on February 6, 1952, the coronation planning committee instigated a ban on television cameras at the ceremony. The ban created a protracted and confusing saga about what should and should not be allowed to air on television. The official, public stance from the government and Buckingham Palace largely masked the will of Elizabeth herself in the decision-making process. Instead, various male authorities, primarily the members of the Coronation Executive Committee, were identified as key participants. Public outrage about the ban finally proved too persistent to be ignored. By October 27, 1952, it was reported that Prime Minister Winston Churchill was calling for a special cabinet session in order to lift the ban. The same day, a very few newspapers hinted that the "young Queen may have to decide herself whether to lift the ban," but also assured readers that Prince Phillip backed the move to permit television cameras inside the Abbey.33

There is a small, but telling mystery about whose desires were represented in the ban and its subsequent lifting. Decisions about the ban were attributed nearly exclusively to the coronation committee. A Washington Post article, published November 14, 1952, described the process this way: "Public protest against the decision [of the television ban] was so widespread that the joint coronation committee met to reconsider. As a result…the committee decided to recommend direct television of the most important features of the ceremony."34 The joint committee would then submit its decision to the "full coronation commission" for "final approval."35 Other coverage placed Churchill in special cabinet sessions at the center of the conversation with the Coronation Commission, with particular focus on Churchill as the prime mover in the affair, or as the one who "maps position" on the ban.36

A series of memos distributed among the palace, Churchill's office, the BBC, and the Coronation Committee reveals their plans to prevent the press from linking the queen to any decision about televising the ceremony. These various authorities carefully managed how the story of the ban was framed for the public. In a memo from the queen's press secretary, Richard Colville, circulated within the Coronation Committee, a plan was formulated in which the "aim must be to pipe down the story on the BBC end," and "that as there was not a line about [the lifting of the ban] in the morning papers, the right course was to say nothing and try to stamp the story right down to the ground for the next week or so."37

Although publicly the queen did not have a say in the matter, in reality she very likely was involved directly with policies about television cameras in Westminster Abbey. Sarah Bradford's biographical account of the queen's involvement indicates that "[i]t was the Queen herself who felt that she did not want such an intrusion…and privately she remained wary of this new medium; perhaps with memories of her father's agonized experiences."38 More conclusively, when Sir Robert Knox made a comment to the Yorkshire Post that went to print, the role of the Coronation Commission in buffering the queen from public critique about her decisions regarding a televised coronation became clear. A November 7, 1952, memo from Colville to the Commission indicates as much: "This [newspaper article] says that the decisions must go to the Queen herself; but all along we have taken the line publicly that these were not the Queen's decisions—that the whole object of the Coronation Commission was to insulate the Queen from direct responsibility and so from public criticism. Is this not right?"39 In correspondence between the palace and the commission, suppression of information about the issue becomes clear: "All the newspapers[,] except two[,] used the official communique and no more . . . In general a calm atmosphere has been established, although one or two Sunday newspapers may still prove difficult."40

It was only when the ban was lifted that Elizabeth was clearly linked to any decision-making processes. With months of pressure exerted by a viewing public eager to see televised images of the coronation for the first time, and with charges of a power-hungry ruling institution bent on keeping the "the people as far away from the throne as possible," the ban became indefensible.41 Only with news that the ban would be rescinded did newspapers clearly place agency with the queen, who "Throws Open Crowning to TV Cameras," as one headline put it.42 This laudatory action, the only one widely credited to the queen during the entire life of the television ban, saved her from negative publicity and further solidified her alliance with television and the "delighted millions of British TV fans."43 Idealized representations of Elizabeth as benevolent monarch, mother of a nation, and television enthusiast were preserved.

Once the ban was lifted, the presence of television cameras at the coronation ceremony presented new concerns. In particular, television's capacity to create an entertainment spectacle proved problematic. The exact nature of the formal elements of the broadcast were carefully considered and strictly limited, lest television cameras violate the sacred elements of the ceremony. Churchill, who by then was figured as the patriarchal protector of the sanctity of the ceremony, was prevailed upon to intervene. He issued a statement on October 10, 1952, in which he declared that there would be no close-ups, because the "coronation is not a theatrical piece."44

Such worries reflected anxieties about how the camera would present the queen to television viewers. If the center of a theatrical piece, then Elizabeth would appear more an entertainer than a ruling power. More concerning than the theatricalization of the ceremony and threats to the dignity of the monarchy, the ways that the camera would convey the queen's body proved highly distressing. The television camera's conveyance of the queen's body drew attention to the tangible presence of the flesh. This body, then, irrefutably signified the queen as woman. When figured as such, assumptions about her fortitude and stamina came into question, as evinced by assorted fears of brow-mopping and physical strain voiced by Coronation Committee members. A female monarch's body bore evidence of her inability to live up to the demands of the office.

