Volume 5 Issue 1 (2016) DOI:10.1349/PS1.1938-6060.A.457

Modern Art as Media Event: Early Swedish Television and the Communication of Art Appreciation, the Case of Multikonst (1967)

David Rynell Åhlén

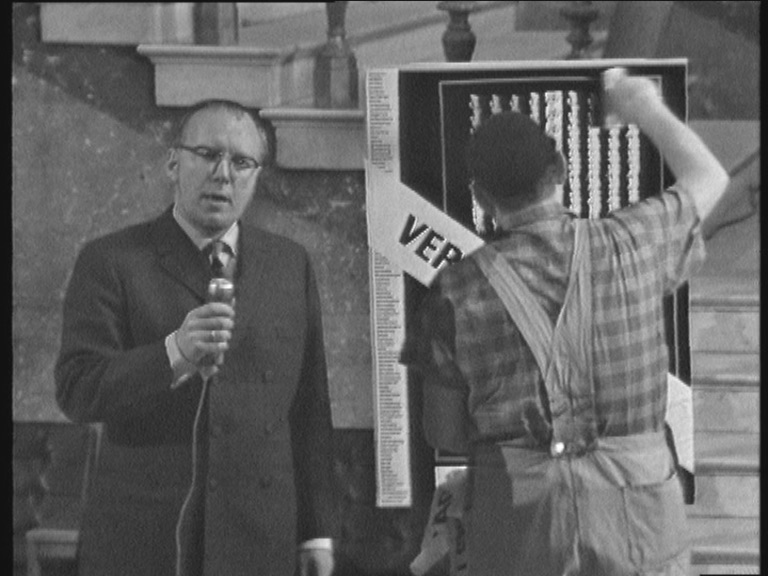

"It is a great pleasure for me to now, with the aid of television and at the same time, open 100 identical exhibitions at 100 different locations across the country."1 These words spoken by the minister of culture and education, Ragnar Edenman of the Social Democratic Party, concluded a live-to-tape address to the Swedish television audience aired around 2 p.m. on Saturday, February 11, 1967. Edenman's speech inaugurated a large-scale art exhibition project called Multikonst (Multi Art), which reached not only private living rooms across Sweden, but also a number of television sets placed in various public locations where the exhibition took place. The Multikonst project was a cooperation between Sveriges Radio (Swedish Radio Broadcasting Corporation, hereafter SR), the nongovernmental art organization Konstfrämjandet (Promoters of art), and the newly founded governmental project Statens försöksverksamhet med riksutställningar (State experimental work with nationwide exhibitions). As Edenman's words point out, Multikonst comprised a total of 100 exhibitions that were shown simultaneously all over Sweden. Aside from the ambitious scale, the organizers especially highlighted the use of broadcast television as a groundbreaking novelty of the project. In addition to broadcasting the opening address, SR produced and aired five special programs during the weeks of the exhibition.

Multikonst opening address, Swedish Radio, 1967

However, television's prominent role within the project was considered but one part of a more far-reaching "integration of media," to quote one of the organizers, and an ambition to disseminate modern art by making use of forms and strategies derived from contemporary popular media and consumer culture.2 Each of the 100 exhibitions displayed contributions from sixty-eight Swedish artists, among them modernist artists such as Siri Derkert, Sven X:et Erixson, and Lennart Rodhe, and representatives of a younger generation of 1960s artists, such as Berndt Petterson and collaborating artists Ture Sjölander and Bror Wikström. From the organizers' perspective, though, they could all be labeled modern and part of "the art of today." Modeled on the popular circulation of gramophone records and paperback books, the artists contributed works made especially for the project and for the purpose of being multiplied in large editions (hence, "multi art") and sold at the separate exhibit locations. The 100 exhibitions were identical, then, in the sense that they all displayed and made available for purchase the exact same artworks. The aim was to literally bring modern art into Swedish homes. But the distribution of modern art objects to homes all over the country was only a means to an end. The overall goal of the project was to communicate the importance and value of individual encounters with modern art. In short, it was the unique experience that was important—not the unique artwork. As Edenman also made clear in his opening address, "Our experience of art has neither to do with money, nor always with the question of whether the art work is unique or multiplied." Then he concluded, "It is such a view of art as experience, that the Swedish state wishes to support."3 How this was to be accomplished and the specific place and role of broadcast television within this enterprise are the topics of this article.

Using the Multikonst project as the empirical focal point, I will examine how broadcast television was utilized as a means of communicating the importance and meaning of modern art to the Swedish viewing public in the 1960s. The exhibition lasted for a few weeks in February and was largely considered a success by the organizers. It drew an estimated 350,000 visitors, and many of the artworks were sold. Although recognized in some historical accounts, an in-depth exploration of the issues concerning the events, their aims, execution, and repercussions still remains to be written.4 When Multikonst has been recognized in historical accounts, it has generally been in reference to a particular incident that took place during one of the programs produced and aired by SR in connection to the project, a variety show recorded at the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm in celebration of the exhibition opening. In the show, renowned actor Per Oscarsson discussed one of the artworks using what was later denounced as "foul language." The incident caused a short-lived scandal that contributed to the already widespread interest in the exhibition and, as I demonstrate in what follows, this incident can be thought of as part of the organizers' larger strategy in managing the problem of encouraging individual encounters with art at a national scale.

The case of Multikonst is here understood in light of Daniel Dayan and Elihu Katz's concept of "media event." Dayan and Katz introduced the concept of media events in the eponymous book of 1992, as a way of theorizing and investigating special kinds of broadcasted events that derive a great part of their meaning and significance from the televised mediation itself.5 As examples of media events, Dayan and Katz use royal coronations, the Olympics, and political state visits. I would like to claim that the Multikonst project also in many ways functioned as a media event. It constituted a media event in the sense that it was promoted as an interruption in everyday routine and daily television scheduling, was preplanned by a number of actors besides SR with the aim of creating a sense of national unity, and that the use of a variety of media forms was fundamental for its performance.6 The primary sources I present here include archived TV programs from the project, obtained through the Swedish Royal Library, as well as additional material such as articles from the official TV guide of the time, Röster i Radio-TV, and a book about Multikonst published by SR shortly following the event. Focusing on a selection of the project's special programming, I will consider the specific contribution of broadcast television within the exhibition project; which kinds of televisual forms, techniques, and modes of address the programs employed; how the target audience was invited to partake in it; and the value of partaking in the prescribed ways.

Mass Media and Art Education in Postwar Sweden

As evident from the opening address, the Multikonst project was chiefly guided by principles of equality. The organizers' explicit motivation was that everyone should be able to enjoy and experience art, regardless of geographical location or social and economic situation. Underlying this motivation was a concern shared by the organizing parties that Swedish citizens in general seemed uninterested in art, and particularly modern art, for it has been assumed that the audience finds modern art essentially incomprehensible. From the organizers' point of view, this had to do with the public's lack of knowledge about modern art. If they simply were to learn more and come in contact with quality artworks, the problem would solve itself. In this context, television was considered to offer a way to disseminate knowledge on art and make it more appealing, thereby creating interest in art and, it was hoped, in the long run creating a new audience for art. How might these overall aims and motivations be situated in the context of the contemporary media and cultural policy?

