Volume 1 Issue 1 (2008) DOI:10.1349/PS1.1938-6060.A.288

E-Poetry between Image and Performance:

A Cultural

Analysis1

Jan Baetens and Jan Van Looy

Introduction

From a cultural studies point of view, electronic or e-poetry is more than just an "object," a "genre," or a "medium;" it is a cultural practice or a "cultural form" in Raymond Williams' words (1975). In this paper, we will tackle some of the issues raised by such a perspective, which will be cultural rather than technological and our starting point will be the relative ignorance toward e-poetry as a form. Indeed, compared to similar evolutions in other media, e-poetry is not only in quantitative terms small business - there has been no global shift from poetry in print to e-poetry as there has been, for instance, in photography or music - it is also in critical terms marginal and hardly researched, let alone thoroughly analyzed and described. E-poetry exists, but it hardly receives any critical attention compared to traditional, printed poetry. We can only regret this lack of interest, but unless we would assume that the e-poetry form is a non-entity reducible to a mere story of high-tech gadgetry deprived of any literary value, we can give no single answer to those willing to valorize or reject the literary and cultural importance of e-poetry. Actually, one can give two rather different answers and as we will try to show, one has to make a choice between them. Hence the aim of this article is threefold: first, to define the two major positions one can adopt when studying e-poetry (Part I); second, to give a more detailed presentation of e-poetry as a cultural form (Part II); and third, to illustrate the way in which e-poetry and print culture interact (Part III).

Part I: Patrimonial vs. Cultural

The Patrimonial Stance

How can we study e-poetry? First of all, there is the position to which we will refer as "patrimonial" and which emphasizes what has been achieved in the past and regards what is produced today for tomorrow's use and pleasure. In other words, this stance actively historicizes and canonizes its object of study: two procedures which are inextricably linked, no canon without a clear conscience of a history and vice versa. Canon and literary history exist. There are various types of e-poetry that have succeeded one another in time, and we know, in an almost literal sense, the places to be, i.e. the websites, galleries, and museums to be attended and visited. Electronic poetry started with a phase of generative algorithms. Computers, then, were not used to process texts, but rather to generate them by manipulating rules and variables. This was followed first by a reinvention of visual poetry when computers came equipped with graphical user interfaces, then by a period of hypertextual (i.e., non-linear and interactive) writing. Of course we should keep in mind that this type of three-stage depiction is a serious simplification (see Van Looy and Baetens 2003 for a more extensive discussion). The strange thing here is that e-poetry, which occurs in principle "everywhere," i.e. in all three stages, and which is one of the most globalized and delocalized literary forms imaginable, has produced so rapidly a rather closed canon, whose solidity and stability is ensured by a relatively small number of gatekeepers: academic programs such as the Electronic Poetry Center, first at Buffalo, now also at Penn; academic journals such as Leonardo, PMC/Postmodern Culture and Electronic Book Review; museum gatekeepers such as the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis or the ZKM/Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe; festivals such as Ars Electronica and DEAF in Europe; and to a lesser extent, for its scope is slightly different, a portal site such as UbuWeb. This paradox becomes ever more apparent, when one realizes that in the age of globalization, it seems that the mechanisms of power, i.e. of selection, promotion, and exclusion, are strengthened rather than weakened:

The rise of international biennales from Seoul to Istanbul to Johannesburg, and the concurrent explosion of jet-setting independent curators, seemed at first to indicate that true globalism and multicultural diversity was at hand for the art world. But look at the catalogues for these megashows and you see that a master list is already coalescing. Independent curators trumpet their structural similarities to the peripatetic transnational business class: they eschew their desk-bound institutional colleagues, boasting that they curate from plane seats, and keep in contact via cell phones, hotel fax machines, alphanumeric skypages and, of course, email. (Lunenfeld 2005: 54)