This fallible woman's body would not only reveal her own personal weakness, it would threaten the perceived infallibility of the monarch and the might and right of the monarchical institution itself. Television cameras endangered fantasies of Elizabeth's disembodiment and her singular status. If Elizabeth's body was generally attributable to any woman, then she was subjected to similar patriarchal assumptions about women. Hers was a body, then, that was unable to be trusted and was no longer imbued with the status of exceptional monarch.

The complex and protracted discussions about television's alterations of the queen's image through her bodily presence indicate a longer-standing issue of the monarchal body: that of the "two bodies" of the king, as theorized by Ernst Kantorowicz. These two bodies, the Body natural and the Body politic, function as such: the natural body is subject to aging, defect, and illness, and is linked to the realistic experience of bodies that all humans experience; the politic body "cannot be seen or handled, consisting of Policy and Government, and constituted for the Direction of the People."45 Or, as Tracy Hargreaves understands this dynamic, "[t]he Body politic protects and upholds the institutional and constitutional actions of Monarchy over the individual frailties of the mortal incumbents of its Divine office: the concept of the Body politic offers continuity through its emphasis on seamless succession. Thus, the King is dead. Long live the King."46 Parliamentary papers describe the need to elide or compensate for the presence of the mortal monarchal body. They decree that "[o]n the death of the reigning monarch, the person entitled to succeed to the throne does so as soon as his or her predecessor dies," which stands as a "maxim of common law that the King never dies."47 This noncorporeality constitutes fundamental governance of the nation; thus, it is not surprising that material evidence of the monarch's body proves troubling at times and must be denied.

A female monarch's body has always been freighted with meanings that conflict with patriarchal notions of monarchal power and traditions of disembodied authority, but Elizabeth's body was uniquely enmeshed with television. In televising the coronation, the queen's "two bodies" were multiplied, extended, and explicitly gendered. Once introduced into television's representational framework, the materiality of the female body threatened conceptions of the second, sacred body of the monarch.

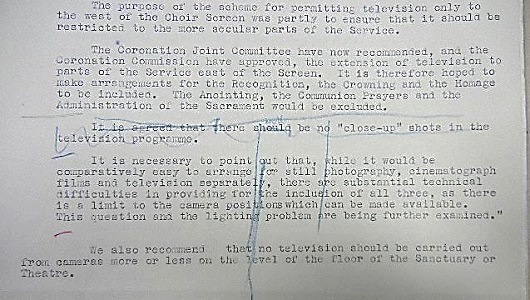

In publicized press statements, any possibility of shooting in close-up was consistently ruled out. These public pronouncements expressed the need to preserve the sacred nature of the ceremony, which made such proximity impossible. Memos that circulated between the palace and the Coronation Commission tell a different story. These documents bear witness to back-and-forth negotiations about the possibilities of using close-ups, a process that was not part of official press releases. These behind-the-scenes conversations suggest that there was not a clear rejection of the close-up, a shot that proved both dangerous and desirable. In a memo on November 13, 1952, the commission expressed its concerns that a draft press release revealed too many "technical difficulties which are still to be considered and resolved."48 The official statement should only "focus on the main announcement" about the reconsideration of the television ban.49 A second draft of a report on the use of television from the Coronation Committee bears penciled editing marks that delete the following decision: "It is agreed that there should be no 'close-up' shots in the television programme."50

Figure 2: Memos between the Palace and the Coronation Committee reveal uncertainty about how television technology will be used. (Image courtesy of The National Archives of the UK.)

Ultimately, the BBC, Buckingham Palace, and the Coronation Committee reached a compromise on the use of the close-up shot. BBC producer Peter Dimmock refrained from using "Peeping Tom" cameras, but did employ zoom lenses to capture "very special shots, like that of Prince Charles watching his mother being crowned."51 Familial moments recuperated the close-up and supplanted the problematic aspects of viewing the queen's body in such proximity. As the convoluted negotiations about the television close-up suggest, scrutiny of the queen became acceptable only in conjunction with an appropriately gendered, maternal body linked to the pathos of domesticity.

Coronation Aftermath: Women at the Center of Debates about National Television Systems

Once it aired, the coronation served as key evidence for the relative merits of American commercial and British state-sponsored television. The harmful effects of commercialism and the worst offenses of American-style television were tied to the indecorous treatment of the queen. When it broadcast the coronation, US television broke what journalistic accounts described as a "gentleman's agreement" by interrupting the broadcast with advertisements that made direct comparisons between commercial products and the queen.52 Even more egregiously, the Today Show's rebroadcast interrupted the ceremony with a comedy bit featuring the show's mascot, chimpanzee J. Fred Muggs.