As in many other European countries, Swedish television was introduced as a national and noncommercial public service. With the BBC serving as a basic model for organization and program content, Swedish television was administered by Radiotjänst (from 1957 Sveriges Radio, SR) within the existing system for radio broadcasting, funded by license fees with the aim of providing culture, education, and quality entertainment to the people. Through a state agreement, SR officially started transmissions in 1956. Until the 1969 launch of a second channel, television in Sweden consisted of one channel only. SR's television monopoly lasted until the end of the 1980s, when commercial broadcasting services began.7 As Jan Olsson has noted, this path for television created a monolithic viewing environment during the early years with consequences for audience formation, modes of address, program formats, and representational matters.8 Olsson details how this particular development was not inevitable but was preceded by debates between proponents for a commercial model on the one side, and a public service model on the other. This uneasy relationship between conceptions of commercial versus quality television has continued to characterize much of the debate on television in Sweden until today.9

The development of television broadcasting, as well as the high hopes regarding its impact on art education, also tied into larger political and cultural currents. Ragnar Edenman's opening address expressly pointed out "art as experience" as a key concept of Multikonst. Earlier in the speech, he emphasized the importance of "information" in order to accomplish such an enterprise. According to this line of argument, three concepts were essential to the Multikonst project as well as for art education and state cultural policy in general: production (the creative work of artists), consumption (the audience's activities), and information. In order for consumption of artistic products to occur, according to Edenman, some kind of information was required. This emphasis on experience of the audience and on information was characteristic of changes in the cultural debate and cultural policy of the 1960s. In a famous speech in the city of Eskilstuna in 1959, Edenman had outlined the basic problem that a new cultural policy was to overcome. His point of departure was that the emerging welfare state and the overall prosperity and increased living standards of the population had failed to give rise to a corresponding increase of "the consumption of cultural goods—art, music and literature of substance and worth."10 The explicit adversary in this argument was that of commercial mass culture in the form of low-quality art, light music, and inferior movies. The right way to counter this development, according to Edenman, was "not with bans and censorship," but "with the most obvious of warfare; the offering of other options, other choices."11 Directing artists to make the art more appealing to the public was unthinkable in a modern democracy. Instead, a state cultural policy should be aimed at "breaking down the barriers between artists and the larger population, to actively work for an increased understanding of art and shape our public space in a way that stimulates interest in art and art consumption."12 Such a concept of cultural democratization and cultivation of the general public was not in any way new. Initiatives like Multikonst were only the latest in a longer historical genealogy of governmental and nongovernmental efforts to educate the public in the appreciation of arts and culture.13 However, as is evident from Edenman's speech, the 1950s and 1960s witnessed considerable changes in how such an enterprise was conceived.

Examples of what Edenman might have been referring to when speaking of "bans and censorship" can be found in the preceding decades. In the late 1930s, the State Art Council was formed with the goal of supporting Swedish artists and, while providing them with work, also providing public space for the arts. During World War II, the council issued import regulations on art in order to control the circulation of what was deemed "inferior" or "horrific" art, from the 1950s onward commonly called "hötorgskonst" (marketplace art)14. Generally, this referred to low-quality reproductions of well-known artworks or, more generally, mass-produced paintings and prints sold at cheap prices. The inferior art was considered to have a negative effect on work opportunities for Swedish artists as well as, supposedly, on public taste. These regulations were in function during the war and in a somewhat modified form until 1953.

Other strategies of counteracting the influence of inferior art were campaigns, traveling exhibitions, and lotteries. A prominent example is the exhibition God konst i hem och samlingslokaler (Good art at home and in meeting places) at Nationalmuseum in 1945. Beyond showing examples of "good art," the exhibition's pedagogics was based on showcasing examples of inferior art as comparison and a terrible warning to the audience. Most important, exemplary works of art were on sale at the exhibition, providing the audience with the opportunity to also buy and own art themselves. This exhibition marked the starting point of the activities of Konstfrämjandet, which became one of Multikonst's central organizers. Founded in 1947, the organization has since been dedicated to selling and circulating quality artworks, mainly prints by union member Swedish artists, at affordable prices. Aside from Konstfrämjandet being the initiator and one of the organizing actors of Multikonst, the 1945 exhibition was also explicitly cited as a forerunner of the project.

Before the Multikonst project, efforts at cultivating the public were based on clearly distinguishing between "good" and "bad" art.15 During the 1950s, the view of an "aesthetic fostering" of the people propagated by such efforts seems to have been increasingly difficult to uphold. Instead of inferior art being considered a problem in and of itself, it started to be treated as a consequence of the public's lack of knowledge in visual art and a general unavailability of art. A 1956 official government report on art education is a case in point with regard to this shift in emphasis.16 The report explicitly stated that instead of prohibiting certain kinds of art, efforts should be aimed at educating the public and increasing the availability of quality art. In short, the basic problem came to be identified as a problem of communication and information. This change, from strategies of prohibition and deterrence toward strategies of education and information, corresponds to broader contexts of ideas on communication.

John Durham Peters has argued that the postwar years were an important period in the history of communication, during which ideas originally developed for military purposes and telephony were given new meanings and applications.17 For example, Peters discusses information theory as a technical discourse of communication, where the transfer of electronic signals took on new significance.18 In Peters's words, this idea of communication turned relational problems "into problems of proper tuning or noise reduction."19 He also details another understanding of communication, which he terms a therapeutic discourse: "communication as cure and disease."20 Here communication is understood based on the human psyche, and an idea of the managing of communication breakdown between people also could be applicable on a global scale, a prominent example being the United Nations and especially the suborganization UNESCO. These discourses share a common denominator in the view that political and interpersonal obstacles and challenges could be solved with the use of improved technology and techniques. In the Swedish context, both these discourses seem to be in play, and the use of different media in relation to discourses on communication and information were common in several areas of culture, among them art education.21

In the early 1960s, the emphasis on audience experience in relation to art became the center of attention in cultural debates. The idea that anything can be art and the spectator's central role in the production of meaning about artworks were intensely discussed topics in what has become known as the Great Art Debate, prompted by the activities of the then recently opened Moderna Museet (Museum of Modern Art) in Stockholm, and the ideas were put forward in art critic Ulf Linde's book Spejare (1960).22 In light of this more relativistic view of art, earlier efforts at distinguishing "good" from "bad" seemed authoritarian and undemocratic.

What was television's place in all this? As Peters has noted—and as is very much applicable to the situation in Sweden—television can be seen as the centerpiece of the hopes and fears concerning communication at the time.23 In and of itself, the new medium of television could be considered part of emerging media and consumer society's threat toward arts and culture. However, as a public service institution, it was also part of the improvements of the welfare state and a potential tool for educating the public. The year of the official report quoted earlier, 1956, coincidentally also marked the official start of television transmissions in Sweden by SR. The introduction of the new medium did not go unnoticed in the report, which stated that television without doubt would revolutionize art education in the near future.24 As the research of Lynn Spigel and Katerina Loukopoulou has shown, this conception of television's potential for raising public interest in the visual arts was common among public service and commercial networks alike.25

A recurrent theme in these lines of thought was the promise of television to popularize the visual arts in the same way that radio had popularized classical music. Sweden was no exception to this international trend.26 From the point of view of SR, modern art in particular played a part in shaping future views of television. The new visual medium, it was claimed, could benefit from the ideas of modern artists. As a part of these ambitions, artists Ture Sjölander and Bror Wikström produced for SR the short experimental programs Monument and Space in the Brain that aired during the late 1960s.27 These ideas of a televisual avant-garde of sorts were admittedly not unique for the Swedish context, and as elsewhere, they were not in any way fully realized. Already by the mid-1960s, growing criticism was aimed at SR for not fulfilling its proclaimed duties toward the visual arts. Besides proposing a solution to questions of how to bring modern art to the people, the Multikonst project can in part be viewed as a response to this kind of criticism.

