Volume 1 Issue 1 (2008) DOI:10.1349/PS1.1938-6060.A.289

Qu'est-ce qu'une madeleine interactive?:

Chris Marker's Immemory and

the Possibility of a Digital Archive

Erika Balsom

I dream of a world in which

every memory will create its own caption.

--Chris Marker

Rebecca Comay writes,

The archive, whose very name evokes the language of origins and the promise of mastery-in its double etymology arché famously signifies both "command" and "origin"-confounds every beginning and every rule. If the aporia of the "heap" turns out, in every case, to be the straw that breaks the camel's back-the camel in this case being the dream of narrative consistency, and thus the very possibility of history-writing as a sequential temporal and logical ordering (before and after, cause and effect)-this leads us to the startling conclusion that the archive, condition of possibility of remembrance, exceeds and confounds the time of history. The collection, source, and reservoir of recollection, is itself suspended in the immemorial. 1

Here Comay approaches a problem central to a theory of the archive: how precisely does one determine when a set of items becomes a collection, an archive? At which point do the grains of sand from Beckett's Endgame become a heap?2 The sequential ordering of the archive immediately confounds its organizer as "grains of sand" accumulate and resist recuperation into a tidy pile. Linear, historical time, when transposed to the operations of archivization, manifests itself in the form of arbitrary yet rigid classificatory systems, none of which preserves the fluidity and dynamism of meaning of that which has been archived. Despite the etymology of the word, giving the archive a mandate that is at once nomological and institutive, to localize the exact origin of the archive proves to be an insurmountable task as it becomes impossible even to distinguish whether the memory or its inscription as archive came first. The archive exists as the very possibility of remembrance, but simultaneously there must be a memory or event for the archive to take as its object of preservation.

The hope for a perfectly systematized and complete archive has found its way into film practices such as the early work of Peter Greenaway and the Magellan cycle of Hollis Frampton, but similarly figures as an important trope in much conceptual art, as is evident in Bernd and Hilla Bescher's photographic series of industrial architecture, the work of the Art and Language collective, and others. Frampton's unfinished Magellan cycle put forth the impossible task of constructing an entire metahistory of film, from the medium's beginnings in photography to its challenges by the digital, thereby showing the fracturing and disintegration inherent in any attempt at total archivization. Gerhard Richter's Atlas (1964-present) similarly constitutes the artist's personal archive, self-reflexively referencing an entire body of work and underlining the impossibility of a perfect archival ordering. Richer has intermittently added photos to his Atlas since its inception in 1964, with the result that it now is comprised of over five thousand photographs and six hundred panels. The source material is drawn from disparate places: amateur photographs, magazine and newspaper clippings, pictures of historical personages and events, pornographic imagery, sketches for installation plans, and other documents referring to the artist's work contemporaneous with the moment of production of that particular section of the archive. Such heterogeneous material guarantees a hybridity that points to a fundamental instability in any conception of the total archive. Richter's collection of imagery is not recuperable into an easily understood rubric or classificatory system as the archive makes no claims of comprehensibility and definitiveness. The archive, as it is taken up in contemporary art practice, both promises the perfectibility of taxonomic order and simultaneously demonstrates its failure. The great hope of the archive is that its object will fit its order without exception, but the artist's archive tends to highlight blockages and failures, the sites at which archivization is brought to points of crisis or internal contradiction. This crisis of the archive is precisely what is at stake in Comay's assertion that the archive "exceeds and confounds the time of history." That is to say, the archive rests on a certain aporia as its promises of mastery and consistency are necessarily compromised by the chaos of objects in the world, resistant to the violence inherent in attempts to fulfill taxonomic order.

What, however, are the new archival possibilities afforded by the increasing ubiquity of digital technologies? Digital media, with their dematerialization of information submitted to the modularity of the discrete segments of binary code, would seem to further fracture the archive when compared to the relative continuity of analogical media, giving way to a fundamental loss of the archival object as it is dematerialized into information. Hal Foster writes, "Is there a new dialectics of seeing allowed by electronic information? ...Art as image-text, as info-pixel? An archive without museums? If so, will this database be more than a base of data, a repository of the given?"3 Without question, a certain loss does accompany the digitization of the archive and this paper does by no means intend to celebrate unproblematically such a development by arguing for the capabilities of digital media for archival storage. Rather, when one considers the particular difficulties met in conceptualizing the archive with regard to a tradition of historiography as "sequential and logical ordering," the possibility of a digital archive seems to provide a method of transmission perhaps more suited to the characteristics of the archive itself, providing a more rhizomatic and shifting structure that would be more able to create transversal linkages, mnemonic associations, and greater interactive possibilities for the user. Such a structure is not proposed as a replacement for the storage capacity of the traditional archive, but rather as a strategy perhaps to understand it better through an exploration of the alternative possibilities of transmission of archival documents afforded by digital technologies. The answer to Foster's question is a resounding "yes": the digital archive becomes more than a mere database of pre-given objects, changing the way the user experiences the archival object and offering increased possibilities of interactivity.