Widely represented as an affront leveled at the queen personally, the problems with commercial television were articulated through gender dynamics—that of un/gentlemanly behavior and a genteel lady who was insulted by uncouth treatment. In the context of a growing possibility of sponsored television in Britain, the queen as a wronged woman became a rallying point for defense against American commercialism, its offensive nature, and its deleterious effects.

The queen was not the only victim of commercial television. The degradation of women, more generally, was used to demonstrate the ills of such a system. American television was characterized as unchivalrous at best and exploitative at worst, with hapless women at its mercy. In the BBC's charter renewal in June 1952, sponsored television became a central point of discussion, in large part because of the perceived mismanagement of US networks in their coverage of the coronation. Calling on his annual vacations to the United States, Tory MP Beverley Baxter acted the authority on the cultural distinctions between the United States and Britain. In Parliament, Baxter reported on the differences between the two countries, as evinced by their television. While conceding that he could not "entirely agree that Americans are less civilized than we are," he did propose that Americans suffered negatively from sponsored television programming. To demonstrate this, he offered an example of "the American girl," who represented "the finest of her kind in the world," yet was disgraced by commercial media's quest for profit.53 To make money, the American girl must suffer so that her imagined shortcomings would fuel consumerist responses. According to Baxter, television and radio ads claimed that she "suffers from dandruff, from body odor, from halitosis."54 He concluded, "I could go on. I do not for a moment believe it is true."55

This was not the first time that British concerns about American consumer culture had been defined by gender. From its inception, British broadcasting was defined according to gendered terms of value. In the development of radio, the BBC effectively partitioned off feminized associations with the "American popular" from "British quality." In Michele Hilmes's assessment of this practice, the BBC could identify and isolate "undisciplined, feminized 'mass' audience" that indulged "low, vulgar, sentimental, or crude tastes" and "became decisively associated with Americanness."56 Whether an unfortunate victim or a source of problems in mass culture, women figured significantly in debates about national systems of mass media. Coronation television merely extended relationships of gender, national character, and national broadcasting systems that have been part of fundamental understandings about British broadcasting since its origins.

Laboring behind the Scenes: The Material Conditions of Ceremonial Functions

Of all the women associated with the coronation, the least visible among them operated most obviously in the realm of materiality. These were the women who cleaned and organized the spaces of the ceremony and provided support for the bodily needs of the coronation participants. If the queen's labor was a source of anxiety, and if her central role in deciding television's fate at the coronation was carefully masked, then the crucial function of these women and their laboring bodies was utterly ignored. Their presence was excised from visual record, just as their labor and presence were absented from public accounts of the event. As such, their role in the coronation registers only in archival documents.

These invisible women and their work offer a record of materiality, labor, and embodiment that haunt the representational worlds of the coronation. Laboring women and the physical dimensions of their work, though a fundamental part of the ceremony, threatened to disrupt prevailing mythologies of disembodied, eternal, and sacred ceremonial events. As BBC announcer Richard Dimbleby recalled the moving mysticism of the ceremony, he felt he had been watching "something that had happened thousands of years before."57 This pleasurable illusion was shattered, however, when he spotted the litter left behind by peers. As this anecdote suggests, the material remains of the ceremonial ruptured the illusion of its purely symbolic function. Litter left behind revealed the labors and bodies involved in the maintenance of the ceremony, a fundamental and concrete reality of the day's events. As much as it was wished for, detritus and the mundane evidence of bodies and their leavings could not be excised wholly from the scene.

A bound book, Record of Procedure, Etc. compiled for and/or by the Minister of Works, logs accounts of embroiderers, secretaries, and cleaners who worked at the coronation.58 In what is simply called the "Log of Events," mundane, but vital labor is documented. Guests block passages at the Tombs and must be removed, and Mrs. Rhoda, a member of the cleaning staff, calls the main operator to report that the Annex cleaning has "been achieved."59 There are concerns of lavatory paper being removed, positive reviews of the generous supply of air freshener donated by "Messrs. Airwick," a hierarchical breakdown of lavatory attendants and their female supervisors, and a clear procedure by which the attendants could purchase their monogrammed overalls after the ceremony for £1.60 Much like the housekeeping of a private home, Westminster Abbey required the management of retiring rooms, toilets, and refreshment sites. The Record of Procedure details the labor necessitated by the coronation and plans for the sundry comforts of eating and resting, as well as minor medical treatment. Decisions were made about the types of coffee and light refreshments that were served, and which fabrics should be used to upholster various pieces of furniture in the royal family's temporary private rooms.