"A Truly Nationwide Exhibition"

In retrospect, the general idea behind Multikonst can be described as a reconceptualization of the medium of the traveling exhibition. Instrumental to this idea was the conception of television as a real-time "live" medium. Konstfrämjandet's idea was that instead of a traveling exhibition tour making 100 stops, the incorporation of broadcast television would allow for 100 exhibitions being shown simultaneously. As the organizers aptly summarized the enormous enterprise, it was "a truly nationwide exhibition."28 The concept of media events, as theorized by Dayan and Katz, provides a useful framework for thinking about the project. In line with Dayan and Katz's conception of media events as the High Holidays of mass communication, Multikonst was promoted in Sweden as an exceptional interruption in the daily routines of television scheduling and something that everyone should be a part of.29 During the weeks leading up to the exhibition opening, a variety of media was put to use advertising and promoting the project, adding to the anticipation and preparation with the public. "Multikonst" was launched as a catchphrase to create a buzz around the project and, outside of extensive coverage in the press, posters announcing the arrival of the exhibition were distributed all over the towns and localities were it was to take place.

This points to another aspect of Multikonst as a media event, namely that it was preplanned by a number of actors.30 Several organizations and institutions with their respective agendas were, as described earlier, involved in organizing the project. For Konstfrämjandet, Multikonst was thought of as a continuation of its work over the last decades and coincided with the organization's twenty-year anniversary. Riksutställningar, for its part, was set up as a practice-based division within a recently formed governmental investigation of museums and exhibition activities in Sweden, led by architect Lennart Holm. Riksutställningar had started its activities the preceding year with a touring exhibition called 100 år Nationalmusem (100 years of the National Museum of Art), showcasing masterpieces of Western art from the state museum collection.31 For Riksutställningar, then, the project carried with it the possibility not only of experimenting with new forms of exhibition concepts and design, but also of collecting data on the audience. The view underpinning the latter might be characterized with regard to the importance of information. A vital part of informing the public also meant keeping informed and gathering information on the public. This resulted in a comprehensive report based on statistical data from the project.32 Lastly, by taking part in the project, SR had the possibility of counteracting criticism of insufficient attention to the visual arts and of making audiences passive.

Multikonst was not just promoted as a novel way of disseminating and exhibiting art based on a conception of televisual logic, but also as denoting a new kind of art object. The idea of reproducing large editions of artworks and selling them at the exhibition locations was in line with the main goal of Konstfrämjandet, which, by the late 1960s, had for some time been specializing in producing large and inexpensive editions of prints by established artists. The initiative put forward in Multikonst was to expand this concept of art reproduction into the realms of all types of art, producing cheap modern artworks available for everyone. Yet, one aspect especially highlighted by the organizers was that the artworks were not to be considered reproductions. Instead, each of the artworks was to be considered an original work, although mass-produced in thousands of copies. In this sense, the multi artwork exemplifies what Noël Carroll has termed mass art, a category of art that "makes possible the simultaneous consumption of the same artwork by audiences often divided by great distance."33 Admittedly this idea was not without forerunners, which the organizers also acknowledged, mainly with reference to the contemporary works of Swiss artist Daniel Spoerri and American pop art, which in the earlier part of the 1960s had been introduced in exhibitions at the Moderna Museet. According to the organizers, however, the Multikonst initiative differed from these other instances in the sense that the project did not make use of the concept of multiplied art as an aesthetic strategy—as in the work of American pop artists and the like—but instead, it was put to use as a distributive strategy.34

The introduction of multi art as a new kind of art also entailed an explicit critique of the existing institutions and conceptions of art. This was mostly evident in statements from television producer and leading project organizer Kristian Romare, who in a very polemical fashion emphasized how art, due to a focus on exclusivity and commercial value, was becoming increasingly isolated from a majority of the public and the everyday life of the citizens.35 Romare, an art critic, was hired by SR in 1964 to be responsible for the arts programming. He presented himself as a radical and provocateur, something that did not always correspond well with SR's ideals of objectivity, appropriateness, and neutral modes of address. In connection to the Multikonst project, Romare outspokenly attacked museums, galleries, and the commercial market for art, blaming them for treating art as exclusive goods, increasingly out of touch with the times and the everyday circulation of media and consumer culture. Exactly who or what the target of this critique was remains somewhat unclear. The rhetoric functioned as a way of promoting the project as radically novel, and it echoed the official cultural policy at the time that was also manifest in Edenman's address quoted earlier, although voiced in a somewhat less polemical fashion. Romare promoted an explicitly anticommercial stance, arguing for a more democratic view of art where everyone everywhere could be able to afford and own artworks. In line with this, he characterized the project as promoting "a genuine pop art" and as a "new experiment in art propaganda and art communication" of a kind never before seen.36

How was this to be accomplished in practice? I will now move on to consider the television programs produced for the project. All in all, SR produced and broadcasted five programs in relation to the exhibition. The preparatory planning as well as the aftermath of the exhibition were covered by the evening news show Aktuellt, and the project was also covered by radio. In addition, two introductory programs were aired in the weeks leading up to the exhibition; and two days after the exhibition, a program devoted to filmed visits to the studios of some of the contributing artists was aired, a staple ingredient of arts programming at the time.37 My focus, however, is mainly on two of the special television programs: the exhibition opening variety show Multikonst—hela Sverige går på utställning and a show dedicated to audience participation that aired a week after the opening, Multikonstifikt?

Addressing the Nation

Making modern art available to all and thereby allegedly democratizing the experience of art entailed a number of notions concerning art, media, and communication. Underlying the overall aim was first of all the idea that modern art is essentially good and potentially critical. Second, the democratization of the experience of art highlights a seemingly ambivalent position toward the medium of television. This is already evident in the first programs broadcasted as part of the project, titled Bild på dig (Image of/at you) and Fri såsom bilden (Free as the image), with the joint subtitle "a talk on art," and aired in the weeks leading up to the exhibition opening.38 Poet and author Sandro Key-Åberg, by the time also an active art educator, hosted the shows and scripted them together with producer Kristian Romare. The shows were structured in the manner of a basic lecture format, with still images and short moving images illustrating the arguments. These programs can roughly be described as pedagogic introductions to the specific way of thinking about art that the exhibition promoted, as well as to the importance and value of art in modern society more generally. In line with media event attributes, the shows functioned as a way of promoting the exhibitions and contributing to anticipation and preparation on the part of the audience.