*** ***

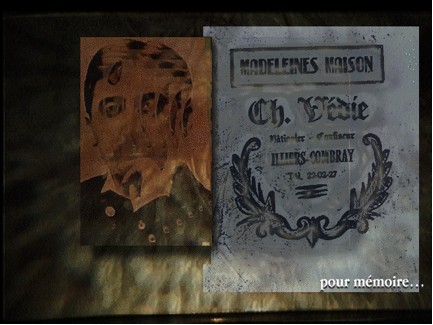

Chris Marker, an artist and filmmaker known for his unceasing preoccupations with memory and its relation to the image, has attempted to put such a theory into practice with his 1997 CD-ROM, Immemory, produced for the Centre Georges Pompidou. Immemory was the first in a planned series of artists' CD-ROMs all dealing with the theme of memory and was first shown with the title Immemory One, allowing for the possibility of subsequent versions to be produced. Produced using Hyperstudio, the work contains a small number of sound and video clips, mainly due to the limited data storage capacity of CD-ROM technology. Continuing the thematics of his earlier work across various media (particularly his best known works, 1962's La Jetée and 1982's Sans Soleil), in Immemory, Marker declares, "I claim for the image the humility and powers of a madeleine." Here Marker draws from Marcel Proust's A la recherche de temps perdu, in which a taste of the tea-soaked biscuit spurs the narrator's mémoire involonaire of his Aunt Léonie's house at Combray. Proust writes,

But from when a long-distant past nothing subsists, after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, taste and smell alone, more fragile but more enduring, more immaterial, more persistent, more faithful, remain poised a long time, like souls, remembering, waiting, hoping, amid the ruins of all the rest; and bear unflinchingly, in the tiny and almost impalpable drop of their essence, the vast structure of recollection.4

Marker extends Proust's original formulation that "taste and smell alone" were capable of triggering involuntary memories, writing that, "Thus one comes to call Madeleines all those objects, all those instants that can serve as triggers for the strange mechanism of Memory." Marker utilizes the new possibilities afforded to him by the employment of a CD-ROM interface in order to explore the connections between the image, memory, and the archive. Much of the critical writing on Immemory treats the project primarily in terms of its thematics, common to Marker's oeuvre, and foregoes any attempt to demonstrate the ways in which such thematics may be affected through the use of a CD-ROM.5 This paper seeks to theorize what is at stake in Marker's embrace of new media, specifically in the spatialization of memory into an intensive trajectory, decided upon by the ambulatory movements of the user, and in the relation between technology, memory, and the archive.

Marker's utilization of the new media format of CD-ROM as a way to explore memory and its archivization offers a sharp point of resistance to certain cultural theorists who see new media as inherently incapable of representing either private or collective memory. A key representative of this tendency, although by no means the sole, is Paul Virilio. Throughout his oeuvre, Virilio sees contemporary society, with its accompanying technological advances, as being characterized by an increasing rapidity that will, through the development of informational technologies, proceed towards a succession of pure presents and simultaneous transmissions of information. In effect, Virilio warns of a veritable "digital amnesia," as the new media are seen as incapable of preserving memory due to the medium-specific tendency to store information in modular units, making all information processed functionally equivalent, with each bit of data able (theoretically) to be accessed as fast as any other. He sees this tendency beginning before the predominance of interactive and other computer-based media, writing, "While the illustrated history book evokes the mental imagery of real or emblematic memories, the television monitor collapses memory's close-ups and cancels the coherence of our fleeting impressions."6 Similarly, Virilio sees this tendency as being exemplified in the institution of cinema. He writes,

Finally, with the cinematic accelerator, itself conceived as an active prosthesis, the measure of the world becomes that of the vector of movement, of the means of locomotion that de-synchronize time. When [Etienne-Jules] Marey reduces the movement of life to certain photogenic signs, he makes us penetrate into an unseen universe, where no form is given us since all forms fill a different time, stripped of mnemonic traces, already.7

Marey's experiments in chrono-photography at the end of the nineteenth century manifest an attempt to segment time into discrete units, much as the data of a computer program such as Immemory takes the underlying forms of a binary code. However, Marey's work importantly retains the indexical character of photography that, with its accompanying analogous relation to reality, is altered with the digital turn. Undeniably, the digitization of the archive poses very real questions as to the permanence of storage and the ever-faster obsolescence of formats, but Virilio is quite eager to ignore the generative possibilities of digital media with regard to the archive and memory. To designate new media as anti-mnemonic is perhaps to proceed too hastily and to indulge in a nostalgic valorization, as well as to attribute an infallibility to analog storage that it never actually possessed. Instead of a facile demonization, in an art practice such as Marker's, the use of CD-ROM technology allows for an exploration of alternative techniques of transmission, effectively changing the way the user experiences the archive.