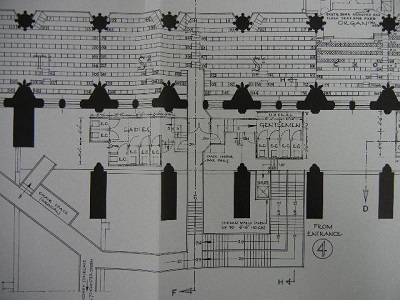

The "housekeeping" execution of the ceremony exacted effort and planning similar to that of television. Much as television networks and the BBC charted placement of cameras, microphones, and plane routes, the Ministry of Works produced detailed, bound sets of maps that plotted the locations of men and women's toilets, catering stops along the parade route, and other labor-intensive, material support that went into the day's proceedings.61 Parallel in their mapped qualities, a comparison of both sets of plans reveals how the technological marvels of television and its promises to overcome space and time were clearly imbricated with banal, material support. What makes these plans so distinctive from each other is their varying levels of public exposure and celebration. Although the positions of the television cameras in the Abbey were made widely available to the public, the plans for toilets, catering tables, cleaning, and maintenance remained unpublicized. The crucial material support of housekeeping, provided largely by female workers, operated as a crucial infrastructure for the coronation. Unlike television's much-vaunted role in the day's events, such domesticized labor and laboring female bodies remained invisible.

Figure 3: The Ministry of Work’s plans for toilets in Westminster. (Image courtesy of The National Archives of the UK.)

Coda: The Legacy of the 1953 Coronation

Why should the coronation and the conditions of its representation and materiality concern us now? In his discussion of the Technicolor film of the coronation, A Queen Is Crowned (1953), James Chapman argues that, with the ever-increasing publicity of royal scandals and a corresponding lack of reverence for the monarchy, archival moments of the coronation no longer register in public memory or in academic histories. In spite of this, I propose reconsidering not just the historical importance of visual representations of the coronation, as Chapman does, but the ongoing consequences of these representations. More than a "curio item" that only a "grannie in Bolton" could take seriously, the ceremony of 1953 and its legacy bear meaning in their contemporary effects.62

After the coronation, the queen continued to address the nation through television in selective fashion and in highly distinctive moments. Perhaps most clearly, her annual televised Christmas address carried on the pleasures of seeing the queen in a manner like no other, conveying viewer intimacy with her, and reasserting the familial and maternal terms of her rule. The first of any to be televised, the queen's Christmas address of 1957 was shot on location at the Sandringham estate. This inaugural television event reinforced the relationship between television and the queen through distinctively gendered terms.

In this address, the queen's appearance reinforced cultural scripts about television's abilities to overcome spatial divisions and to render her familiar and familial. Facing the camera and directly addressing the at-home viewer, Elizabeth assured the audience that her "own family often gather round to watch television as they are at this moment."63 Royal television viewing linked the Windsors to the British public and helped the queen envision her subjects. Just as her own family was watching her on television, the queen assured her viewers, "[T]hat is how I imagine you now."64

Simultaneity of experience, coexistence of otherwise impossible commonalities between ordinary people and royals, and maternal care and attention echo the representational and ideological management of the queen on her coronation day. Just as then, television granted audiences a visceral opportunity to understand the queen as familiar; she became just another woman who existed in a domestic idyll into which she invited viewers. At the opening of her 1957 Christmas address, Elizabeth explicitly called upon what she praised as the "more personal and direct" effects of the televisual medium. Seated at a desk, flanked by family pictures, and shot in full shot (to better capture the mise-en-scène), medium shot, and medium close-up (to better capture the intimacy of address and to capture details of the queen's visage), Elizabeth extolled the virtues of television's representational power to deliver her unto her people: "It's inevitable that I should seem a rather remote figure to many of you. A successor to the kings and queens of history. Someone whose face may be familiar in newspapers and films, but who never really touches your personal lives. But now, at least for a few minutes, I welcome you to the peace of my own home."65

Figures 4-6: Television's ceremonial moments deliver maternal and domestic spectacle, as well as intimacy with the Queen. The Christmas Broadcast, 1957 http://www.royal.gov.uk/imagesandbroadcasts/thequeenschristmasbroadcasts/

christmasbroadcasts/christmasbroadcast1957.aspx

The queen's annual televised Christmas address continued the traditions of technological and representational wonder established in the coronation moment. The address also brought with it similar anxieties about the embodiment of the female royal and television's capacity to reveal it in incorrect fashion. As much as it promised unmediated access to the queen and crafted her as both glamorous and maternal—idealized and intangible qualities of femininity—the televised Christmas address also faced the challenges of an undeniable and problematic physicality of the queen. The queen's pregnancy with Prince Edward in 1963 indisputably evinced her embodiment. As a result, the televised Christmas address was suspended for the first and only time.66