In addition, the shows also aimed at countering supposed popular (mis)conceptions of modern art. This included, for example, the more inclusive definition of the concept of art intensely debated in the 1960s, stating that everything and anything might be considered art. In this respect, the shows came into being as part of an effort to popularize the idea of art as two-way communication, acknowledging and privileging the spectator's experience and making meaning of a work of art, famously put forward by art critic Ulf Linde in the early 1960s.39 The basic message was that the apparent incomprehensibleness of modern art could be viewed as its greatest quality, the ambiguousness making possible the discovery of new ways of seeing and experiencing the world. The show illustrates this, for example, with works by Swedish-American pop artist Claes Oldenburg and his sculptures based on everyday objects such as scissors, typewriters, and light switches. But as Key-Åberg also explicitly made clear at the end of the show, in his opinion the point was not to tell the viewers what to experience when looking at art, but instead to propose how to experience art.

Outside of contributing to the creation of anticipation for the actual exhibition by suggesting a certain attitude toward art and the value of art in modern society, the shows also addressed wider issues concerning media and images in contemporary society. During the latter part of the 1960s, the writings of Marshall McLuhan had profoundly influenced Swedish art and cultural debate. His ideas on media and art were picked up by producers of SR, who took a liking to his concepts of "the medium is the message" and of television as a low-definition "cool" medium demanding a high degree of participation from the viewer. McLuhan was explicitly cited by Romare as an influence in connection to Multikonst, as is also evident in the show's overall self-reflexive design and modes of address. Already in the opening of the first program, Key-Åberg addresses the issue of mediation by describing how the television image in actuality consists of several images experienced as continuous movement. In the same vein, he goes on to use different techniques and devices to scrutinize and make visible the act of mediation and its effects on perception of art and other images. The two shows were thus popular lessons in "ways of seeing," and thereby participated in a broader international trend in arts programming that focused on visuality in relation to art and the everyday, an early example being the CBS show Revolution of the Eye premiering in 1957. This trend later famously culminated with John Berger's programs for the BBC in 1972, Ways of Seeing.40

The grand opening of the exhibition took place on the air around 2 p.m. on Saturday, February 11, with Ragnar Edenman's opening address. In time for the inauguration, each of the 100 exhibition locations had been equipped with a TV set so visitors could follow the address; this aimed at producing a sense of simultaneity and unity, creating a virtual exhibition space of national scale where every citizen from north to south was invited to take part. Later that evening, in prime time at 7:30 p.m., a variety show over forty minutes long, recorded at the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, celebrated the occasion of the opening. The nationwide address and unifying function of the show was apparent already in its title: "Multikonst—hela Sverige går på utställning" (Multi Art—the whole of Sweden goes to exhibition). In a similar fashion, the opening titles of the program showcased still-image montages of the official Multikonst poster at different locations all over the country.

Producer Kristian Romare hosted the show, interviewed guests, and provided voice-over commentary for shots of the exhibition and the ongoing events. Set in one of the exhibition halls of the Nationalmuseum's large 19th-century building, the show alternated between shots of the artworks on display, of the audience mingling about as a jazz orchestra provided a musical backdrop, and shorter sequences with interviews, conversations, and humorous skits featuring celebrities, politicians, and those contributing. The show sought to display a sense of spontaneity and "liveness," although not all of the scenes were live and the conversations and events not necessarily as spontaneous as they appeared. Chiefly, the show revolved around a supposed clash between high art and popular entertainment. As Lynn Spigel has noted, a similar approach was also common in US television shows on modern art, where the use of liveness and familiar entertainment forms recurred in presenting modern art to large audiences.41 With regard to museum culture, similar strategies were employed by, for example, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in its early TV project, or later on the Philadelphia Museum of Art with CBS specials starring Barbra Streisand and with the aim of promoting color TV. Spigel highlights how cultural and media institutions joined forces to promote the importance of art and museums as well as the importance of television.42 These examples show how television "provided new ways of looking at art in the context of popular forms [. . .] while it also served as a vehicle for debates about art's greater purpose."43

The Multikonst opening scene takes place on the great staircase in the entrance of the museum, where host Romare accidentally bumps into a museum janitor. Apparently oblivious to the whole concept of an art opening, the janitor is busy putting veneer on one of the exhibition posters mounted on an easel. The two men converse about the word "vernissage," before the merry janitor leaves the scene and Romare introduces two of the project's organizers, Olof Norell of Konstfrämjandet and Gunnar Westin of Riksutställningar.

Host and producer Kristian Romare with actor Åke Grönberg at Nationalmuseum. From the opening sequence of Multikonst—hela Sverige går på utställning (1967). Still image: SVT—Sveriges Television AB.

This introductory skit displays striking similarities with examples discussed by Spigel in the American context. The use of a working-class man as a skeptical character to be lectured by the informed art critic was used by MoMA in its 1950s TV project, where a smoking TV floor manager accidentally shows up on the air with museum director René d'Harnoncourt and an NYU art professor.44 Based on the assumptions that television audiences were skeptical toward both modern art and being lectured by intellectuals, this convention allowed for an indirect way of educating the audience while at the same time making them feel more at ease and perhaps more sophisticated.45 In the same way as in the American example, the Multikonst opening scene was clearly scripted and acted, the "janitor" being played by well-known actor Åke Grönberg, and when Romare corrects his use of the word "vernissage," he does this by casually providing an explanation of the etymological roots of the word. The introductory skit exemplifies the show's overall sense of "edutainment," combining amusement with valuable information. This staged introduction then set the stage for recurrent themes in the following, where several characters took the role of modern art skeptics for the audience to identify with (or object to).

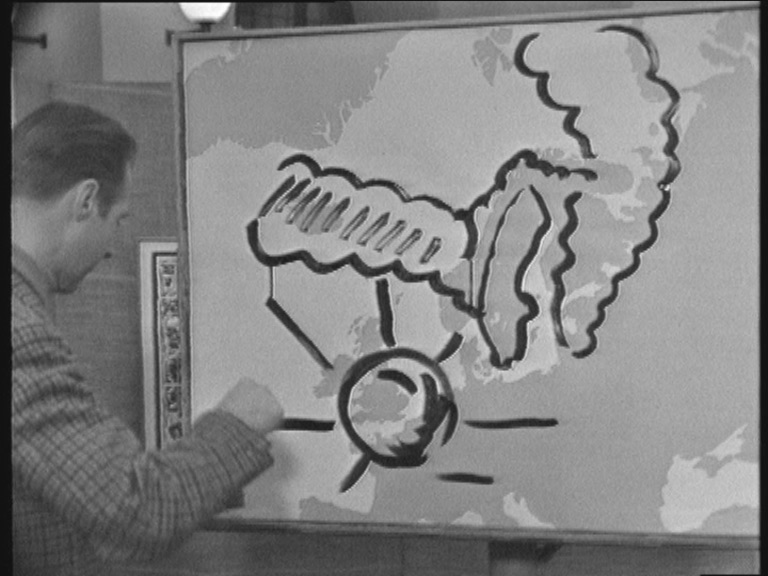

Television weatherman Nils Curry Melin painting a van Gogh-inspired weather forecast. Skit from Multikonst—hela Sverige går på utställning (1967). Still image: SVT—Sveriges Television AB.

