Volume 3 Issue 1 (2013) DOI:10.1349/PS1.1938-6060.A.433

Zoe Beloff in Conversation with Jonathan Kahana:

Mongrel Media and Contemporary Currency --

A Conversation on Brecht, The Days of the Commune,

and Occupy Wall Street

In conjunction with installations of Zoe Beloff's The Days of the Commune, a multimedia project based on Bertolt Brecht's 1956 play of the same name, in Edinburgh (Talbot Rice Gallery, November 2012–February 2013) and Philadelphia (Slought Foundation, April–May 2013), Jonathan Kahana conducted the following conversation with Beloff over several months, ending on Brecht's birthday in February 2013. Consisting of video shot during weekend rehearsals in public spaces around New York City; a performance of the play serialized to take as long as the 1871 Paris Commune; and drawings, broadsheets, and a website, Beloff's The Days of the Commune was mounted in solidarity with Occupy Wall Street (OWS), and often coincided with the spaces and movements of the occupation in Manhattan. In this extended version of a dialog to be published with the Slought Foundation Blu-ray Disc of The Days of the Commune, Beloff and Kahana discuss the origins and sources of the project, its relation to Beloff's previous work, and its place in contemporary anticapitalist art, media, and activism.

Jonathan Kahana: When you first conceived of this project, what was the state of the Occupy Wall Street movement in New York City and elsewhere?

Zoe Beloff: In November of 2011 I was reading a biography of Brecht , where I discovered that he had written a play, The Days of the Commune. I knew right away, even before I read it, that I must stage it. I knew exactly where this must take place, in the streets, starting in Zuccotti Park, which had been cleared of the entrenched protesters by the police only days earlier. I had already been thinking about the Paris Commune; the reason I was reading a biography of Brecht was that I thought that he had a lot to say about what was going on today. I was overwhelmed. Elated because the idea felt completely right, and at the same time terrified by the enormity of the task in front of me.

Kahana: So, at that time, you were identified in what way with Occupy Wall Street ? As someone who lives in Manhattan, who positions herself on the left, and who is also underpaid for her professional and intellectual labor, I can imagine that you were well placed to identify with the movement?

Beloff: Interesting question: am I underpaid? Depends what I am being paid for. As an artist, I work for nothing. I'm outside of the "professional"—that is, commercial—world of art. So I have a day job and I feel very lucky to have one that is, I hope, useful. I teach at CUNY Queens College. I teach practical skills, how to make short films and audio works, how to draw pictures. Right now, as a professor, I consider myself to be well paid. But then again, I spent fourteen years as an adjunct teacher living hand-to-mouth in an illegal sublet, so I know what it's like to live on little more than minimum wage. When I joined in the protest, it was to speak up for friends who can't afford school, who are mired in debt, for everyone who is unemployed.

When the movement began in September 2011, I was so excited. I had been asking for a long time: where is the radical left when we need it? And at last, here it was. I started going down to the encampment, not far from my apartment. Both its idea and execution were remarkable. A town square where total strangers could strike up conversation and discuss ways to change the world. I had never seen anything like that before.

People came to Zuccotti Park for a reason. They had something to say. It was a truly diverse assembly: unemployed factory workers, trade union organizers, political science students, homeless people, radical librarians, anarchist street kids, African Americans and Native Americans crammed into this small space. It was truly festive. I mean this in a serious way. I don't think this is something that we should consider just in the past tense. The grotesque inequalities of our country were illuminated. And this illumination rippled outwards across the country, in the way things are talked about and conceptualized, even now. Not the big changes we would like to see. But one must start somewhere with whatever is possible in the moment.

I don't think it could have happened without the indignados in Spain or the protesters of the Arab Spring I think the economic imbalances all over the world will not be resolved without real change. One could say, what good was the Paris Commune? It did not achieve its objectives, it was utterly destroyed; but I think the ideas that it planted are still rippling outward, and we are listening to them. One of the things that really impressed me about OWS was the idea of leading by example, as did the Communards. Instead of just complaining about inequality, here were people who were sharing books, food, and experiences.

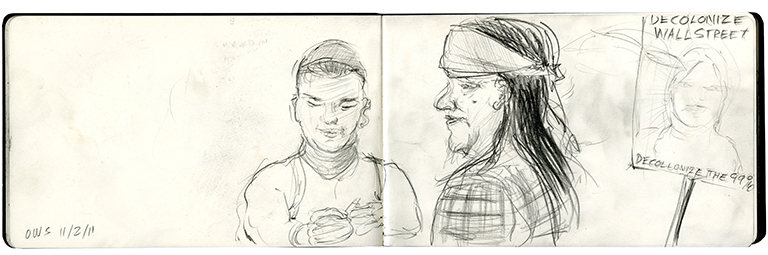

Was I part of Occupy? I'd call myself a fellow traveler, or a friendly witness. I didn't do any organizing. I did not camp out. Initially, my participation consisted of bringing a sketchbook and beginning some documentary drawings. I had never done this before, but I was teaching a drawing class where I asked the students to draw their daily lives, so I thought I should practice what I preached. It was a challenge. I called it "Drawings of Modern Life," a first inkling that I was thinking about Paris in the 19th century and the radical painters of modern life.