Since the initial meeting of the queen and television in 1953, the queen's presence on television continued to provide her a persuasive means by which to address the nation. But, in the intervening years, clearly much has changed in the relationship of British royalty to media outlets. With growing public knowledge of the royals' personal turmoil, as in the case of Prince Charles and Princess Diana, televised biopics began to feature "commonplace re-enactments of the private lives of the Royals within the frames of conventional romance and soap opera."67 The increased visibility of the House of Windsor, according to Giselle Bastin's timeline, had roots in A Queen Is Crowned, ramped up with the televised documentary Royal Family (1969), and reached new heights by the 1980s when "the daylight had well and truly flooded in."68 At this point, a "new era" began, "one marked by mass exposure and with increased levels of dialogic participation with the media on the part of the younger Royals."69

The very act of representing the queen has also shifted: televising the queen is no longer an intensely provocative issue, the monarchy has been reframed as a less powerful and more benevolent-seeming institution, Britain occupies increased distance from assumptions of empire, and the older and presumably desexualized body of the queen poses fewer ideological challenges. Elizabeth has become "our nation's Granny," as she is now repeatedly and fondly hailed in televised interviews with the various heirs to the throne.70 Her maternal nature more harmoniously inflects her monarchal role. As Prince William put it in his interview with Alan Titchmarsh for ITV's June 2012 documentary, Elizabeth: Queen, Wife, Mother, it is now unclear whether Elizabeth signifies as "granny" or "queen" first. But rather than assuming only that the queen is safely relegated to endearing and symbolic function, I suggest thinking that the queen and her embodiment still generates significant effects, just as her monarchal presence activates labor practices that are clearly linked to her status as a woman.

The coronation inaugurated relationships between embodiment, consumerism, and labor and the ceremonial function of a female monarch that have persisted and evolved. In the early 1950s, Queen Elizabeth II generated desires and anxieties about technological process and gendered embodiment in conjunction with the emergence of national and transnational television. In the early 2010s, the queen stimulated privatization of public works and commercialization of public interests through concerns of the nation. Her effect now, as then, is heightened particularly during ceremonial moments. As the Jubilee celebrations of June 2012 prove, the queen continues to matter, and gender continues to play a central role in the dissemination and effects of her image and presence.

The Jubilee's ceremonial, monarchal functions drew crowds, which television put on display and whose behaviors and attitudes were analyzed thoroughly. Although the Jubilee celebrations featured spectacular events, television more frequently represented the festivities through everyday, commonplace moments. Television coverage included street parties and cake baking, while television commentators, one after the other, reassured viewers that the rainy and cold June days were quite British indeed, as were the crowds' cheerful abilities to endure it. This televised content and commentary confirms Michael Billig's notion about "banal nationalism" and the ways in which national identity is built and sustained.71 Weather, for instance, defines the nation, in Billig's formulation, when the weather map is not identified as linked to a specific geographical site (for example, London) or that the weather outside is not particular weather, but rather is implied to be universal weather (for example, "the" weather). In the linguistic unit of deixis, "the" is the seemingly insignificant unit of meaning that relies on context to bear its full weight.

If, indeed, we can identify nationalism, to cite Billig, "near the surface of contemporary life," a study of visual culture and its seeming banality complements the "linguistically microscopic" approach Billig takes to analyze nationalism.72 The smallest and seemingly least consequential units of meanings—whether they are words or images—signify. And if, in linguistic terms, deixis—a "word or expression whose meaning is dependent on the context in which it is used"—relies on, yet masks or assumes the referent, then an isolated visual image, in all of its seeming insignificance, comes to mean much more.73 The single image or word can only be understood fully, then, when considered in concert with other images and broader contexts.

Corporate investments in the Jubilee depended on banal meaning making. Pret A Manger placed signage outside of its London stores requesting a seemingly simple and innocuous request, to "keep it clean for the Queen." Just as "the" of "the Queen" qualifies as deixis, the visual cues and the imperative of the sign bear significance beyond a single iteration. By linking what appears to be benign good manners—itself a systematized way of speaking to the manner of British national character—to a host of issues involved with domestic upkeep, the promise of the presence of the queen activates them all. With this prosaic request, the ceremonial events of Jubilee celebrations vitalize the corporatization of public works in Britain.