Several more celebrity appearances follow. After the opening sequence set in the entrance hall, viewers are introduced to another familiar person: television weatherman and amateur artist Nils Curry Melin. In this scene the theme of the nation is again, and quite literally, at the center of attention. Melin's contribution to the show was described as a van Gogh-inspired weather report, where he, fittingly outfitted with brush and palette, paints a weekend weather forecast on a conventionalized weather chart of northern Europe with Sweden in the center. This humorous scene is followed, in turn, by a comparable but more upfront satirical one, starring actor Stig Grybe in the role of Ante Nordlund from Mobacken. At the time Grybe already had a fairly long career playing the character Ante on radio, film, and television. The appearance in the Multikonst show was structured as a monologue by Ante on the theme of the incomprehensibility of modern art. In the skit, Ante walks around on a small stage, talking about the artworks on display in the exhibition while consistently playing on a supposed clash between center (Stockholm) and periphery (the fictitious Mobacken) as the basis for satirical comedy. The punch lines of the monologue all center on the character as a stereotypical "man from out of town" and his confrontation with the world of modern art.46 However, the satirical edge of the skit is evidently not intended to be toward the countryside populace but rather toward an undefined but clearly big city-based art world and its putative incomprehensibleness. Although the skit pokes fun at modern art as a general concept, several punch lines directly or indirectly are aimed at the artworks on display in the exhibition. This might seem somewhat surprising but can on the other hand be understood in line with the overall theme of the show. In this vein, the skit was based on the assumption that art could be made less intimidating for the imagined audience if framed as light entertainment—or simply as the butt of a joke.

Actor Stig Grybe in character as Ante Nordlund from Mobacken. Skit from Multikonst—hela Sverige går på utställning (1967). Still image: SVT—Sveriges Television AB.

The Ante skit also carried an element of provocation in the sense that it was to be understood as a bit over the top. This was, however, shadowed by a later part of the show. In this scene actor Per Oscarsson is seen engaged in conversation with two of the contributing artists, sculptors Pye Engström and Inga Bagge, and the author Claes Engström. Their conversation revolves around Bagge and Engström's contributions to the exhibit, two small sculptures with explicitly erotic themes. The conversation soon leads up to the usage of what in the aftermath of the event was described as "foul language." The incident led to press headlines, numerous letters and phone calls from viewers to SR, and a public retraction from the head of broadcasting, Olof Rydbeck. The organizers eventually downplayed the "scandal," calling the commotion "more smoke than fire."47 The occurrence, however, was a well-calculated part of the media event. A few months earlier, in December 1966, Oscarsson had made an appearance on the enormously popular talk show, Hylands hörna (Hyland's corner), where he famously performed a strip tease while holding a monologue on sexuality in contemporary society. This event, then, can be viewed as a case in point with regard to the overall ambition of creating a sense of unpredictability and the overall feeling that "anything can happen" in the show.48

The rest of the show featured similarly structured conversations about the displayed artworks, but with less provocative themes. A striking example, which also ties together the theme of national unity with the recurrent mocking of the artworks, took place around halfway into the show. In this scene TV producer, news reporter, and filmmaker Torbjörn Axelman converses with sculptor Berto Marklund on the latter's contribution to the exhibit, an abstract sculpture in pink plastic titled L`accouchement. Axelman admits to being rather unimpressed by the work and announces that they are "going out across the land" to hear from other views on the artwork in question, thereby utilizing what Dayan and Katz have termed the language of transportation.49 Axelman and Marklund then turn to a giant screen mounted on the wall in the room, upon which appears the face of Rune "Bullis" Andersson—a longtime friend of Marklund and well-known sausage manufacturer. In the conversation that follows, Andersson deems the artwork straight-out awful. Following this initial conversation, in interviews with bandy and soccer player Olle Sääw and adman Per-Henry Richter, the two guests express differing opinions with regard to the artworks. At the end of the segment, Marklund himself talks about the intentions behind the work and how it deals with the recent birth of his daughter, something to him both sensuous and beautiful. As he states, the artwork therefore might appeal to midwives.

News reporter and producer Torbjörn Axelman and artist Berto Marklund engaged in conversation through real-time technology with Rune "Bullis" Andersson. Sequence from Multikonst—hela Sverige går på utställning (1967). Still image: SVT—Sveriges Television AB.

Setting aside the actual comments from the men on the screen, the utilization of the large screen itself provided a message. The images of the three men on the screen were transmitted from different parts of Sweden: from Malmberget in the far north, örebro in the central region, and Malmö in the far south. By symbolically tying the nation together through television, the scene explicitly presented modern art as something of importance for the whole of Sweden. In this context, the critical comments about the artwork from Axelman and the three men on the screen might seem somewhat contradictory: the upfront critique delivered by real-time technology can be viewed as a staging of the overall message of Multikonst, namely that it was the individual experience of art that was at the heart of the project. From this point of view, the show provides a number of different approaches toward the specific artworks as well as modern art in general, implicitly and explicitly suggesting that the audience think for themselves and form their own opinions.

However, communication of art by TV was not without implications. According to the overall rationale of the project, simply watching art on TV wasn't enough. This matter was brought to the fore at the end of the show, when Kristian Romare and Sandro Key-Åberg said goodbye to the viewers. This short scene clearly points to the key significance attributed to liveness and a sense of simultaneity. This is evident in how Key-Åberg, appearing for the first time in the show, enters the scene behind a newspaper deliberately displaying an article from the same day about the exhibit and thereby explicitly stating the contemporaneity of the show. Then, among the last words uttered by Romare is a reminder to the viewing audience to go and see the exhibitions. Romare frames this suggestion by referring to the mediation of the television image, outspokenly calling it a "televisual reproduction" and thus implicitly not the "real" exhibition.50 Television made possible the tying together of the nation, providing a sense of unity and simultaneity, but electronic signals could not replace the actual visit to the exhibition and the genuine encounter with the artworks. The ending of the show thus points to a basic premise of television's role and place within the project. It also points to the importance of encouraging the television audience to become an exhibition audience as a vital part of the project.

Engaging the Individual

The task of encouraging television viewers to visit the exhibitions and possibly consume art took on several different forms. At each of the exhibition sites, guests were offered brochures and a special issue of Vår konst (Our art), a periodical published by Konstfrämjandet that contained pedagogical introductions to the exhibit and a range of activities for the audience to take part in, such as questionnaires, study circles, and guided tours. A summary of the overall goals motivating these efforts can be identified in a couple of requests directed to the audience in the official exhibition brochure: following information on motivations for the exhibition and the organizing parties and contributing artists, it concluded, "Think for yourself. See for yourself. Judge for yourself."

These kinds of requests also provided the basis for a contest announced in the opening show. The closing dialogue between Romare and Key-Åberg referenced earlier mainly aimed at inviting the audience to join the contest. The recurrent mocking and continuous questioning of the displayed artworks was part of constructing a prescribed way of partaking in the project. Telling the audience straight out what to think about the art and how to react to it was not considered democratic. Instead, the project aimed toward creating conditions for the individual visitors or viewers to think about and reflect on modern art for themselves. From this point of view, the contest was a fundamental aspect of the project. It was designed as a questionnaire distributed at the various exhibitions locations. The first part of the questionnaire encouraged the exhibition visitors to note which of the displayed artworks they thought most difficult to understand, or, citing the words of the organizers, most "Multikonstifikt." The second part was the actual contest, where the audience was encouraged to note which of the artworks they liked the most and, most important, to provide a personal explanation as to why they chose as they did. The questionnaires were to be filled out and mailed to SR, where a jury would review the choices and motivations and select a number of winners, who were to be awarded with artworks from the exhibition, and, for a lucky few, the opportunity to appear on television.