Figure 1. "Decolonize Wall Street," Zuccotti Park, November 2, 2011

Kahana: I find your paintings and drawings of the encampment, and also of the Days of the Commune production—perhaps because they lack the precision and banality (or ubiquity) of video—particularly evocative, and very moving. (One can, of course, produce impressionistic effects in digital video: Jem Cohen's beautiful series of Gravity Hill Newsreels about Occupy are one example.) Many artists have given themselves a reportorial or documentary role in similar encounters, so your instinct to reach for the pencil or the paintbrush, and for paper, rather than a small piece of digital technology, is curious and fascinating. What was it about these media that had such appropriateness and urgency to you as a response to these events? Or was there something about the qualities of the digital image that fell short in this instance?

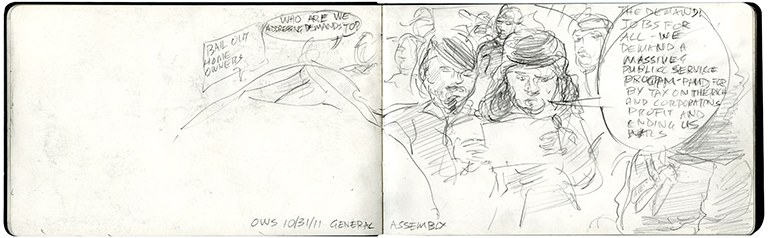

Beloff: When you draw, you become part of something, perhaps because you can't draw everything in front of you. Like writing, rather than recording, you effect a transformation that does not say "this is what happened," but rather "this is my experience at this particular moment." Drawing directly from life, actually being there, is a very odd idea in the 21st century. It is hard to do. I think my hand does most of it. I just feel my fingers tracing over the lines and contours of people's faces. I draw in this way by feeling, like sculpture. It was also a way to quietly observe, look and listen closely over time in a very different way than people with their iPhone cameras or DSLRs. Time is very important in drawing: most particularly where you are drawing a living, breathing, moving world around you. The drawing contains time within it. Perhaps because I come from film, I think about this a lot. I would draw through long General Assembly meetings in almost total darkness when I could barely make out what I was doing. I just tried to transcribe my experience. Only later in the light of subway I would discover what I had done.

For me, digital images of the world arountd us do not say too much. They have a kind of anonymity. Perhaps they scoop up the world too effortlessly, like turning on a microphone without really listening. This is not a problem of technology, but of people who think it will do their work for them. Perhaps when it was harder to take photographs or to film things, people had to think more carefully about what they were doing. When the Communards posed in the Place Vendôme on the occasion of the toppling of the Vendôme column, they collaborated with the photographer. They wanted to speak together to celebrate this important moment, the toppling of a monument to militarism and imperialism. And that thoughtfulness is conveyed to us today.

At the time, I felt conflicted. I had never done this kind of documentary drawing before, precisely because I studied at an art school where the curriculum hadn't changed since the 19th century. So I always believed that sketching was the pastime of Victorian girls—an idea that put me off drawing for decades! And the more I got into my drawings of the Occupy encampment, the more I thought back to Manet, Daumier, and Courbet . And it was actually studying Manet's drawings of the people dying on the barricades that initially led me to start thinking about connections between the Paris Commune of 1871 and Occupy. Since then I have been thinking, is it still possible to be a progressive artist in the 21st century and draw the world around us, or has the form been consigned to the dustbin of history?

Figure 2. "The Demand," Zuccotti Park, October 31, 2011

Kahana: I was reminded of a number of contemporary artists who've used drawing to render urgent, critical events: Sue Coe's sketches of the early days of the AIDS crisis, for instance, or of the Anita Hill–Clarence Thomas hearings; or comix artists like Joe Sacco, who has also drawn Occupy. And among children, of course, drawing hasn't disappeared as a form for making a spontaneous and permanent impression of the world.

Beloff: Children will always draw so long as there are crayons. But is drawing the world around us a form of serious cultural expression? A couple of years ago I listened to a colleague in the art department firmly telling a graduate student that her drawings of the Bed-Stuy [Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn] neighborhood in which she lived were irrelevant to contemporary art. He likened her work to the sentimental social realism of Ben Shahn". It was painful for me to listen to this. Afterwards I felt terrible because I did not confront him. So it stayed with me, and these drawings are a start, a way of practically executing what I didn't say at the time.

I was also inspired by Diego Rivera's watercolors of a boy and his father going to a demonstration, which Rivera did while visiting Moscow in the 1920s. They are like a storyboard, a little film on notepaper. I was thinking of them when I made the small paintings in the final version of the Commune film. It begins as a picture story and sometimes a scene reverts from live action to a colorful storyboard where the actors are now something like comic book figures. Of course I want the answer to be yes, it is still valid to draw modern life. I feel close to popular art forms. I think that comic books and graphic novels can lead the way forward. Although I read philosophy, I do not want to work only for those in the world of high art, but to speak to everyone in a language that is accessible and entertaining. As an artist, I think of myself as a showman.

But to come back to your question, as I spent time at the Occupy encampment, I asked myself, what was the right role for the artist in Occupy? Since childhood, I can't join anything. I am no good at being a party member. It is one of the many reasons that Walter Benjamin endears himself to me: he couldn't join anything either. But that shouldn't get in the way of solidarity or standing with others. On a number of occasions I have been asked, was The Days of the Commune an "official" Occupy project? I find this question strange, since OWS is not a political party. The simple answer is no. I did not ask for money from the Occupy funds. In part, this was because I did not want to get tangled up in bureaucracy, and partly because I felt that as someone with a job, I should dig into my own pocket to support the movement. I just went down to a meeting of the Arts and Culture group and proposed my project. I felt that if I wanted to be "in solidarity" with Occupy Wall Street, I should discuss the project with activists. And they said that since I wasn't asking for money, I could do whatever I liked; and by the way, what was the Paris Commune? As it turned out, people involved in OWS were not that interested in what we were doing. A few of them would stop by in March before or after their meetings in Zuccotti Park, but it was freezing and windy, not so much fun for an audience. I guess I was a bit utopian in my thinking to assume that they would care about our Commune.