Virilio's critique of the simultaneity of technological time is a nostalgic lament to a prelapsarian experience of continuous time, unmarked by what he terms "picnolepsy," from the Greek picnos, to forget: the condition whereby the subject loses instants in time without being aware of the occurrence.8 If this asynchronous, technological time emerges always already discontinuous and stripped of mnemonic traces, Virilio does not venture to offer an account of the synchronous time he mourns and how it might proceed to archive time and memory. He, does, however, underline the importance of a witness in order for an event to be transformed into a memory; without a viewer to testify to the actuality of the event, it becomes a one ephemeral moment among many in the perpetual present of technological time.9

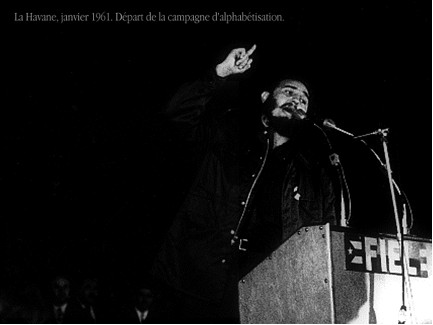

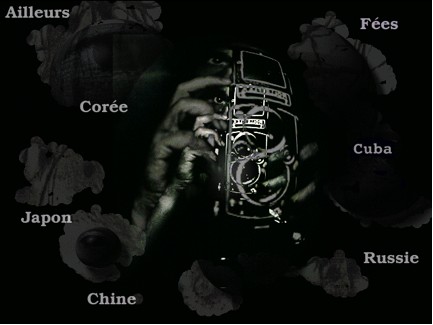

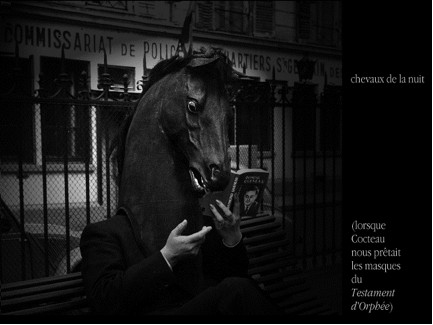

Is it possible to recuperate Virilio's necessity of a witnessing party to the possibility of a digital archive? Virilio tends towards the predictive elaboration of a dystopian future in which signals would be relayed automatically at a speed asymptotically approaching simultaneity, without the interval of action-reaction that characterizes human communication and older media. However, Immemory functions as a form of resistance in practice to such a mode of thinking that is often hyperbolic and overly rhetorical, affirming the possibilities of digital media to function as an archive of memory. If Virilio's witness may be understood as he or she who is present to the actuality of the event, lacking mediation through a technology such as the television or computer screen, Marker's work complicates this paradigm. Immemory partakes in a double gesture with regard to who exactly constitutes the witness to the event; in effect, this witness at once becomes both the creator (Marker) and the user of the interactive work. Marker uses the interface of the CD-ROM to organize archival documents from various older media- including painting, photography, cinema, and writing-all culled from his personal experiences. Older cultural interfaces are here transposed and assembled to be viewed through the interactivity of the CD-ROM. Those acquainted with Marker's work will recognize his favorite animals, the owl and the cat, photos of faces familiar from his previous projects, as well as his cherished filmmakers (Hitchcock, Tarkovsky, Kurosawa). Immemory does not attempt to probe a collective memory, but rather the intensely personal documents collected by Marker throughout his life and travels. And unlike Virilio's technological pessimism, Marker sees mediated inscription as perhaps the only way one can remember. The narrator in Sans Soleil reads from a letter sent to her by a filmmaker travelling the world: "I wonder how people remember things who don't film, don't photograph, don't tape. How has mankind managed to remember? I know: it wrote the Bible."10 Marker stands witness before the event but sees its inscription in media as necessary for the possibility of remembrance; the pure memory is always already externalized in its inscription, which is necessary if the moment is to be constituted as memory at all. Unlike Virilio, however, he does not see film, photography, and new media as radically opposed to the writing of books but rather as another kind of memory-écriture, providing different but not inferior possibilities of archivization. Marker, however, by no means unquestionably champions the role technology has to play in cultural memory. Indeed, much of his work is infused with a sad skepticism concerning the perfectibility of memory, often highlighting the ways in which media transform experience. But unlike Virilio, Marker never resorts to an idealization of mnemonic processes attributed to a society anteceding our own. Instead, he chooses to probe the complexities of the relations that exist between technology and memory, always interrogating the ways the different media work to help us constitute an archive and help us remember.

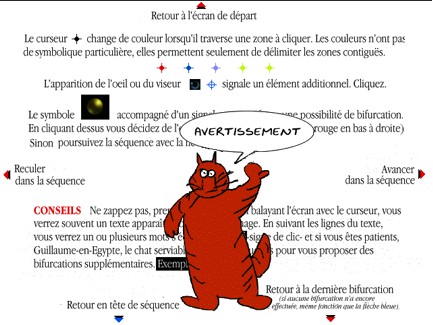

The physical, analog documents of Marker's memory are organized and encoded on CD-ROM as a means of transmission. The instructions to the CD-ROM advise, "Take your time! Don't zap!", instructing the user of Immemory to wander through the geography of Marker's own memory, free to explore bifurcating paths and make his or her own associations. The movements of the mouse cursor become very important, as certain options will only appear if the viewer places the cursor over a particular place that can only be found through experiment and exploration. Sometimes movement of the mouse will trigger a particular scroll of text to appear; if the user moves the mouse too quickly following this, the text will disappear, as well as any potential paths further into the work. Occasionally, Guillaume, a red animated cat, will pop up suddenly to ask, "Want to know more?", offering the user yet another possible bifurcation in his or her trajectory. Through these bifurcations, the user may end up in an entirely different zone than the one in which he or she started: from memory, to cinema, to war, lost in the many layers of the work.