This contest was also essential for the last of the five programs SR produced in connection to the project. The program, titled Multikonstifikt?, aired a week after the exhibition opening. It was announced as "the audience's own art program" and had an explicitly participatory aim.51 Without the exhibition audience filling out the questionnaires and sending them in, the whole concept of the program, according to the organizers, would have been a failure. This final program, like the opening show, was hosted by Kristian Romare, this time with co-host Katarina Dunér, an art critic who had worked with Romare earlier as member of a panel in the art quiz show Vilken tavla? (1965-1966), which was also the context where the Multikonst project was announced for the first time.52 Multikonstifikt? was a TV-studio production running for just under thirty minutes. The last part of the show was devoted to a filmed visit in the studio of artist Sven X:et Erixson. The main part of the show, however, included conversations with four selected winners from the contest.

Of an estimated 2,500 contributions, ten contestants won artworks they had noted as liking the most. Of these, four were selected to participate in the show. The winner, the contestant ranked number one by the jury, was the first to appear on the show. Introduced in the opening, she is Ros-Marie Andersson, a "farmer's wife" of Norrberga in Ervalla. She reads her winning contribution in voice-over on images of cows in a barn. As is evident from the introductory reading, the cows in the preceding images played an important part in the winning contribution, as according to Andersson's entry, the chosen artwork were to be hung in the barn with the cows. Following this introduction of the winner, the hosts and Andersson converse on various topics related to the exhibition and her experience of it. In line with the project's overall rationale, Andersson remarks on the exhibition's "unusually" large audience and its overall feel as something other than visiting a "real museum." In addition, she comments on where to hang her prize, a color wood engraving by Lars Lindeberg. Although her initial idea was to hang it in the barn near her cows, she instead proposes hanging it in the kitchen, explaining that art you really like should not be kept in the best room with a gilded frame; instead, it should be hung with a more plain frame in the room where you spend most of your time.

Before introducing the next winner, Andersson and the hosts converse on the overall outcome of the contest, and discuss which artworks were given the most votes as "liked" and which deemed most incomprehensible or "multikonstifikt." The hosts take turns reading a selection of personal motivations, and then ask Andersson to guess the contest's results. One artwork that created a lot of confusion for the audience was an object shaped like a small bag, titled "Se på påse" by artist and poet Berndt Petterson.53 As the promotion of the show announced, artworks considered incomprehensible were to be "explained" in the program.54 In place of an explanation, however, a short experimental film by Petterson relating to the play on words in the exhibited artwork was shown.

The film functioned as a transition to the next invited winner. As noted by the hosts, although Petersson's artwork caused some query among the audience, the most questions were raised in relation to a monochrome white print by Rune Jansson. In line with the blunt rejection of an "expert explanation" of the earlier artwork, the presentation of Jansson's work is followed by the introduction of the next winner of the contest, Rune Joneland of Älvsbyn, to describe his individual experience of the work. Joneland then gives a short monologue on a memory of his awoken by the print, when as a youngster working nights at a charcoal stack in winter, he became so overwhelmed by the moonlight reflecting on the snow that he heard music and began dancing. Following this, host Romare introduces the artist Jansson, supposedly to underline the achieved "contact" between artist and audience. Before Joneland leaves the studio space, Romare announces he is getting an additional prize: the opportunity to attend an allegedly sold-out production of Hamlet together with his wife and in company with the artist. The hosts then summarize the exhibition's most popular artworks, leading up to the introduction of the last participating winners: an eleven-year-old girl named Lotta, accompanied by her young friend Eva Maria. In the conversation that follows, the young girls answer questions on their choices of artworks and their written statements in the questionnaire before they are both handed the artworks selected by them.

Judging from the show, the ideal audience of the project consisted of farmer's wives, charcoal-stack workers, and eleven-year-old girls, because they apparently had taken part in the project in the prescribed way. Aside from simply watching the television shows, they had taken time to visit one of the exhibitions, and, guided by the questionnaire, had engaged with the artworks and singled out a selection of objects from the larger collection and related them to personal everyday experiences. The winners further embodied the ideals of the anti-elitist position promoted by the project. There was, of course, nothing coincidental about the choice of winners to appear on the show, something that also highlights assumptions about the target audience. The choice was obviously based on assumptions about class, gender, age, and geography. First and foremost, the individuals appearing on the show implicitly represented all the people not part of the confinements of an established art world circulation. In this sense they all belonged to a category of citizens apparently in need of getting in touch with quality art. However, this is not really the message here. The show's way of privileging individual encounters with individual artworks aimed at showcasing the value and importance of the subjective art experience. The winners represented a more genuine and authentic kind of art appreciation. The design of the show thereby made something personal and subjective a collective and national concern by being exemplary of modern art consumerism. From this point of view, the show can be considered as contributing to the construction of the desired and therefore ideal audience of the project.

Concluding Remarks

The Multikonst project was an event conceived and communicated with and through a variety of media forms. This places the project in a particular historical situation and highlights a number of different relations and interconnections between art, consumer culture, mediated communication, and cultural policy. The project has generally been little researched, despite its conspicuousness and despite the fact that it arguably can be thought of as one of the largest art exhibitions in Swedish history. Instead, the project has, with reference to the occurrence in the opening show quoted earlier, gained a somewhat symbolic position in overall periodization and characterizations of "the 1960s." As I have shown, there are also other types of insights to be gained in researching this and similar kinds of events that I believe can provide, among other things, valuable clues to the ways people perceived and made sense of art at the historical moment.

In hindsight, it seems quite clear that Multikonst, with regard to its scope and utilization of television technology, was something of a one-off event. As is evident in the historical record, by early 1967 television could still be regarded as a new medium and its potential was still thought to be in its infancy. This was soon to pass, the apparent newness soon to be replaced by video, satellite television, and above all, the computer. In the short run, however, the project was followed by a smaller-sized version titled Multi 69, explicitly aimed at kids and youth, but generally, the utopian hopes for art by television were starting to fade. There were of course a number of reasons for this, but interestingly, the waning of these high hopes coincided with the introduction of color television in 1970 and the launch of a second channel in 1969, developments that already in the 1950s were thought to truly revolutionize televisual art education. However, the Multikonst media event taken as a case study—with its peculiar interconnections of technology, consumerism, and state cultural policy—contributes to a historical understanding of ideas and ideals of cultural democracy and art education that potentially adds perspective to current discourses and practice of national public service television as well as cultural policy.