But how should we regard e-poetry? How can we delineate it as a form? This question may come as a surprise, since it is widely accepted that e-poetry is not, or at least is not supposed to be, "digitized poetry," i.e., printed or handwritten poetry transferred to a digital environment, but poetry written specifically to be read on a screen. Yet, in practice, things are not so clear-cut. Many e-poems are most definitely first written on paper and only then translated to the new medium. Furthermore, our thinking of e-poetry falls unavoidably prey to what Marshall McLuhan referred to as looking at the present through a "rear-view mirror," i.e., our tendency to interpret the new in light of the old, "marching backwards into the future." This phenomenon is well-documented and studied by many important media historians and theorists, from McLuhan to Winston, from Bolter and Grusin to Gaudreault and Marion. It is therefore imperative to try to escape from this retrospective look on e-poetry and to provide a more "progressive" interpretation of what it is and what it is not. In this respect, we can produce a list of regularly mentioned features:

- e-poetry is interactive (and the reader becomes a writer or "wreader")

- it is a form of multimedia writing (good e-poetry is expected to be more than something to read; one is supposed to be able to "experience" it)

- e-poetry is mobile, dynamic, multiformal (in extreme cases it is even evanescent and momentary to such an extent that rereading a poem is literally impossible).

This type of definition does not bring us much closer to our goal, however. Older forms of poetry have also been interactive and non-linear. Think for instance of the ancient tradition of combinatory poetry, which can be said to have anticipated the logic of the database and of the 20th century tradition of collage and mosaic poetry. Other forms have been primarily visual, like some of the most radical experiments of e-poetry today, see for example Rasula and McCaffery (1998). Even the storage and evanescence problem is not as new as it seems since it can also be applied to the oral tradition.

More elaborate definitions have been proposed, presenting a more integrated view on the aforementioned characteristics. These have also tried to include questions of quality and merit, which is a controversial issue. Some theorists insist, for instance, on the fact that it is not enough to have new types of signs (mobile, strongly visualized, interactive signs) and new types of host media (a computer screen, a projection screen, a virtual reality environment). Instead, these technical innovations need to be accompanied by new types of content, preferably linked to the specific features of the signs and the medium in question (Hayles 2002).

This "integrated" approach helps to protect us from the rear-view mirror effect when dealing with e-poetry. It is a tool which can be used to distinguish between true and false e-poetry and it prevents us from embracing the idea uncritically that e-poetry is good just because it is new and modern. Hence, it can be said that this integrated view offers a useful set of guidelines for the patrimonial collecting and assessment of e-poetry.

The Cultural Stance

Despite the relative prominence of the "patrimonial" position, a drastic shift to an even more inclusive position may be required. What matters is not just that we demonstrate the merits of the field as it is being looked upon, but that we suggest other questions which should have priority. In other words, it does not suffice to demonstrate that e-poetry is more interesting than is generally believed; what is necessary is an approach that shows that e-poetry is different than expected. Essentially, what we require is a shift from an ontological to a more anthropological type of approach. Instead of asking what new media writing or more specifically e-poetry is, we should look at how is it used, in which cultural practices it is embedded.

In a sense, this is the shift from digital to virtual, i.e. from the technological foundation to its cultural application and function. This leads us to a more cultural studies-oriented reading of what can no longer be tackled as a technical or formal question only. A shift to a cultural stance is not necessarily to be seen as a new paradigm. We prefer reusing here the more modest and probably more practical figure/ground metaphor revitalized by Peter Lunenfeld:

In the best of the figure/ground illustrations, there's a moment when your perception "pops" and what had been the ground flips instantaneously into the figure.... This phenomenon is distinct from the paradigm shift, which (think Einstein and relativity) is essentially a narrative about invention. The paradigm shift ruptures the knowledge universe, whereas the figure/ground shift is fundamentally a transposition - the recognition of things that were already in the culture, but not central to its perception of itself. (Lunenfeld 2005:152-154)