Figure 7

Pret was not alone in its investments in domestic order. Proctor & Gamble launched a campaign that chastened the public for its slovenly housekeeping on the eve of the ceremonial events of summer 2012. With a motto, "Let's Get Cleaning, The World's Coming Round," the P&G Capital Clean Up campaign enlisted the support of London mayor Boris Johnson to ask that citizens volunteer to clean up their neighborhoods. The promise of the queen's presence and a quintessentially tidy British nation, along with impending Olympic Games, created increased tourism and tourist dollars in London. In order to best capitalize on this economic uplift, citizens were compelled to participate in reordering the city according to proper British standards of tidiness. The cooperative imperative of "Let's Get Cleaning" gently goaded the British public to volunteer their labors to improve the material conditions of their neighborhoods. Civic pride and a sense of domesticated good manners disciplined populations for the sake of corporate interests. By supporting Proctor &Gamble's promotional campaign presented as a collective effort to showcase London in its best light, the willing bodies of the citizenry not only cooperated with corporate interests, they replaced government services and activated consumerist energies for the benefit of corporations.

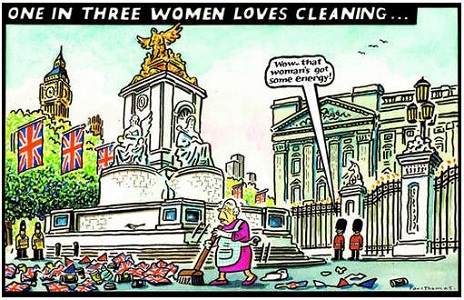

As these examples of cleaning up for "the" queen suggest, what remains of the coronation are its material traces and activation of feminized labor that were both central to and elided in public presentations of the ceremony. This legacy has important effects for the commodified, branded nation, particularly in moments when the ceremonial takes center stage. It also bears out gendered negotiations of women, labor, and pleasure in postfeminist culture. In the aftermath of the Jubilee celebrations, the Daily Express published a cartoon of the queen sweeping up the detritus of the celebrations in front of Buckingham Palace while one of her guards observes to the other, "Wow…that woman's got some energy!"74 The caption for the cartoon reads "One in Three Women Love Cleaning," a reference to a 2012 study commissioned, not coincidentally, by Zoflora disinfectant company.

Figure 8: (Image, printed in Daily Express, courtesy of Paul Thomas, paulthomascartoons.co.uk)

Widely publicized in UK newspapers, the study found that one in three women felt domestic labor to be her pleasure. In journalistic coverage, these findings were illustrated with evidence of women's labor put into the service of nation, as in the Daily Express cartoon and in the Belfast Telegraph's photograph of a female cleaning staff member wiping down the front door of 10 Downing Street.75

Such labor is reconceptualized not as material effort in service of the functioning of governance, but as self-motivated, self-empowered, voluntary, and pleasurable acts for women. Sweeping up litter becomes evidence of the female monarch's energies, just as the maintenance of the prime minister's office and residence is "woman's work," now redefined as not-work-at-all. Extending this approach to work to all British (female) subjects, keeping up one's home is a woman's true desire, because women "secretly love cleaning," as the headline accompanying the image of the 10 Downing Street cleaning woman asserts.76

Figure 9: Belfast Telegraph, June 8, 2012

Reconfiguring housekeeping as self-directed enjoyment, volunteerism, and appropriate Britishness elides the materiality of feminized labor in favor of amorphous qualities of citizenship, duty, and pleasure. Articulations of gender in the time of intensified expressions of nation craft—in a contemporary context of economic downturns, intensified economic privatization, and postfeminist culture—a troubling definition of nation. According to Melissa Aronczyk's analysis, Britain has become newly branded in powerful ways. Contemporary branding of the nation fosters not a "renewed national image, but a renewed national reality" that "redraws the boundaries of the nation as an anachronistic space for consumers and investors, while reforming its citizens as stateless, entrepreneurial, business-minded, corporate-creative workers."77 What makes the 2012 Jubilee's expressions of nationalism potentially more invasive and gender specific than the Olympics-centered GREAT Britain campaign Aronczyk speaks of is the even more mundane qualities of feminized domestic tasks. The house-proudness, the politeness, the need to "keep it clean for the Queen" involves itself in defining particularly British traits and material outcomes in ways that make them seem natural and inevitable, even as they are powerfully dependent upon the presence of a female monarch.

About the Author

Jennifer Clark is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication and Media Studies at Fordham University. She is currently working on a book about the relationship of women's liberation and television production in the 1970s. Her most recent work, on television time travel and masculinity, has been published in New Review of Film and Television Studies.

Endnotes

1 Frank Cipriani, "Coronation to Be Highlight of British Tourist Year," Chicago Daily Tribune, March 29, 1953, G1.

2 Stephen Gundle, Glamour: A History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 4. The formative relationship between glamour and "the world of representation, where playacting and fakery were commonplace," is evinced by the linkages between glamour and celebrity (whether it is Hollywood stars or politicians or stage actors) (ibid., 10). Gundle's assessment helps ground the notion of glamour in elusive, nonmaterial issues. The very mutability of glamorous personae strongly suggests that glamour is not rooted in material realities, the "real" body, or other solidly measurable "things."