The experimental ambitions of Multikonst were based on utopian aspirations. In hindsight, such ambition toward the future of course tells a lot about the historical situation in which it was voiced. On the one hand, a conception of television as a provider of liveness, unpredictability, and simultaneity was fundamental for the exhibition concept. Television here provided the basic concept of simultaneity and made possible the rhetoric of national unity. In a number of ways, the project shares the attributes of media events, as described by Dayan and Katz, with regard to the "festive" framing, interruptive character, its norms of viewing and participation, its combination of "live and remote," as well as the number of different actors and agendas involved.55 Considered as a media event, the project constructed a virtual exhibition space of national scale, momentary but (at least according to the organizers) of potential historical magnitude. It certainly was, and was promoted as, a High Holiday of mass communication. On another level, however, it is possible to view the project as a way of creating an exhibition that in a literal sense functioned as a routine television show. The exhibits were arranged to reach the public in a familiar environment; the venues were all designed to look the same, and to reach everyone at the same time. In this sense, every Swede was to share a similar experience no matter the geographical location. As an upgraded version of the medium of the traveling exhibition, the Multikonst project was an effort to literally broadcast an art exhibition.

On the other hand, it is evident that television also was considered to have limitations with regard to the overall political context and central aims of the project. The overall goal from the organizers' point of view was to promote and make possible the experience of engaging with original art works. This was framed metaphorically so as to make possible the "contact" between artists, artworks, and audiences. In the case of the Multikonst project, television was used as a means to promote a particular kind of position toward art that corresponded with avant-garde notions of art as part of everyday life and the idea that any ordinary object could qualify as an artwork.56 This view also corresponded with a Social Democratic cultural policy and its ideals of equality and art for everyone, a policy that at same time was aimed at providing work opportunities for artists. In this context, the project was positioned as an experimental and novel way of distributing art objects as well as disseminating ways to think about art in modern society. This position was framed as anticommercial, anti-elitist, and critical toward the art market and the usual business of museums and galleries, which were labeled as far too exclusive, bourgeois, and therefore out of touch with the historical moment. As explicitly stated, it was the unique experience that was of importance, not the unique object or its monetary value.

However, there is also an inherent paradox in the project's attempt to counter one kind of consumerism with another, supposedly better, kind of consumerism. This in part had to do with the overall cultural political context that framed the project, something that also had consequences for the utilization of television. Television was thought to be able to become an important part in the contact-making but never to actually substitute this contact; it could provide information about art, bolster engagement for and create interest in art, but it could never actually be art, because art was chiefly considered a product of an artist's work. The recurrent reminders to the viewing audience of the mediation of television as well as the emphasis on the importance of visiting the actual exhibitions are part of this. Underlying this was also the looming threat of television turning the audience into passive television viewers, rather than active and engaged exhibition visitors. Television was considered merely a vehicle of information on the art and exhibitions, its primary purpose being to encourage the television viewers to stop acting as viewers and instead become exhibition visitors and, in the long run, art spectators. Multikonst was representative of views on television more generally. From the start, the new medium posed a threat to other kinds of activities that were considered more valuable, such as going to museums, reading books, or visiting the theater. Simply "watching television" was not something that SR itself encouraged; rather the opposite. The Multikonst project was thus not just about creating art spectators and promoting good consumerism, but it was also about shaping an active and critical television audience.

I would like to end this article by citing another contemporary art-related media event. Coincidentally, the Multikonst project of 1967 took place the same year as the first international satellite television art auction. This event, titled Bravo Picasso, centered on an auctioning of paintings by the world-famous artist. With the aid of satellite television, bidders from Paris, London, Dallas-Fort Worth, Burbank, and Los Angeles came together in the competition: "Using man's electronic genius to bring you his creative genius," as the show's narrator summarized the event.57 Interestingly, the two events share several similarities in their interlinking of themes concerning art, consumerism, and technology. Both advanced the idea of new technology, allowing for new ways to engage with art through technological virtual space; and in both cases, the engagement in question centered on consumerism and commercialism. Outside of these similarities, there were also substantial differences. The communicative space in the former example was the nation while the latter was global. Essentially, however, the Bravo Picasso event exemplifies the art market commercialism and elitism Multikonst positioned itself against. As Lynn Spigel has noted, Bravo Picasso might be thought of as the first postmodern media event on television: "In Bravo Picasso, the modern ideal of the national museum that houses artists who express their 'nation-ness' gave way to the postmodern concept of an art mart in global space where the real spectacle is not the work of art, but the staging of the sale in the age of satellite transmission."58 In this context of global telecommunications, the Multikonst media event, with its explicitly national and anticommercial rationale, seems almost an inverse of the global art marketplace constructed in the Bravo Picasso satellite event.

About the Author

David Rynell Åhlén is a PhD student in art history at the Department of Culture and Aesthetics, Stockholm University, Sweden. His recently completed doctoral thesis deals with arts programming in Swedish television during the 1950s and 1960s.

Endnotes

1 "Det är en stor glädje för mig att nu med televisionens hjälp i ett och samma ögonblick få öppna 100 lika utställningar på 100 olika platser i landet." All translations from Swedish are by the author. The author would like to take the opportunity to thank the editor as well as the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on the article.

2 Olof Norell, "Om konsten att vara tillräckligt stor," in Multikonst: en bok om 66 konstverk, 100 utställningar, 350 000 besökare, Ragnar Edenman et al. (Stockholm: Sveriges Radio, 1967), 22: "den integrering av medier."

3 "Vår upplevelse av konst har icke med pengar att göra, inte heller alltid med frÅgan om huruvida konstverket är unikt eller mångfaldigat. [. . .] Och det är denna syn på konsten som upplevelse, som svenska staten denna gång önskat understödja."

4 See for example, Dag Nordmark, Finrummet och lekstugan: Kultur- och underhållningsprogram i svensk radio och TV (Stockholm: Prisma, 1999), 206-8; Kjell östberg, 1968—när allt var i rörelse. Sextiotalsradikaliseringen och de sociala rörelserna (Stockholm: Prisma, 2002), 60; Helene Broms and Anders Göransson, Kultur i rörelse: en historia om Riksutställningar och kulturpolitiken (Stockholm: Atlas, 2012), 57-60.

5 Daniel Dayan and Elihu Katz, Media Events: The Live Broadcasting of History (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1992).

6 Dayan and Katz, Media Events, 5.

7 For an overview in English, see Monika Djerf-Pierre and Mats Ekström, eds., A History of Swedish Broadcasting: Communicative Ethos, Genres, and Institutional Change (Göteborg: Nordicom, 2013).

8 Jan Olsson, "One Commercial Week: Television in Sweden Prior to Public Service," in Television After TV: Essays on a Medium in Transition, eds. Jan Olsson and Lynn Spigel (Durham and London: Duke UP, 2004), 250.

9 Olsson, "One Commercial Week", 267-68.

10 Ragnar Edenman, "Konst i offentlig miljö. Kultupolitiskt nytänkande 1959," in Arbetarhistoria: Meddelande Från Arbetarrörelsens arkiv och bibliotek (1996), 70. Originally published in Svenska stadsförbundetstidskrift (1959), 9.

11 Edenman, "Konst i offentlig miljö," 19: "Det är här vi måste sätta in attackerna—men inte med förbud och censurering utan med det självklaraste av stridsmedel; erbjudandet av andra alternativ, andra valmöjligheter."

12 Edenman, "Konst i offentlig miljö," 21: "Att rasera skiljemuren mellan konstnärerna och de stora folkgrupperna, att aktivt verka för en ökad konstförståelse och forma Vår offentliga miljö så att den stimulerar till konstintresse och konstförvärv."