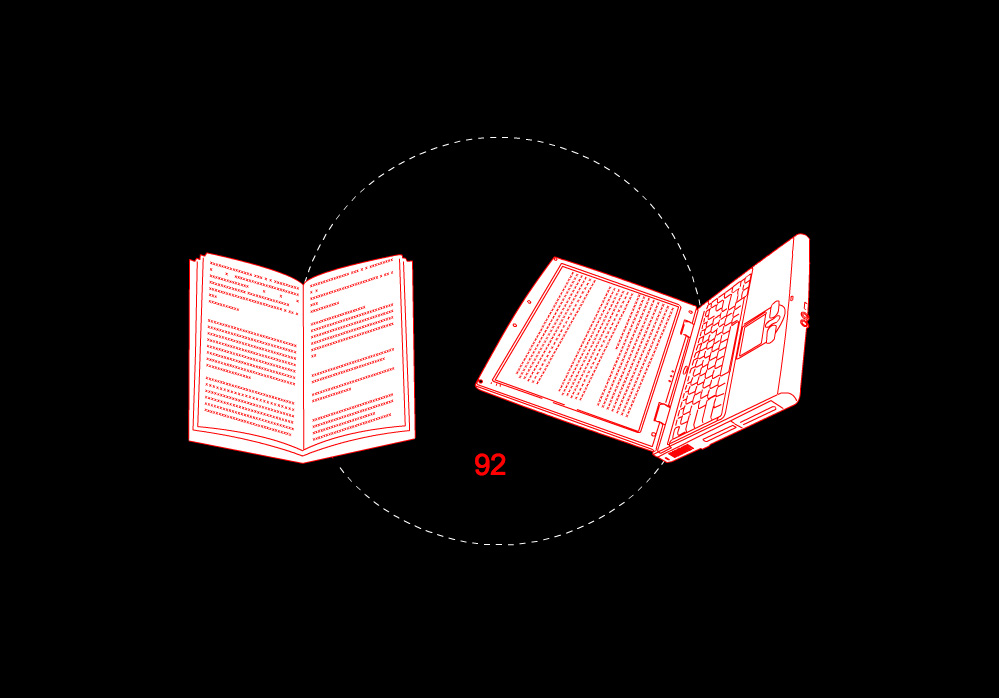

The first question that comes to mind when deploying this new framework is the following: is there an actual difference at the user level between print and on-screen poetry? As argued by W.J.T. Mitchell (Mitchell 2006), on whose ideas this part of our discussion will be based, it is difficult to accept that there is an ontological difference between a traditional (or analog) image on the one hand and a digital (or digitized) one on the other. It is indeed impossible to establish a clear boundary between analog and digital imaging because all images today have become digital, or at least digitizable. The conclusion drawn by Mitchell is not that digitization does not matter however. On the contrary, even when there is no ground for an ontological opposition between analog and digital imaging technologies, what changes radically is their social use. Digitization has not dramatically changed the form and content of the image (and if it did, it did so to a much lesser extent than we generally believe), but it has revolutionized the way in which we deal with images. Today, images circulate more easily and more rapidly than ever; they reach a wide audience in no more than an instant; and they can easily be transferred from one device to another. Hence, from this viewpoint, the difference is considerable: pre-digital and digital images may more or less look the same, but their uses diverge significantly, mainly because digital images are open to more individualized forms of transformation, circulation, and reuse, and are therefore more open to social negotiation. We have grown more suspicious of images and have become aware of the fact that the persuasive power of pictures, which of course has not disappeared, may need to be enhanced by other means. Velocity plays a key role here: the faster an image appears in the social domain, the more significant it seems.