Kahana: Let's talk a little more about the other significant sources for this project: the Brecht play, and the locations and process of the performances. What was it about the Occupy Wall Street movement that appealed for a theatrical response? And how did you come to choose The Days of the Commune as the lens or mirror through which to view the days and months of the Occupy Wall Street "period"? It's probably the least well-known and least often performed of Brecht's plays.

Beloff: In my thinking, OWS was itself a theatrical response to what was going on. The encampments weren't simply a place where people lived. The activists choose the most visible locations to live in public and enact together a new egalitarian community. Rather than simply protest, they did something much more powerful: they attempted to show quite concretely that another world was possible. They improvised on the spot a participatory democracy where people shared their resources, where there was enough for everyone, enough food, clothes, free medical attention. Education was free and open to all, including lectures by famous philosophers. It was never meant to be a real city over the long term. It was a proposal for a city yet to be.

The General Assembly meetings functioned in the same way. The activists and everyone who decided to take part each night were trying to do two things at once, to run a city in miniature on one square block, and to change the world. The People's Mic, where the speaker's voice was amplified by audience repeating what they said, was brilliant. Though it was initiated out of necessity—microphones were not allowed—it was nonetheless amazing theater. Here the audience themselves were included in the speaker's words. They were no long simply passive listeners, but participants. And you had to listen and pay attention in order to repeat. The primary form of utterance at the General Assemblies was "we," not "I." Perhaps most radical of all, for the first time we could hear speeches where the vocal performance no longer took precedence. Few people at those meetings could actually hear the speaker, only the content, as the words rippled outwards. There could be no demagogues, no grandstanding at OWS. I would come home from these events elated. I know it sounds crazy, but I felt like if I wasn't there in Petrograd in October 1917, at least I was here now.

So OWS inspired me to do street theater for the first time. In fact, I might say that the street was essentially my project. The concept of the "street" as a site for social change is both historical and completely contemporary. We have only to think of Tahir Square, or the indignados in the Plaza del Sol.

Kahana: But why then did a text, even one by Brecht, seem so central to the project?

Beloff: As I mentioned, it was while drawing the Manhattan encampment of OWS that I began to see parallels between our occupation and the Paris Commune. But even before that, I had been thinking about Brecht. My comic book Adventures of a Dreamer has an episode called "A Brechtian Dreamer" that was partly inspired by his play Saint Joan of the Stockyards. The play explains how CEOs of corporations practice class warfare from above, just like they do now. Reading the play in 2010, I thought it was just as relevant to our recession as it was to the Depression when Brecht wrote it. I was studying his work in the fall of 2011. It was the way in which he constructed a work based on the historical circumstances but used it to ask questions that are relevant today that lifted the Paris Commune out of history and made it contemporary.

Brecht shows us both the point of view of the working people of Paris who decided to occupy their city and the perspective of the men in power, Adolphe Thiers and Otto von Bismarck. He asks us to think about how political and economic forces shape lived experience and to imagine what would happen if a new kind of people's democracy took over a city right now. How could it survive against the forces of global capital? How should it respond to armed attack? These questions address both the Arab Spring and the Occupy movement. Brecht doesn't provide answers. Instead, he invites each of us to think for ourselves. One of the most important scenes in the play, for example, is a short one between Geneviève, the young teacher, now delegate in charge of education who has always stood for peace, and Pierre Langevin, a worker delegate to the Commune. The end is very close now. They are working late at City Hall. They can hear the enemy's guns. They look at the banner proclaiming the principles of the Commune. In 1871 these freedoms were radical; now we take them for granted. But then Brecht has Langevin ask some hard questions:

Freedom of the Individual: Does that include the freedom to make business deals against the public interest; to live off the people; to conspire against the people and to deal with their enemies?

Freedom of Conscience: But what exactly is dictated to them by their consciences? I'll tell you. Whatever their rulers want to be dictated. From the moment a child can walk.

The Right of Assembly: Does this mean that the financial wolves, the parasites of the press, the military hyenas and all the lesser bloodsuckers are free to reassemble the Versailles and use the freedom of Freedom of Speech to publicize opinions of all kinds against us? Is there a guaranteed freedom to spread lies?1

In the end Langevin decides that the people are not yet ready for all these freedoms. They should stick with only one, the right to live. He believes that in times of danger it is only universal freedom that can be permitted. In America we are taught that we live in a free country. But what does that really mean? Brecht shows us that this should lead us to ask some difficult questions.

There are other reasons that the play seemed perfect. Just as Occupy characterizes itself as a leaderless revolution, the play presents a panorama of life in Commune. There are no larger-than-life heroes or sentimental heroines. Instead, it brings to life a small group of working-class neighbors in the Rue Pigalle, Papa and Coco, Babette and Geneviève, Madame Cabet and her son Jean. Together they struggle to make ends meet and learn how to reimagine life in a truly democratic society. It is a world we can recognize and identify with.

Although I admire Peter Watkins's film La Commune, and the fact that he worked with his cast to improvise the dialog, in the end I think it lacks the poetic clarity of Brecht's play. This is something I myself didn't really grasp just reading the text. The language is not naturalistic, everyday speech; but neither is it difficult or ornate. It has a beauty that, even when performed by inexperienced actors, stays with you.

Kahana: And the production had other intellectual sources as well?