13 For example, during the turn of the century and the early part of the 1900s, the workers' movement campaigned against popular cultural expressions such as film and pulp literature, the Nationalmuseum started to organize traveling art exhibitions, and there were art educational initiatives aimed at schools. Among the important actors were Ellen Key, Richard Berg, and Carl G. Laurin. See Per Sundgren, "Smakfostran: En attityd i folkbildning och kulturliv," in Lychnos: Årsbok för idé- och lärdomshistoria (Uppsala: Lärdomshistoriska samfundet, 2002), 138-75.

14 For an account of this, see Martin Gustavsson, Makt och konstsmak: Sociala och politiska motsättningar på den svenska konstmarknaden 1920-1960, PhD diss., Stockholm University (Stockholm: Ekonomisk-historiska institutionen, 2002), 217-92.

15 Sundgren, "Smakfostran," 138.

16 Statens Offentlig Utredningar 1956:13, Konstbildning i Sverige: Förslag till åtgärder för att främja svensk estetisk fostran avgivet av 1948 års konstutredning (Stockholm, 1956). See also the discussion in Gustavsson, Makt och konstsmak, 315-19.

17 John Durham Peters, Speaking into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communication (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1999).

18 Peters, Speaking into the Air, 24.

19 Peters, Speaking into the Air, 5.

20 Peters, Speaking into the Air, 25-26.

21 See, for example, Fredrik Norén, "Statens informationslogik och den audiovisuella upplysningen 1945-1960," Scandia: Tidskrift för historisk forskning 80, no. 2 (2014): 66-92.

22 Hans Hederberg ed., Är allting konst? Inlägg i den stora konstdebatten (Stockholm: Bonnier, 1963); Ulf Linde, Spejare: En essä om konst (Stockholm: Bonnier, 1960).

23 Peters, Speaking into the Air, 27.

24 SOU 1956:13, 246.

25 Their research focuses on the United States and Great Britain, respectively. See, for example, Lynn Spigel, TV by Design: Modern Art and the Rise of Network Television (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2008); Katerina Loukopoulou, "The Mobile Framing of Henry Moore's Sculpture in Post-War Britain," Visual Culture in Britain 13, no. 1 (2012): 63-81. doi:10.1080/14714787.2011.641785

26 For a more general discussion on the topic of art and early television in Sweden in relation to the genre of "films on art," see Malin Wahlberg, "Från Rembrandt till Electronics—konstfilmen i tidig svensk television," in Berättande i olika medier, eds. Leif Dahlberg and Pelle Snickars (Stockholm: SLBA, 2008), 201-32.

27 The programs were aired in 1967 and 1969, respectively. See Gary Svensson, Digitala pionjärer: Datakonstens introduktion i Sverige, PhD diss., Linköping University (Stockholm: Carlssons, 2000), 104-12.

28 Olof Norell, "Från idé till verklighet," in Ragnar Edenman et al., Multikonst: en bok om 66 konstverk, 100 utställningar, 350 000 besökare (Stockholm: Sveriges Radio, 1967), 37.

29 Dayan and Katz, Media Events, 1. See also the discussion on necessary and sufficient elements of media events, Dayan and Katz, Media Events, 4-14.

30 Dayan and Katz, Media Events, 7.

31 For an overview of the history of Riksutställningar, see Broms and Göransson, Kultur i rörelse.

32 See Göran Nylöf, Multikonst: En sociologisk studie av besökare och köpare (Stockholm, Utställningspubliken, Rapport 4, 1968). In addition, art historian Gunnar Berefelt at Stockholm University conducted an audience analysis later published in Meddelande Från Moderna Museet, a periodical from the Museum of Modern Art in Stockholm. See Gunnar Berefelt, "Allmänheten om Multikonst," Meddelande Från Moderna Museet 27-28 (1968): 6-14.

33 Noël Carroll, "The Ontology of Mass Art," Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 2 (1997): 188.doi:10.2307/431263

34 Kristian Romare, "Multikonst—ett ord, en företeelse," in Multikonst: en bok om 66 konstverk, 100 utställningar, 350 000 besökare, Ragnar Edenman et al. (Stockholm: Sveriges Radio, 1967), 16-17.

35 This is, for example, how he frames the project in a presentation in the TV guide Röster i Radio-TV. See Mats Rying, "Konst över landet," Röster i Radio-TV 4 (1967): 18-19.

36 Romare cited in Rying, "Konst över landet," 19.

37 For a discussion on the origins of this genre of arts programming, see Loukopoulou, "The Mobile Framing of Henry Moore's Sculpture."

38 The first program aired on January 29, 1967; the second on February 7, 1967.

39 Linde, Spejare.

40 See Spigel, TV by Design, 12.

41 Spigel, TV by Design, 44-47.

42 Spigel, TV by Design, 144-77.

43 Spigel, TV by Design, 297.

44 The scene was part of an episode of the CBS public-affairs program Dimension, celebrating the museum's twenty-fifth anniversary in 1954. See Lynn Spigel, "High Culture in Low Places: Television and Modern Art, 1950-1970," in Welcome to the Dreamhouse: Popular Media and Postwar Suburbs (Durham and London: Duke UP, 2001), 265-66. See also note 1, 302-3. See also Lynn Spigel, "Television, the Housewife, and the Museum of Modern Art," in Television After TV: Essays on a Medium in Transition, eds. Lynn Spigel and Jan Olsson (Durham and London: Duke UP, 2004), 349-85; Spigel, TV by Design, 162.

45 Spigel, TV by Design, 161-64.

46 Compare a similar routine discussed by Lynn Spigel, in Spigel, TV by Design, 45.

47 Olof Norell, "Från idé till verklighet," 47.

48 Dayan and Katz, Media Events, 5.

49 Dayan and Katz, Media Events, 11.

50 "Vi har varit på vernissage tillsammans, tack ska ni ha för sällskapet, och nu är det er sak att göra något, till exempel gå på utställningarna. För det vi visar i tv, det är ju bara en tv-reproduktion." Romare later elaborated on this theme in the book Multikonst, where he described the show's aim as to make people "get out of the couch" and "exercise their imagination." Referencing Marshall McLuhan, he also made a plea for artistic experimentation with television. Kristian Romare, "Bilder x bilder—multikonst och massmedia," in Multikonst: en bok om 66 konstverk, 100 utställningar, 350 000 besökare, Ragnar Edenman et al. (Stockholm: Sveriges Radio, 1967), 55-64.

51 "Publikens Multikonst-program," unsigned article, Röster i Radio-TV 8 (1967): 23.

52 The title is a more or less untranslatable pun on words; the literal translation is "Which painting?" but it can also be read as "What a blunder."

53 The title is an untranslatable pun on words, referring to the similarity between the Swedish word for bag, "påse," and that of looking at something, "se på."

54 "Publikens Multikonst-program," 23.

55 Dayan and Katz, Media Events, 5-9.

56 For a more general discussion on this topic, see Jesper Olsson, "Mass Media Avant Garde: Dislocating the Hi/Lo in the Swedish 1960s," in Regarding the Popular: Modernism, the Avant-garde, and High and Low Culture, ed. Sasha Bru (Berlin: de Greuyter, 2011), 445-57.

57 For a discussion on the event, see Spigel, "High Culture in Low Places," 297-99.

58 Spigel, "High Culture in Low Places," 299.