A similar argument can be made for e-poetry. What is being produced, read, and commented upon under the label of e-poetry generally does not differ radically from what is called "avant-garde poetry." Many e-poetry websites hardly make any distinction between e-poetry and avant-garde, a blending which is, of course, symptomatic. At the same time, it is not very important to determine whether there does or does not exist any serious or structural divergence between poetry in print and e-poetry. Even if these differences seem to be more visible in the field of poetry than in the field of the image,2 this is not the question that matters. What needs to be examined is the way the domain of poetic writing has been affected or even revolutionized by the global transition towards cyberculture. Digitization is invading all types of poetry today, and this is of course a phenomenon that should be interrogated. The two examples close-read in Part III will demonstrate that e-poetry and poetry in print should not be looked at separately, as both types function within the larger network of contemporary poetry as a whole.

Part II: E-poetry as Cyberculture

The best way to study the impact of cyberculture would be to "transfer" the observations that have been made in the field of the image, where the mechanisms and impact of digitization have been studied more thoroughly than for writing, especially poetry. This would be too simple a solution, however, and at the same time would neglect the more idiosyncratic aspects of both the transition and the difference between both cultural forms. Some of the accompanying effects (some of the consequences?) of cyberculture's commitment to poetry may in fact be rather unexpected.

Sound and Sight Revisited

One of the more striking features of e-poetry is the fact that its link with visualization is less pronounced than expected. In the early 1990s, it was generally believed that digital writing would take advantage of the computer's increased ability to intertwine the verbal and the visual to produce a new species of poetry, first in a static and later in an animated form. With the widespread use of Flash, this eventually ceased to be wishful thinking, resulting in ever more complex medial forms, with sound added for instance. Yet visualization of e-poetry is not what is happening right now, and it is far from its most salient feature, which is rather its link with the oral tradition. If we were to give a survey description of the field, it would appear that e-poetry is often, albeit in sometimes paradoxical forms, related to slam poetry formats, VJ-culture, and with the once-again hot medium of radio, a popular venue for all kinds of experimentation. This link with oral forms goes much further than the inclusion of sound in websites; it reveals on the contrary a new, or rather renewed, interest for the oral as such (Bernstein 1998).

From a cultural viewpoint, there are several reasons for justifying a strategic alliance between e-poetry and sound, but the strong embedding of e-poetry in the historical avant-garde is by far the most salient one. A second explanation for the text-sound link is a mechanism of psychological compensation. It is often argued that cyberculture virtualizes the body, and that this virtualization engenders different types of fear that need to be averted by an opposing mechanism of foregrounding the body. And third, there is also the fact that digital artifacts, even when they are produced in order to be "read on the screen," are not always used as intended. One of the unexpected, and therefore all the more important challenges for digital art, is to just make it work. Reality has taught us to be careful. Most of the time, technology does not work, and its correct functioning requires a lot of time, people, energy and money. Hence the encounter of the creator and the user of such a work does not take place "on a screen or in cyberspace," but it is very much a physical event. This is what Peter Lunenfeld calls, analogous to the "do or die" procedure, the "demo or die" aesthetics of cyberculture (2000: 13-26). Digital writing obeys comparable inclinations: it tends to be staged, to be disclosed in the form of a performance, for instance when e-poetry or e-writing is displayed in blockbuster events such as the Biennale in Venice, the Documenta in Kassel, or, more specifically, for e-poetry in gatherings such as the already-mentioned Ars electronica or DEAF festivals, to name the most famous ones. Moreover, it does not suffice that when the evidence is delivered, at the correct time and in a specific place, that the writing "works." The success (or its failure) also has to be communicated outside the walls of the place where the performance takes place. Documentation can be produced in many ways: a performance can be converted into a book, it can be taped, and both these forms can be digitized and distributed as a DVD or through a website, for instance. Most of the time, this is the way we learn about these performances: through digital communication, whatever the initial form of the practice or the event may have been.