Beloff: Conceptually, I was inspired by the work of filmmakers Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, and by the philosopher Slavoj Žižek. The Straub-Huillet film History Lessons was a model for me. It's based on Brecht's story The Business Affairs of Mr. Julius Caesar." The actors wear togas, but they are clearly situated in contemporary Rome, with cars driving past. Žižek explores history in a similar way. In his book In Defense of Lost Causes, he explains (via Heidegger) that the new can only emerge through repetition. The past is not simply what happened. Rather, one must grasp the radical "'openness' of the past itself"—which he says "contains hidden, non-realized potentials."2 It is this idea that is at the heart of my work as an artist.

Kahana: It might not be clear to viewers of the video that the performances are staged all over the city. What's the significance of the various locations?

Beloff: While I wanted to begin performances in Zuccotti Park in solidarity with OWS, I always planned to move on to other parts of the city. The Commune encompassed all of Paris, and I wanted us to share our ideas with New Yorkers in many different places. I toyed with the idea of a tour of the five boroughs but then realized that it was too much to ask the performers.

In the past I had always decided on locations in advance and made sure I had permissions. In this project we winged it. Partly this was force of circumstance: I just didn't have the money or time to start dealing with bureaucracies and million-dollar liability insurance. But I also felt in the spirit of the Commune and of OWS that public space should be free and open to all. I read the guidelines for Zuccotti Park, the ones posted outside the park, and they did not explicitly forbid cameras or theatrical rehearsals. But everyone knew that the security service down there could make up rules on the spot. There was really no way to know ahead of time, if we could perform there at all or if we would get kicked out on day one. My position was that if we were thrown out, we would just decamp to a nearby space and keep going. As a matter of principle, we wouldn't let the authorities stop us.

Figure 3. Still from scene 1

It was important that the locations resonate with the scenes in the play. One of the performers, Joanie Zozike, suggested the community garden at East 6th Street and Avenue B. This became the location for the working people of the Rue Pigalle. Community gardens or allotments are an important part of working-class life in New York, where people who can't afford fancy homes can have their own green space. They are very much in the spirit of the Commune. I loved working here. We could really make ourselves at home. Set up cardboard barricades. It was great for an audience. My colleagues and my socialist neighbors showed up to watch. At one point, I had to run over to an apartment with a stack of broadsheets because one of the garden group really wanted to hand them out at the annual Witches and Wiccans bike ride. Witches and Wiccans meet the cardboard Communards!

I always wanted to stage the big meetings of the delegates to the Commune outside the main branch of the New York Public Library, on 42nd Street, in front of the great Beaux-Arts building with the stone lions. There were also chairs and tables that made it inviting for an audience. The Commune believed that education should be free and open to all, and I believe that the library embodies this idea. But I never thought we would get away with it. The space is owned by the Bryant Park Corporation, which prohibits photography without a permit. My initial plan was to stage one short scene, guerilla style, and see if we could get through it before anyone stopped us. I mean, we were hardly inconspicuous: fifteen people wearing red sashes with pictures of Communards tied to their heads all singing The Internationale" at the tops of their voices. Jokingly, we decided that if security asked what we were doing, Mitch Abidor, who can do an amazing impression of a Frenchman speaking pidgin English, would inform them that the group was actually the "Association des Amis de la Commune 1871," here from Paris for a research trip. But no one said anything. We went back weekend after weekend. On one wing of the library, there was a group practicing fly-fishing techniques. And on the other, the delegates to the Commune held their meetings.

Video clip of an excerpt from Scene 11a

Sometimes I made a direct connection between the location in the play and the equivalent location in New York. For example, there is a scene outside the Department of Education. We staged it outside New York City's Department of Education">, at the Tweed Courthouse on Chambers Street. I decided to present the scene where Bismarck and Jules Favre meet at the opera at Lincoln Center, outside the Met, where a Wagner series was in progress. I knew this was going to be a guerilla action. And indeed, the moment we showed up with Greg Merhten as Bismarck in his trademark spiked helmet, the guards converged on us and threw us off the Lincoln Center plaza. But we just went down to the bottom of the steps, which still afforded us a fine view. It is one of my favorite scenes, a moment of comedy, albeit one in which the leaders of the "free world" discuss the imminent slaughter of the Communards "mit fire und brimstone," while the opera blared from a boom box. People on the street just looked at us.

Figure 4. Still from scene 10

I very much wanted to shoot the scene of the bourgeoisie in flight to Versailles at Grand Central Station. It would have been great to see them hightail it to Westchester. But I didn't dare. Instead, we shot the scene underneath the Manhattan Municipal Building opposite City Hall, where the bourgeoisie were forced to flee by subway.

In the final scene, the bourgeoisie watch the destruction of the Commune from the ramparts of Versailles. The boardroom of the JPMorgan Chase bank would have topped my list of locations, but unfortunately I didn't have access. So I decided on Governors Island, which is right off the tip of Manhattan, with a great view of the city. It also has an old fort with cannons dating back to the Civil War. When we all went out on the ferry, there weren't just twenty-two Communards in full costume, but also a whole crowd of Civil War reenactors. I had to tell everyone not to get mixed up and end up in the wrong conflict. You can hear shots from the reenactors' rifles on our soundtrack while helicopters circled overheard. It was perfect.

Kahana: In the case of Zuccotti Park, where most of the performances are staged and filmed, one could say that the space itself has a very different significance for the protest movement by the time you start working there in the spring of 2012. For two months in the fall of 2011, the park is an encampment for protesters; Mayor Bloomberg "clears and restores" the park in November, and a judge upholds the city's claim that the First Amendment doesn't protect the protesters' camp. The protesters are then forced to take a different sort of ritual disposition to the park, leaving and returning daily. Was the regular but intermittent nature of your own time in the park with your cast a way to match this rhythm? Or did you think of it, rather, as a way to memorialize the two-month occupation, and the sense, in the fall of 2011, that the occupation might go on indefinitely?