Marker presents the user with an archive of his personal memories with the hope that "there might be enough familiar codes...that the reader-visitor could imperceptibly come to replace my images with his, my memories with his, and that my immemory should serve as a springboard for his own pilgrimage into Time Regained."11 This movement constitutes the essential project of Marker's work: the user becomes witness, not to the event as such, but rather to the event of the archive which functions in itself as a form of technological madeleine, an opening onto the user's own involuntary memory, before which he or she has born witness unmediated by technology. In this way, the digital archive challenges Virilio's quick condemnation of the mass media as destructor of the auratic experience surrounding a witnessing of the event. Here, the possibilities of interactive media are utilized to intensify experiences of memory and to organize the archive in a non-linear way that perhaps more closely approximates how the individual experiences memory.

This movement—from Marker's personal memory, to the creation of the archive of Immemory, to the provocation of associations in the mind of the user—also raises a pertinent question regarding the institutive function of the archive and the exteriorization of memory into the archive. Far from suggesting a conception of memory characterized by a pure interiority, Marker questions the ability to remember without an exteriorizing inscription in technological media, forcing one to consider: does an internal, pure memory precede the moment of archivization, or is the existence of the archive the precondition for any attempt at remembrance? Can there be memory without its exteriorization in the form of archival inscription? In Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, Jacques Derrida attempts to answer precisely such questions. Derrida evokes the Platonic distinction between hypomnesis on the one hand, and mnene on the other. This distinction sees mneme or pure internal memory, as never being present in itself, but instead always already supplemented by the archives, notes, documents-in general, memorials-that are constituted by hypomnesis. Whereas Plato dreamed of a pure memory not contaminated by the exteriority of the writing of hypomnesis,12 Derrida sees such a thing as impossible and therefore emphasizes the inevitable exteriorization of memory and, as such, its transformation into the archive. He writes,

The archive... is not only the place for stocking and conserving an archivable content of the past which would exist in any case, such as, without the archive, one still believes it was or will have been. No, the technical structure of the archiving archive also determines the structure of the archivable content even in its very coming into existence and in its relationship to the future. The archivization produces as much as it records the event.13

Harkening back to Nietzsche's aphorism that "Our writing tools are also working even on our thoughts,"14 Derrida underlines how the structure of the archive determines precisely what may be archived within it. Virilio's nostalgia for an actual witnessing of the event here becomes further problematized as it becomes necessary to recognize that memory is always already exteriorized, always archived in one form or another. Marker's assertion that it is impossible to remember without filming fits precisely this line of reasoning, as he embraces the capabilities of various media to constitute an archive that would not merely serve as a site of personal remembrance, but which would also spur new and different memories in those that encounter it. Marker's dream that "every memory would create its own caption," is in these terms is already a reality; each memory exists in a relationship of supplementarity to its archival medium, be it speech, writing, photography, cinema, digital media, or something else. Memory does not precede the archive, but the inverse is similarly untrue. In this context, Comay's opening comments become further elucidated as the ways in which the archive confounds attempts at linear organization and the positing of stable origins become palpable. The relation of supplementarity that exists between memory and the archive (or, if one prefers, between mneme and hypomnesis) may only be sufficiently thematized in a format that recognizes the impossibility of a linear sequencing of archival events and, as such, a linear sequencing within the archive itself.

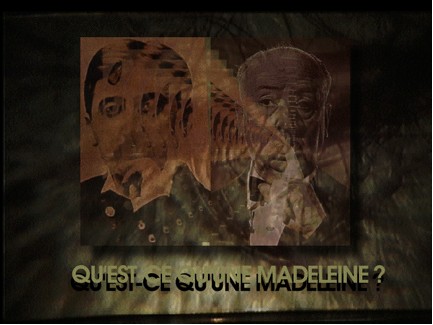

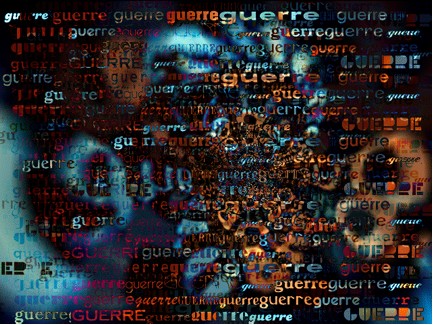

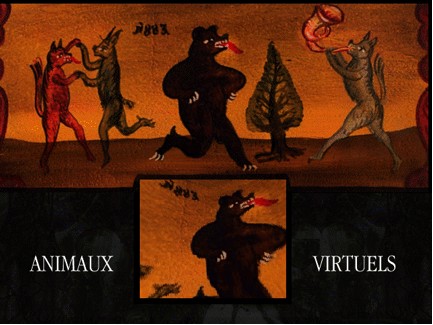

Immemory is divided into seven zones: memory, cinema, photography, poetry, museum, x-plugs, travel, and war. The user is free to navigate through these zones, which will sometimes interpenetrate through transversal associations. An index of names and topics (although not entirely complete) is provided so that it is possible for the viewer to easily find again a part of the work he or she particularly enjoyed, or even just to see how many corners of the CD-ROM have not yet been visited. The memory zone presents the user with the question, "What is a Madeleine?" and gives the option of following one of two paths: Proust or Hitchcock. Each leads in a different direction, with the Hitchcock path giving a meditation on Vertigo and its Madeleine, a character named as such played by Kim Novak.