3 Christopher Tilley, "Theoretical Perspectives," in Handbook of Material Culture, ed. Christopher Tilley et. al. (London: Sage, 2006), 7.

4 Ibid., 5.

5 Elizabeth Grosz, Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), vii.

6 Ibid., vii-viii.

7 Gundle, 232.

8 Gillian Rose and Divya P. Tolia-Kelly, "Visuality/Materiality: Introducing a Manifesto for Practice" in Visuality/Materiality: Images, Objects and Practices, ed. Gillian Rose and Divya P. Tolia-Kelly (Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2012), 4.

9 Ibid., 4.

10 Ibid.

11 Jack Gould, "Coronation on Video," New York Times, June 7, 1953, 9.

12 Anna McCarthy, "From Screen to Site: Television's Material Culture, and Its Place," October 98 (Fall 2001), 93. doi: 10.2307/779064

13 American, Canadian, and Commonwealth audiences watched kinescope films, while British viewers watched live transmissions.

14 Walter Cronkite, who provided voice-over commentary for CBS's footage, would educate the audience about the solemnity and significance of the event. The journey to Westminster, the "most significant ride of her life," took Elizabeth to a coronation ceremony that was "1000 years old," and where Elizabeth would be only the sixth queen crowned in this ceremony. In addition to this semi-didactic address, Cronkite also discussed British weather and the conditions under which people camped on the streets to see the procession, and contextualized the importance of the ceremony in terms of D-Day and other historical, national events.

15 The Coronation of Queen Elizabeth, CBS, June 2, 1953, produced by Don Hewitt. T81:0281, Paley Center for Media, New York. CBS stopped its own commentary after describing the upcoming ceremonial stages: the queen kissing the Bible, signing an oath, and being anointed. It was at this point that limited commentary was taken over by BBC's Richard Dimbleby.

16 US audiences saw network-specific commentary only on content shot outside of the coronation ceremony. The BBC alone was allowed cameras inside Westminster Abbey; any moving images of the coronation itself came from the BBC or were seen by audiences in the Technicolor documentary film A Queen Is Crowned. Although last to air footage of the coronation, CBS was the only network to successfully make the transatlantic flight with its footage. For further discussion of the "race to air," see Michele Hilmes, Network Nations: A Transnational History of British and American Broadcasting (New York: Routledge, 2012), 206-16.

17 The Coronation of Queen Elizabeth.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 In addition to the five television cameras inside the Abbey, the BBC also had sixteen cameras positioned along the processional route in four different locations. British audiences were able to watch this footage transmitted by five high-powered and three low-powered stations. Annual Report and Accounts of the British Broadcasting Corporation for the Year 1953-1954 (London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1956-1957), 8-9.

22 The Coronation of Queen Elizabeth.

23 Ibid.

24 "The Elizabethan Age," Time, November 3, 1952, 79.

25 Reports on the actual cost vary. A May 25, 1953, Time article places the cost at "nearly $500,000 ("Long Live the Queen!," 67.). Newsweek estimated $1 million ("Who's On First?," June 15, 1953, 92).

26 Margaret Homans, Royal Representations: Queen Victoria and British Culture, 1837-1876 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 4.

27 L. Marsland Gander, "TV and Radio Coronation Coverage," New York Times, February 22, 1953, 13. "Queen Mary to Miss Fete," New York Times, December 8, 1952, 4.

28 "Queen Mary to Miss Fete," 4.

29 John Kord Lagemann, "America's Queen-Crazy Women," Los Angeles Times, April 26, 1953, J12.

30 Daily Mirror, June 3, 1953. Cited in Asa Briggs, The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom: Volume IV: Sound and Vision (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), 428.

31 Quoted in "The Elizabethan Age," Time, November 3, 1952, 79.

32 Ibid.

33 "Royal Ruling Expected," Los Angeles Times, October 27, 1952, 5.

34 "TV Restrictions On Coronation May Be Relaxed," Washington Post, November 14, 1952, 13.

35 Ibid.

36 "Churchill Maps Position on TV Coronation Ban," Chicago Daily Tribune, October 27, 1952, C6.

37 Memo from Richard Colville to the Coronation Commission, October 31, 1952, Prem 11, Folder 33, National Archives of the UK.

38 Sarah Bradford, Queen Elizabeth II: Her Life in Our Times (New York: Penguin, 2012), 83.

39 Memo from Richard Colville to the Coronation Commission, November 7, 1952, Prem 11, Folder 33, National Archives of the UK.

40 Ibid.

41 "Churchill Maps Position," C6.

42 "Queen Throws Open Crowning to TV Cameras," Chicago Daily Tribune, December 9, 1952, B7.