Video clip of an excerpt from Scene 3c

Beloff: I wanted to start in Zuccotti Park to align ourselves with OWS, but I didn't think specifically about matching their rhythms. From the start, for example, I realized that we could only work on weekends, as too many of the cast had day jobs. Given our lack of resources, rehearsal studios, money, time . . . this was the only way the project would have worked. But I also believe it was the right way to work, so as to include as may people as possible.

I had the idea for the project in late November 2011, but it took time to prepare and assemble the cast and crew. It came to me that we should do the play on weekends from March through May: the same brief period that the Commune existed. We would map our time over their time. I think it is important that this is a work over time. You see the seasons change: at first, everyone is blue with cold; and at the end, it is summer. You can see how we all learned on the job and the performances at the end are a far cry from those first days. Building a social movement takes time and work. The project makes this visible. In a certain sense, it is a document of a certain time in New York in the year 2012.

Kahana: How was your company of actors assembled?

Beloff: Just as the Occupy encampments could be thought of as a rehearsal for a new, more democratic society, where the actors are ordinary people, so it was essential for me that the cast of The Days of the Commune represent all New Yorkers. I put out a call for a band of performers of all ages, gender orientations, ethnicities, accents, shapes, and sizes on Occupy Wall Street's Performance Guild listserv, and on bulletin boards at downtown theaters. The only requirements were enthusiasm and a loud voice. Actors, activists, and artists answered my call. At the beginning there were thirteen performers. But, like any movement, it grew and changed. I was constantly rounding up new people. I think there were around thirty cast members in all. Some people joined us for a weekend or two, others for the whole three-month period. Every performer played multiple roles: one character was often played by several actors, since not everyone was available at the same time. For example, Papa was played on Saturdays by Michael Paul Britto and on Sundays by Pietro Gonzales. This was one reason performers wore the name of their character around their neck. Actors who played actual historical figures wore pictures of them drawn on cardboard and tied to their heads; this was also a gesture toward the signs worn by Occupy protesters.

Scheduling was a nightmare. On Friday, someone always got sick. So actors were thrown into parts in the very last moment. There are scenes with tough French working-class women played by CUNY professors who had no acting experience but were very brave, and threw themselves into it.

I told performers to familiarize themselves with their lines. I felt that asking them to learn lines by heart was too much to expect, but gradually some actors started to do this anyway, and the others were impressed. They watched the scenes online and were inspired to memorize their scripts and improve their performances. I made it clear at the auditions that there is no room for prima donnas in the Commune. Everyone was going to have to play parts small and large and take turns holding the props and banners. And that's what they did.

Brecht said that even a donkey should be able to understand his plays, and he kept a little wooden donkey by his desk to remind him. I always think that my work should, on some basic level, be enjoyed by children. I wanted The Days of the Commune to be a great colorful pageant, so the costumes and the props were very important. And let's not forget that it is a musical. One of my first ideas was that we would begin each session with a song, because songs bring people together and attract attention. Even the police guarding Zuccotti Park enjoyed Hanns Eisler's songs and music.

Video clip of "Einheitsfrontlied" sung before scene 11c

Kahana: It's clear that your actors come from a range of backgrounds, professionally speaking: some of them have trouble with their lines and the physical aspects of performance. (That some of them play more than one role, without caring or being able to inflect the roles in ways that distinguish the performance of one from the next, makes it even harder for the audience to ignore these material constraints on mimetic representation.) But they seem remarkably patient with each other, and—as I saw on the East Village community garden "set"—you with them. What was it like for you to spend several months working with each other?

Beloff: It was amazing and totally nerve-wracking as well. I felt very responsible for making sure that everyone had a good working experience. Two of our original cast quit. One performer left early on because he said we did not engage in enough discussion or spend enough time interfacing with OWS. To boot, he quoted one of Brecht's learning plays (Lehrstücke) that he felt justified changing one's mind. I felt terrible. But given that we had only had three hours together each day, my thought was that we would simply never get through the play with lengthy discussions, and the other performers agreed.

The good thing was that this defection set off another round of casting. Everyone was great about contacting friends and fellow actors. Jay Dobkin from the Living Theater and his wonderful daughter Miranda joined us. I got up courage to ask Greg Mehrten, another very experienced actor, to participate. He ended up playing the Commissionaire, Bismarck, and Rigault. Many of the performers were incredibly dedicated. Ahuva Willner came all the way from Baltimore to play a variety of roles every weekend. She was the only person who had camped out at an Occupy site last year. The cast grew as we went along. Experienced actors knew from the start that they would be working with nonprofessionals. But everyone was improvising as they went. In the scene that you saw, Jay only discovered the day before he was to play Coco because our usual Coco couldn't make it.

As a director, I have always worked to shape performances with my actors. Here, again taking my cue from the Occupy meetings, I saw my role more as instigator and facilitator. I felt it important to respect what the performers could bring to the work—if not as actors, then as New Yorkers. As director, my role was organizational: I decided how much of the play we could work through in a session, decided on a location, prepared some very basic blocking so people would know where to stand and move. I sketched this out ahead of time and went over it with the cinematographer. But I told the performers from the start, "Occupy your characters," and they did. Occasionally I would intervene to explain something in the text or to tell people to speak up. But I did not correct them if they came out with a horribly mangled French word. After all, we were not in France, and I didn't want to be a schoolteacher. In our Commune, people were free to pronounce things any way they wanted.