Of the impossible wish of Jimmy Stewart's character, Scotty, Marker writes, "He simply wanted to conquer time. Madness, perhaps, but a madness which speaks to us. No other film has ever shown the point at which the mechanism of memory, if one lets it, may serve a completely other purpose than to remember: to reinvent life, and finally, to conquer death." Herein lies the function of the archive itself: André Bazin's assertion that the ontology of the photography image is bound up with "embalming the dead"15 is true not just of the photochemical print but of the movement of the archive in general. If the user glides the cursor over the texts that comprise this section of the work, certain words will become highlighted, offering a bifurcation the user may choose to follow if he or she wishes. With regard to Vertigo, these options often involve providing further information on an aspect or location of the film that has been mentioned, offering photos or supplementary details. Here again, Marker's insistence on technological forms as a conduit to memory is emphasized as the cinema reappears throughout various zones of the work as the dominant cultural form of the twentieth century, a personal obsession for Marker, and above all, a way of remembering.

Lev Manovich sees the future of cinema-what he terms broadband cinema or macrocinema-as characterized by an increasing spatialization of narrative that was suppressed by twentieth century cinema. He writes, "The logic of replacement, characteristic of cinema, gives way to the logic of addition and coexistence. Time becomes spatialized, distributed over the surface of the screen...In contrast to the cinema's screen, which primarily functions as a record of perception, here the computer screen functions as a record of memory."16 Marker works very much within such a paradigm, partaking in what one might term a "cinematic imaginary" despite his embrace of new media with Immemory.17 The work possesses no temporality of its own, but is determined solely by the ambulatory movements of the user through it. Instead, there is a building of layers that interpenetrate one another, with a given part of the work sometimes connecting to one section, sometimes to another. The content of the work interrogates processes of remembrance and archivization, but its form also manifests these ideas in its organization. This is not new to Marker's oeuvre; even in a 1958 article on Lettre de Sibérie, André Bazin writes, "Chris Marker brings an absolutely new notion of editing in his films, which I will call horizontal...Here, the image does not refer to the one that preceded it or to the one that follows it, but laterally in a way to what is said about it."18 The image does not signify in relation to a sequential, temporalized ordering, but rather through an associative spatialization. While a film such as Sans Soleil is often described as being organized in these terms, there is nevertheless the material constraint of the film medium, feeding singular frames through a projector at twenty-four frames per second. Temporality and sequentiality are inevitable, despite the employment of what Bazin terms "horizontal montage."19 With his use of CD-ROM, Marker is afforded the opportunity to better realize a project that has informed his entire oeuvre. Immemory generates meaning through transversal linkages: memories of childhood are elucidated next to photographs of world travel, quotations from literature, totem animals, and so on. Marker is able to break with montage as conceived of as the connection of one shot to the next as layers upon layers of meaning are superimposed upon one another, not only within the user's mind, but also literally on the screen as several images appear over top of one another on the computer screen. As Laurent Roth writes, "Here is where Chris Marker's master figure takes the stage: rapprochement, the art of bringing together the distant, which in his work is a veritable tic of imagination and thought."20

As a compensation for a loss of access to the auratic archival document, the user of Immemory is allowed a much greater interactivity with the work. In theories of the archive, much emphasis is put on the processes of archival assemblage, or what is essentially the writing of the archive. However, Marker's work accords a great deal of importance to the read function and, to invoke Roland Barthes' distinction, conceptualizes reading as a writerly practice in itself. Barthes makes a division between readerly and writerly texts; readerly texts display writing as an unforeclosed process and leave little to the reader while writerly texts possess a celebratory pluralism wherein "the reader [is] no longer a consumer, but a producer of the text."21 Immemory signifies in different ways for each user, as he or she chooses different paths and points of entry and makes different associations with his or her own memories. However, it is important to consider that the data encoded on a CD-ROM is of a finite nature; certainly, in this sense, Immemory cannot be considered to be interactive in the fullest sense of the word. The viewer does go over the same blocks of data with each subsequent viewing. Immemory exists as a closed system; as such, any conception of interactivity that may be discussed in relation to it is limited. The user is able to interact with the work, but the work will not change as a result of the interaction. While it is possible to conceive of a work that would radicalize the propositions regarding the digital archive that have been put forth in this paper, Immemory is not it. Such a work would involve an open system, able to be manipulated and changed by the user and which would itself change in response to these movements. However, Immemory may be understood as a writerly text in relation to the analog archive as it does allow for an increased interactivity that hinges on the trajectory of the viewer as he or she moves throughout the work. Unlike installation art, which presumes a physical trajectory through extensive space, Immemory engages in an intensive mapping that forces the user into the creative role of determining his or her own trajectory through the work, his or her own mapping of memory, and organization of the archive. Marker creates new topologies of memory in the work; in fact, in the introduction to the CD-ROM he speaks of memory in terms of "zones," "continents," and "islands," creating a forceful analogy between physical landscape and the psycho-geography of his memory.