43 Ibid.

44 Quoted in "Controversy over Ban on TV at Coronation Stirs Britain," Washington Post, November 10, 1952, 4.

45 Ernst Kantorowicz, The King's Two Bodies: A Study in Mediaeval Political Theology (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 7.

46 Tracy Hargreaves, "Redressing the Queen's Two Bodies in Kate Atkinson's Behind the Scenes at the Museum," Literature & History 18:2 (Autumn 2009), 38.

47 "The Coronation Oath," House of Commons Library, Standard Note: SN/PC/00435, http://www.parliament.uk/documents/commons/lib/research/briefings/snpc-00435.pdf.

48 Memo from Richard Colville to Coronation Joint Committee, November 11, 1952, Prem 11, Folder 34, National Archives of the UK.

49 Ibid.

50 Ibid.

51 Peter Black, The Biggest Aspidistra in the World, (BBC, 1972), 178. Paraphrased in Asa Briggs, The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom: Volume IV, 426.

52 "The Commercial Touch," Time, June 19, 1953, 265.

53 Quoted in "Plugs for BBC," Time, June 23, 1952, 94.

54 Ibid.

55 Ibid.

56 Michele Hilmes, "Who We Are, Who We Are Not: Battle of the Global Paradigm" in Planet TV: A Global Television Reader, ed. Lisa Parks and Shanti Kumar (New York: NYU Press, 2003), 65.

57 Jonathan Dimbleby, Richard Dimbleby (Philadelphia: Coronet, 1977), 243. Cited in Asa Briggs, The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom: Volume IV, 430.

58 The Coronation of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2nd June 1953 and Celebrations in Connection Therein: Record of Procedure, Etc. Adopted by the Ministry of Works, Work 21, Piece 302, National Archives of the UK.

59 "Log of Events," June 2, 1953, Prem 11, Folder 33, National Archives of the UK.

60 The Coronation of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2nd June 1953 and Celebrations in Connection Therein.

61 The New York Times, for instance, published diagrams of television coverage in the Abbey. Business Week published, alongside photos of the ceremony, distance and flight times for the planes carrying footage across the Atlantic. Val Adams, "The Coronation Ceremonies on TV and Radio," New York Times, May 31, 1953. "When U.S. Television Covered Coronation," Business Week, June 6, 1953.

62 James Chapman, "Cinema Monarchy, and the Making of Heritage: A Queen Is Crowned (1953)" in British Historical Cinema, ed. Claire Monk and Amy Sargeant (New York: Routledge, 2001), 82, 89.

63 "Christmas Broadcast 1957," Official Website of the British Monarchy, http://www.royal.gov.uk/imagesandbroadcasts/thequeenschristmasbroadcasts/christmasbroadcasts/christmasbroadcast1957.aspx.

64 Ibid.

65 Ibid.

66 "Christmas Broadcast 1963," Official Website of the British Monarchy, http://www.royal.gov.uk/ImagesandBroadcasts/TheQueensChristmasBroadcasts/ChristmasBroadcasts/ChristmasBroadcast1963.aspx.

67 Giselle Bastin, "Filming the Ineffable: Biopics of the British Royal Family," a/b: Auto/Biography Studies 24:1 (Summer 2009), 35. doi: 10.1353/abs.2009.0008

68 Ibid., 39.

69 Ibid., 39.

70 Joanne Goodwin, "Celebrating the Jubilee with Our Nation's Granny," Herfordshire & Wye Valley Life, May 24, 2012, [Link]. In his ITV interview, Prince William indicates that the role of the queen has shifted from his youth, when Elizabeth was "Queen first, then grandmother," whereas now she is "definitely grandmother first, then Queen second." In the various televised interviews they granted in the United States and in the UK in conjunction with the Jubilee, Prince Harry, Princess Eugenia, and Princess Beatrice consistently speak of the queen as their endearing "granny."

71 Michael Billig, Banal Nationalism (Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1995).

72 Ibid., 94.

73 Oxford Dictionary of English, 3rd ed., ed. Angus Stevenson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010) s.v. "deictic."

74 "One in Three Women Loves Cleaning," Daily Express, June 7, 2012, http://www.express.co.uk/comment/cartoon/view/2012-06-07.

75 "Third of Women Secretly Love Cleaning," Belfast Telegraph, June 8, 2012, http://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/woman/life/third-of-women-secretly-love-cleaning-28758175.html.

76 Ibid.

77 Melissa Aronczyk, "From Henry VIII to Flash Mobs: Branding Britain at London 2012," Antenna, July 17, 2012, http://blog.commarts.wisc.edu/2012/07/17/from-henry-viii-to-flash-mobs-branding-britain-at-london-2012/.