I also knew there would be a collage of styles and embraced them all, everything from broad theatricality to bare line reading. Papa as played by Michael Britto on Saturdays was a very sweet man, while Papa as played by Pietro Gonzalez on Sundays was a tough guy. They embodied two sides to the character. It was a whole new way of thinking about performance. Joy Kelly studied the Black Panthers for her role as Varlin.

Kahana: And along these lines, some of the actors' timing is particularly eccentric. I began, while watching the performances, to understand this awkwardness as a kind of collective gestus, a question that the production was raising about its own historical timing, vis-à-vis the Brecht play, or Brecht and Eisler's use of the Commune and the 19th century as a point of reference, or even about the timing of the production itself—staged on the weekend, after all—relative to the work week, during which, I assume, many of the actors were preoccupied with what we call "day jobs." (The presence of scripts, from which many in the cast were reading their lines, started to look to me like a reminder of this larger problem of the time or rhythm of artistic production, and it was interesting to see the scripts occasionally or gradually disappear from the actors' hands.)

Beloff: Your question reminds me of the work of Walter Ruttmann, his audio work Weekend, or, indeed, his film Berlin: Symphony of a Great City, which are very much about the rhythms of the workday. And of course these rhythms have only accelerated and grown crazier in New York in the 21st century, where everyone is desperately trying to make ends meet and has an insanely busy schedule. Our stock member of the bourgeoisie, Tony Lewis, never seemed to take a day off. He would show up for performances well dressed in an elegant suit and tie to play the Corpulent Gentleman and was all set to rush back to work as a heath-care administrator after our shows. All he had to do was take off the top hat. I wish more of the cast and crew had listed their day jobs in their biographies on the website—waitress, car park attendant, office manager—because that dual existence is the reality today if you want to be an artist. And we as artists are all too often ashamed of it.

Kahana: Of course, the viewer is also invited to enact this kind of temporal disjunction in noticing that many of the actors have only half a costume: a blouse or jacket appropriate to the play's historical setting, say, paired with jeans and sneakers. Was there much discussion of this aspect of the historical effect?

Beloff: As I said, I thought of the play as a pageant. So costumes were important to attract attention and lend a festive air to the performances. From the start I didn't want to create perfect replicas of 19th-century costumes even if I could have afforded to. This was the past erupting into the present. Every character was both a contemporary New Yorker and at the same time a 19th-century Parisian, and the costumes like everything else should reflect that. I started by studying photographs of the Communards. It was actually an incredibly well-documented event, just like Occupy itself was. There are portrait photographs of almost all the delegates to the Commune. They were well aware of the historical importance of their actions.

So having studied the historical costumes, I did a series of small paintings of the principal characters to define a look and a color scheme. I was lucky to have a very experienced costume person, Ericka Munro, who did amazing things with $2,000. She created an incredible number of costumes. She made some of them from scratch, like the women's striped skirts. The rest she found in a giant thrift warehouse in New Jersey and then altered them appropriately. We discovered remarkable connections between the 1870s and the 1970s, like macramé shawls. Berets from Catholic schoolchildren were turned into the sailor hats for the tough Communard women. Army surplus coats got new red trim applied with a glue gun.

Each performer decided how to wear his or her own costume. Sometimes, I had to stop myself from commenting because strange things did happen. A working-class woman dying on the barricades wore fetching eye shadow and a velvet choker. Sometimes new interpretations of the characters erupted: I asked Michael Paul Britto to wear black to play the procurator of the archbishop of Paris in conference with the governor of the bank of France, and he arrived in a black hoodie and jeans. Along with the fact he wore a large gold cardboard cross on a thick gold chain he got from a hardware store turned him into a hip-hop priest.

Figure 5. Still from scene 7c

My idea for creating all the props and scenery out of corrugated cardboard came from observing the Occupy encampment and, of course, from going on marches. Cardboard is the medium of protest. I was also thinking of one of my favorite contemporary artists, Thomas Hirschhorn, who makes all his installations out of cheap materials like cardboard, packing tape, Styrofoam, and all the detritus of modern life. I really admire his amazing combination of philosophical and political astuteness, playfulness and visual inventiveness. It was also an enormous task making all the props. Having never done this before, I had to find a new visual vocabulary. How to paint a cardboard cannon or a dead rat? How big should they be to read clearly for an audience?

The most difficult objects to deal with were the rifles. They are very important in the story: Phillipe and his brother François Faure have an armed standoff; the National Guardsmen carry rifles. I made some out of cardboard, and I realized that from a distance, they look quite realistic. In New York is it illegal to carry fake firearms, even if they look like toys. We had enough problems at Zuccotti Park without getting arrested for fake guns. Then suddenly the day before we were to do the performance, I had an idea: I would bolt the guns to blue backing cardboard so that they would be pictures of guns, not fake guns. And the police bought this semiotic distinction. You can see them checking us out in scene three, but they didn't say anything and the actors just kept going.

Figure 6. Still from scene 3e

Once I started with cardboard, I had to keep going. The film begins with small paintings of OWS and then the Siege of Paris [September 1870–January 1871]. I could have used documentary video and historical photographs, but I chose not to. To use documentary images, apart from the fact that it is a cliché, implies that we have some kind of unmediated access to history, that these images impart a kind of truth to the text.

Kahana: Or perhaps it implies the inverse: that the play is just (a) play? Which is not necessarily to say, of course, that it has no documentary function.