Throughout Immemory it is possible to locate various loci of porosity and interpenetration. The seven zones that provisionally organize the work are shown to have shifting structures and rhizomatic associations; Marker's personal archive spurs involuntary memories in the mind of the user; the processes of reading and writing are interrogated as reading the work becomes an act of creation while its writing is emphasized as the product of a lifetime of browsing and collecting photographs, texts, films, and other documents. As Lev Manovich has noted, the interface of the computer screen has become "a battlefield for a number of incompatible definitions-depth and surface, opaqueness and transparency, image as illusionary space, and image as instrument for action."22 Immemory certainly plays with many of these interface-specific contradictions, but adds one further that is crucial to any consideration of the archive and memory in terms of their relation to new media art: the struggle between new media technologies' dematerialization of information and, as such, its fundamental incapacity to function as an archive, and the conception of the human-computer interface as a porous surface that allows for an engagement with memory hitherto impossible with the older media. The interface functions as a memory-conduit by allowing the viewer to actualize particular moments of the past, which is always virtual. As Henri Bergson writes,

For, that a recollection should reappear in consciousness, it is necessary that it should descend from the heights of pure memory down to the precise point where action is taking place. In other words, it is from the present that the appeal to which memory responds comes, and it is from the sensori-motor elements of present action that a memory borrows the warmth which gives it life.23

In Immemory, it is the human-computer interface that constitutes this moment of actualization of the pure past. This introduces an element of action into Proust's more passive conception of involuntary memory, as it is precisely the trajectory decided upon by the viewer, possible only through interactive technology, that memory becomes actualized. Instead of passively awaiting a sensation that would trigger a flood of pastness, here the user of the CD-ROM can navigate through different sections of the work according to his or her own preference.

This temporality sharply contrasts with the perpetual present that Virilio sees as characterizing the real-time of technological acceleration. In Immemory, one finds a non-sequential time that resists an extensive spatialization but instead forms intensive topographies always open to fluidity and change. Virilio may understand the "dromological" pollution of contemporary culture as replacing organic memory with the dematerialized residue of technological inscription, but such a view stems from a foundational idealization of memory and an inability to recognize the supplementary relationship that necessarily exists between memory and the archive. Such a misrecognition provides an easy justification for a wholesale condemnation of the digital with regard to its effect on mnemonic processes, much in the same way that early critics of photography and cinema lambasted these then-new media. There is a certain anxiety that accompanies all technological change and, without question, with good reason. However, if one looks historically at the emergence of film and photography, it is palpable that many of the anxieties expressed at the end of the nineteenth century now seem unfounded.24 While digital media certainly pose very real challenges to the analogical archive, it is important to remember how the socio-cultural conception of a given technology will change over time, especially when it is supplanted by a newer, more anxiety-inducing technology. With works such as Immemory, it becomes possible to see the temporality of the digital as not restricted to Virilio's inescapable, ever-accelerating time of technological advancement and instead see the computer interface as an agent in the actualization of the past for the user.

Bergson's conception of memory recasts the relation between past and present, provides a way to see Immemory's project of intensive cartography as possessing a very clear relation to pastness while still depending crucially on a present moment of actualization. The time of the archive has always been thought of in terms of a thanatological operation as documents are preserved in the archive as a way to surmount time, much as Marker identified Scotty's impulse in Vertigo as a way to reinvent life in order to conquer death. In this sense, the archival object becomes so only at a price: the embalming action of preservation consigns the document to a mortified, inert status. In Archive Fever, Derrida intimately links the archive to Freud's conception of the death drive; the preservatory impulse that characterizes the moment of archivization is doubled by an accompanying impulse towards destruction and a recognition of loss.25 While certainly what Derrida terms the "archiviolithic," destructive component of the archive may never be overcome or obliterated, the relative instability of the digital archive and its capacity for user interaction and manipulation of archival materials make it less aptly characterized as a repository of "dead" documents. The writerly practice of reading an archive of this kind introduces a notion of process into the user's experience of archival documents. Throughout Immemory, associations between various segments proliferate as the user's trajectory changes directions, slows or quickens. The interactive possibilities of the human-computer interface allow it to function as a membrane that will actualize certain moments of the past while leaving others as virtualities. This intensive movement of mapping the archive anew with every viewing is not merely a change in medium from analog to digital with minimal consequences. Rather, the entire functioning and structuring of the archive comes into question as sequentiality and fixed narratives are no longer possible. Rebecca Comay has noted how the archive confounds the time of history. Teleological views of the historical past have been subject to numerous astute attacks in contemporary cultural theory and, following such critiques, it is fitting that any theory of the archive would be marked by such vicissitudes. If the archive has always encountered difficulties in its attempts to replicate the time of memory in its organization, perhaps now finally with the advent of digital and interactive technologies, it may begin to take shapes that are much more fitting to its theoretical exigencies. Chris Marker's Immemory demonstrates the ways in which an artist who has grappled with these problems through a career spanning over fifty years has been able to best realize his practice through the employment of CD-ROM technology, which was already well on its way to obsolescence by the time Immemory was released. This rapid pace of changing formats comprises a great part of the anxiety surrounding new media storage, but does not exhaust it. Equally pressing is the loss that accompanies digitalization, as objects lose their independent material supports and are leveled to the indiscrimination of binary code. Walter Benjamin may have decried the decay of aura in the 1930s, but the tangible object still retains a tremendous allure for us all. Nevertheless, instead of hyperbolically proclaiming the amnesia-inducing nature of all digital technologies, perhaps it is more fruitful to experiment with these technologies to determine the ways in which they can provide new possibilities and capabilities unavailable before their inception. Immemory is one such experiment that leaves the question open for subsequent interrogations into the matters of media, memory, and archive.