Beloff: This demarcation of the limits of historical memory is, for me, a way to create not a nostalgic turning back, like conventional costume drama, but rather an abrupt and forceful eruption of the past into the present. I don't believe in an unmediated access to the past as though the history was a fixed entity, like a movie with a single storyline. In fact, I wanted to show just the opposite, that we invent the past as we speak of it. The past is just a picture that we ourselves create, and this picture is as much about us as it is about those long dead. The little paintings, like the costumes and the performances themselves, inscribe a gap between narration and image, what is said and what is shown. Our performance is no more than a storyboard waiting to come to life. Not a replica of something that once was, but a sketch waiting to be fleshed out, a new Commune waiting to be realized.

People asked me again and again, what were we doing, a piece of street theater or a film or what? My feeling is, why choose? Why is that a question? I'd say, all of the above. Today everything needs to be visible in the real world and in the virtual one, local and international. Actually, one of the most productive ways of getting our ideas out was simply to hand out broadsheets, a publicity technique much used by journalists during the Commune. We handed out a couple of thousand.

Kahana: When the newsboys appear, Brecht stages a sly moment of conflict, internal to the play, between the media that speak for the bourgeoisie—the newspapers, whose headlines, as shouted by the newsboys, warn Parisians against voting for the Communards—and the medium that speaks about this bourgeois media strategy, the play itself. And the appearance of this kind of immanent media critique, which you shift slightly to address us in our own time (Le Figaro becomes the Wall Street Journal, Le Moniteur is the New York Post, et cetera), made me want to ask you about the value of the play and of its production—of the form of theater, and the various pre-electronic media forms that figure in the play—for a critique of the media worlds of the present. You're staging the production, after all, in many different media at once, across many different platforms . . .

Figure 7. Still from scene 5

Beloff: I thought of the play less as a "play" than as a script, and most importantly as structure to build our event around. I thought of Brecht's writing as an intellectual scaffolding. That's it. At the time we were doing the performances, I thought to myself: suppose I did have access to a theater, would I go for that? And the answer was no, I did not want an actual theater. It would have made no sense to me. In part, yes, the setting would have been too bourgeois. Then the play would have been just a play and would have been judged according to very different—and to my mind, irrelevant—artistic criteria: was it well acted, coherent, and so on?

At one point someone asked me if I would stage a scene in a gallery where some kind of art/OWS discussion was going on. I said no. I did not want to bring my band of performers indoors in front of a sit-down audience. I felt that we would be judged according to "professional" acting standards and not taken seriously because what we were doing was really, honestly just a rehearsal. I am not saying I couldn't bring the piece indoors, but I would have to really think about new strategies and more rehearsal time. Outdoors the performances weren't really theater so much as a rabble or crowd just acting up. I think for people who stumbled upon it, the whole thing was so surprising that its primitive production did not distract from the idea of the piece.

I was just thinking about the forms of media that are our contemporary currency in the language of protest, demonstrating on the street and putting those images and sounds online. I wanted to make something ultimately that was not media specific, that could travel in different ways, from the street, to a cinema to a gallery, or indeed could be viewed on someone's phone. People kept asking: what are you doing? A film, or a play, or what? I was thinking: why choose? Why not all of the above? Call it "mongrel media."

Kahana: Thinking also of your work on the Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society,3 I was wondering how the amateur figures in your thinking about utopia. And the Communards: are they also amateurs?

Beloff: As I have said, I don't make my living doing art, so I count myself as an amateur. And to answer your question, I feel strongly about championing the amateur. My installation Dreamland: the Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society and its Circle, 1926–1927 was all about the idea that ordinary people can take on difficult intellectual concepts and use them to change their world. It began a few years ago when I was invited by the Coney Island Museum to create an exhibition to celebrate the centennial of Freud's trip to the amusement park in 1909. Instead, I decided to focus on his legacy, the unconscious of the people who lived, worked, and played at Coney Island after his visit. The Amateur Psychoanalytic Society was my framework. My exhibition included a wide range of media, drawings, lecture notes, objects, and even "dream films" made by members who reenacted their dreams on film. It was an imaginary archive, yet it grew out of an enormous amount of research. I call it a serious history, just not a literal one.

In the early part of the 20th century, Coney Island was a hotbed of socialism. I proposed that the society saw psychoanalysis in the same utopian spirit, as a way to change their world. Just as socialism would free people from oppressive conditions of labor, so psychoanalysis would inaugurate an intimate politics of desire. I think of the members of the society as visionaries, who, undeterred by lack of finances or professional training, decided to explore their inner life, to share their dreams with each other, and in doing so attempted to free the psyche from the constraints of cultural and sexual mores of their time. I think of the Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society as something that might have existed and might yet exist, a potential for people to start their own such societies.

The Coney Island project set me thinking seriously about the idea of utopian societies, and I wanted to do more work on the subject. I think of the Communards, in spirit, as the grandparents or the great-grandparents of the Coney Island Society. They were not professional politicians. They were journalists, engineers, artists, and tradesmen. They came from a wide variety of backgrounds. They decided they needed a new form of government and then set about organizing it themselves.