About the Author

Erika Balsom is a doctoral student in the Department of Modern Culture and Media at Brown University. Her research focuses primarily on temporality in experimental and art cinema. email: erika_balsom@brown.edu

Notes

1 Rebecca Comay, "introduction," Lost in the Archives, ed . R. Comay (Toronto: Alphabet City Media Inc., 2002), p. 14.

2 "Finished, it's nearly finished, it must be nearly finished. [Pause.] Grain upon grain, one by one, and one day suddenly, there;s a heap, a little hap, the impossible heap..." Samuel Beckett, Endgame (New York: Faber and Faber, 1974), p. 1.

3 Hal Foster, "The Archive Without Museums," October, vol. 77 (Summer, 1996), p. 109.

4 Marcel Proust, Swann's Way trans. C.K. Scott Moncrieff and T. Kilmartin (New York: The Modern Library, 2003) pp. 63-64.

5 See, for example: Michael Wood, "Immemory Lane," Artforum (February 2003), available online: http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0268/is_6_41/ai_98123122; Uriel Orlow, "Chris Marker: The Archival Power of the Image," Lost in the Archives, ed. R. Comay (Toronto: Alphabet City Media Inc., 2002) pp. 436-453. Interestingly, those articles that do not concentrate on the specificity of the interface often menion in passing the virtual obsolescence of the CD-ROM format or the "tackiness" of Marker's work. On this issue, see: Guillaume Ollendorff, "Sorting it Out: Chris Marker's Immemory, Trans. A. Martin, Screening the Past issue 9 (2000), available online: http://www.latrobe.edu.au/www/screeningthepast/shorts/reviews/rev0300/ gobr9a.htm; Kent Jones, "Time Immemorial: Chris Marker's Maiden Voyage into the Uncharted Waters of CD=ROM," Film Comment (July/August 2003), available online: http://www.filmlinc.com/fcm/7-8-2003/immemory.htm. A notable exception to both of these tendencies is Catherine Lupton, "Chrismarker: In Memory of New Technology," available online: http://www.silcom.com/~dlp/cm/cm_memtech.htm

6 Paul Virilio, A Landscape of Events, trans. J. Rose (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000).

7 Paul Virilio, The Aesthetics of Disappearance, trans. P. Beitchmann (New York: Semiotext(e), 1991).

8 Ibid., pp. 9-10.

9 Virilio, 2000, p. 15.

10 The entire text of Sans Soleil may be found online: http://www.geocities.com/wolfgang_ball.

11 Chris Marker, Immemory (Cambridge: Exact Change, 2002).

12 In the dialogue of Phaedrus, the Egyptian god, Theuth, inventor of writing, brings his invention before the king, only to receive the following reply: "The specific which you have discovered is an aid not to memore (mneme, but to reminiscence (hypomnesis), and you give your disciples not truth, but only the semblance of truth; they will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing; they will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing; they will be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without the reality." In this sense, Virilio's conception of memory as depending on a witnessing of the event is quite Platonic. Plato, Phaedrus trans. B. Jowett, available online: http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/jod/texts/phaedrus.html.

13 Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. E. Prenowitz (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995).

14 From a letter towards the end of February 1882, in Frederic Nietzsche, Briefwechsel, Kritische Gesamtausgabe, Abt.3, Bd.1, Briefe von Nietzsche, Januar 1880 - Dezember 1884, ed. G. Colli and M. Montinari (Berlin: Gruyter, 1974) p. 172. Quoted in: Frederich Kittler, Gramophone, Film, Typewriter trans. G. Wintrhop-Young and M. Wutz (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999), p. 200.

15 André Bazin, "The Ontology of the Photographic Image," What Is Cinema? Volume I, trans. H. Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), p. 9.

16 Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2001).

17 Indeed, Immemory was included in an exhibition curated by Jeffery Shaw and Peter Weibel at the Centre for Art and Media, Karlsruhe, entitled "Future Cinema: The Cinematic IMaginary After Film,: 16 November 2002 - 30 March 2003.

18 André Bazin, "Bazin on Marker: Letter from Siberia," Film Comment (July/August 2003), p. 44.

19 Bazin's designation of this technique as "horizontal montage" stands in opposition to Sergei Eisenstein's conception of "vertical montage." See Sergei Eisenstein, "Vertical Montage,"Selected Works, Volume II: Towards a Theory of Montage, ed. M. Glenny and R. Taylor, trans. M. Glenny (London: BFI Publishing, 1991), pp. 327-399.

20 Laurent Roth, "A Yakut Afflicted with Strabismus," Qu'est-ce qu'une madeleine?: A propos du CD-ROM Immemory de Chris Marker (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1997), p. 52.

21 Roland Barthes, S/Z, trans. R. Miller (London: Jonathan Cape, 1974), p. 4.

22 Manovich, p. 90.

23 Henri Bergson, "The Persistence of the Past," From Matter and Memory in Key Writings, trans. and ed. K.A. Pearson and J. Mullarkey (New York: Continuum, 2002), pp. 132-133.

24 See, for example: Charles Baudelaire's Salon of 1857: "In these sorry days, a new industry has arisen that has done not a little to strengthen the asinine belief...that art is and can be nothing ever than the accurate reflection of nature...A vengeful had has hearkened to the voice of this multitude. Daguerre is his messiah." Quoted in Walter Benjamin, "A Little History of Photography," Selected Writings, Volume 2, 1927-1934, eds. H. Eiland and M.W. Jennings, trans. E. Jepcott (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999), p. 527.

25 Derrida, p. 10.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. R. Howard (New York: Hill And Wang, 1981).

Barthes, Roland. S/Z, trans. R. Miller (London: Jonathan Cape, 1974).

Bazin, André. "Bazin on Marker: Letter from Siberia," Film Comment (July/August 2003), pp. 43-45.

Bazin, André. "The Ontology of the Photographic Image," What Is Cinema? Volume I, trans. H. Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), pp. 9-16.

Beckett, Samuel. Endgame (New York: Faber and Faber, 1974).

Benjamin, Walter. "A Little History of Photography," Selected Writings, Volume 2, 1927-1934, eds. H. Eiland and M.W. Jennings, trans. E. Jepcott (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999), pp. 509-530.

Bergson, Henri. Key Writings, trans. and ed. K.A. Pearson and J. Mullarkey (New York: Continuum, 2002).

Comay, Rebecca. "Introduction," Lost in the Archives, ed. R. Comay (Toronto: Alphabet City Media Inc., 2002), pp. 12-15.

Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. E. Prenowitz (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995).

Doane, Mary Ann. The Emergence of Cinematic Time: Modernity, Contingency, the Archive (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002).

Eisenstein, Sergei. Selected Works, Volume II: Towards a Theory of Montage, ed. M. Glenny and R. Taylor, trans. M. Glenny (London: BFI Publishing, 1991).

Foster, Hal. "The Archive Without Museums," October, vol. 77 (Summer, 1996), pp. 97-119.

Jones, Kent. "Time Immemorial: Chris Marker's Maiden Voyage into the Uncharted Waters of CD-ROM," Film Comment (July/August 2003), available online: http://www.filmlinc.com/fcm/7-8-2003/immemory.htm.

Lupton, Catherine. "Chris Marker: In Memory of New Technology," available online: http://www.silcom.com/~dlp/cm/cm_memtech.htm.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2001).

Marker, Chris. Immemory (Cambridge: Exact Change, 2002).

Nietzsche, Frederic. Briefwechsel, Kritische Gesamtausgabe, Abt.3, Bd.1, Briefe von Nietzsche, Januar 1880 - Dezember 1884, ed. G. Colli and M. Montinari (Berlin: Gruyter, 1974).

Ollendorff, Guillaume. "Sorting it Out: Chris Marker's Immemory," trans. A. Martin, Screening the Past, issue 9 (2000), available online: http://www.latrobe.edu.au/www/screeningthepast/shorts/reviews/rev0300/ gobr9a.htm.

Orlow, Uriel. "Chris Marker: The Archival Power of the Image," Lost in the Archives, ed. R. Comay (Toronto: Alphabet City Media Inc., 2002), pp. 436-453.

Plato, Phaedrus, trans. B. Jowett, available online: http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/jod/texts/phaedrus.html.

Roth, Laurent. "A Yakut Afflicted with Strabismus," Qu'est-ce qu'une madeleine?: A propos du CD-ROM Immemory de Chris Marker (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1997).

Proust, Marcel. Swann's Way, trans. C.K. Scott Moncrieff and T. Kilmartin (New York: The Modern Library, 2003).

Virilio, Paul. The Aesthetics of Disappearance, trans. P. Beitchmann (New York: Semiotext(e), 1991).

Virilio, Paul. A Landscape of Events, trans. J. Rose (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000).

Wood, Michael. "Immemory Lane," Artforum (February 2003), available online: http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0268/is_6_41/ai_98123122.