Kahana: Brecht uses character and narrative in what we could call—perhaps anachronistically but not, I think, inappropriately—an "interactive" way. It's not just that the narrative of his stories is organized to serve the will and interest of the characters who populate it, and whose inner lives the narrative exists to fulfill—this is how the two work in the bourgeois novel, where the narrative seems to "belong to" the characters—but also the other way around: the question of "whose" story it is is hard to answer, from one moment of the narrative to the next. The characters and the narrative—this is particularly the case, I think, in the short historical allegories in Tales from the Calendar [Kalendergeschichten]—sometimes operate independent of each other, or in a double-jointed way, one capable of throwing the other off its rhythm, keeping the reader constantly guessing about where the story would go or end. This seems to be part of the point of Brecht's allegorical work with history; and I wondered whether this might also be true of your thinking about Days of the Commune and its relation to the historical events of the Occupy movement—with which it was, of course, a nearly contemporaneous production. For one thing, the performers in your production frequently move, as you've said, from one character to another; and the characters themselves then change as different performers take them on, according to their schedules. As well, one could think of your Commune as an allegory for OWS, but one taking place at the same time as the event it allegorizes: allegory as an interpretive structure being constructed for an event as it is unfolding.

Beloff: In Tales from the Calendar, Brecht's stories throw one off balance. The characters are conveyers of ideas. I think filmmakers like Alexander Kluge and Fassbinder are the inheritors of this form, in their work. Their characters are quite blunt. I've really admired Fassbinder's work since I was a teenager. When I think about it now, the way he kept working with the same actors across films means that when you see them, they are both themselves, his loyal troupe of oddball performers, and characters; and you read these two things simultaneously—the actor is not subsumed into the character. I really like that in his films.

But I think you give me more intellectual credit than I deserve. I was not thinking: I am making an allegory. I was just trying to get through the performances as best I could. But it is true that I was inspired by the structure of OWS; it gave me permission to work the way that I did, and certainly lit a fire under me to get this done, no excuses. I was thinking about what we were doing as another form of OWS in action. Just the very fact of raising questions about how we might want to organize our town. What is important to us?

I recently showed some scenes as part of a talk I gave in Berlin. Afterwards an artist who grew up in the GDR said it was amazing for her to see us all singing Hanns Eisler's songs—just because we wanted to, in New York in a radically different context than the one in which she had sung them as a child. So things move through history and take on new and different meanings.

Kahana: One of the things about this project that's particularly fascinating is that it's quite difficult to say where and when it's a rehearsal for a performance rather than a performance. Do you think that this is because, like some of your previous work, it's really more about training than about what we usually mean by effective action?

Beloff: I did not want to train people to be actors in The Days of the Commune because that implies that they were no more than raw material shaped or molded to a prearranged idea. Yes, that sense of training is quite important to some of my previous work, like my film installation The Infernal Dream of Mutt and Jeff.4 That piece is based on two artless instructional films from the 1950s: Motion Studies Application, which explains how to optimize the motions of a worker on the assembly line; and Folie à Deux, one of a series of films on how to identify, but not treat, a mental disorder. In both films, people are treated as no more than objects, as bearers of motion; and I realized that the films were really two sides of the same coin, the presentation of the productive and unproductive body. But that's a very different sense of bodies in movements than Brecht and I are working with in The Days of the Commune.

Figure 8. Still from The Infernal Dream of Mutt and Jeff

Of course I wonder a lot about what Brecht would have thought of us, the ragtag Commune. He considered a minimum of six-month rehearsals essential for his productions. The trouble is that training implies a master. I do not want to be in that place. For me, rehearsing is about doing something again and again; each time the group struggles to work together better. In the course of rehearsing, we have to pay attention to each other.

I believe that politics itself is not about teaching but learning. Brecht wrote learning plays, Lehrstücke, not teaching plays. The Days of the Commune was a structure to think with and through. At the end, as the working people are dying on the barricades, Geneviève Gericault says that they have made mistakes, but they are learning; to which Jean Cabet says, what is the use when you will soon be six feet under? And Gericault responds, "there is more to the world than just us." And that is how I feel: we carry their struggle into the future.

Though the Paris Commune grew out of historical circumstance very different from our own and only lasted three months, I do not think it was a failure. Those working people of Paris lead us by their example, precisely because they did something for themselves that seemed impossible. They were not afraid. They created a potential. Writing about revolution, Žižek quotes Samuel Beckett, "'Try again. Fail again. Fail better.'"5 Only half joking, I say that this could have been our motto as we all struggled to work together to create better performances. There is no line between rehearsing and performing. It is all a rehearsal, a work in progress.

About the Author

Zoe Beloff is an artist and professor at Queens College in the departments of media studies and art. She works with a wide range of media, including film, projection performance, installation, and drawing. Each project aims to connect the present to past so that it might illuminate the future in new ways. She is currently exploring utopian ideas of social progress. Her projects have been presented internationally at venues that include the Whitney Museum of American Art, SITE Santa Fe, the M HKA Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Jonathan Kahana is associate professor of film and digital media at the University of California–Santa Cruz, where he directs the Center for Documentary Arts and Research. He is the author of Intelligence Work: The Politics of American Documentary (Columbia UP 2008) and the editor of The Documentary Film Reader (forthcoming from Oxford UP). His current research—toward a book called "Going Through the Motions: Talking Pictures, Reenactment, and the Work of the Past"—focuses on the artistic, cultural, scientific, and political uses of historical performance.

Endnotes

1 Bertolt Brecht, The Days of the Commune, trans. Clive Barker and Arno Reinfrank (London: Eyre Methuen, 1978), 80.

2 Slavoj Žižek, In Defense of Lost Causes (Brooklyn and London: Verso, 2008), 141.

3 Zoe Beloff, ed., The Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society and its Circle (New York: Christine Burgin Gallery, 2009).

4 Zoe Beloff, The Infernal Dream of Mutt and Jeff (Sheffield: Site Gallery, 2011).

5 Žižek, In Defense of Lost Causes, 210.