The idea of studying e-literature as performance is not new, as shown by the work by Rita Raley on hypertext (2001). Performance, in the case of Raley, is used in the same spirit as we do in this article, namely as an alternative to the essentializing and ontological analysis of the difference between literature in print and that delivered digitally. Our article shares Raley's conviction that such an essential opposition does not exist, and that the only way of mapping the differences is by studying the various effects induced by forms of reading and writing on the level of their respective performances. According to Raley, who partly relies on a system-theoretical framework, and who foregrounds notions such as "combinatorial writing," "linking," "self-reflexivity," and "anamorphosis," these effects are more "complex" in the case of e-literature. "The patterns and the system become not only complicated, but complex - that in which one not only gets lost, but also vertiginously loses stable and totalizing perception." (Raley 2001, section 30). In this article, however, the concept of performance is used in a broader sense, including not just the machine-mediated interactions of reading and writing, but also the larger cultural context of e-poetry in action.

Work, String, Network

E-poetry never walks alone in the cybercultural field of literature. It is accompanied by a set (or rather a "mode") of performances, and integrated in a circuit of distribution, both digital and non-digital. On this level, the very distinction between poetry and e-poetry is fading away despite the medium-specific features of each of these practices.

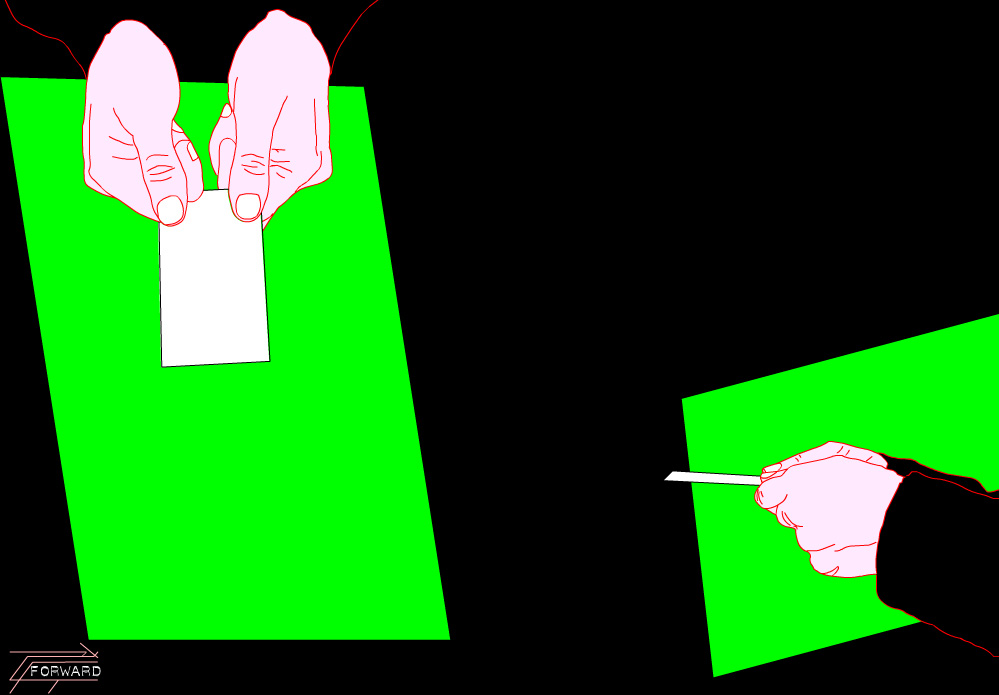

The distribution of writing is sequenced. Even when everything is available simultaneously, the concrete operations that take place do not all happen at the same time. Hence the importance of conceptualizing poetic works in terms of strings, i.e. of a succession of occurrences that can differ from a media-technical point of view. This shift from single work to string of occurrences can easily be confused with the shift to an increased multimedia character which most critics associate with digital writing, yet entails structures and mechanisms that are different.

In the first case, e-poetry as a token of multimedia and hybridization, the transition from text to multimedia - or, to put it more simply, from the linguistic token of the work to a combination of words and images - is a matter of choice between media and form. In the second case, the shift from work to string, the change deals with the transition from a "single-medium" text (be it a plain or a multimedia text) to "multiple media occurrences": the new format no longer implies a choice between this or that medium or form, or the substitution (read: remediation, in the Bolter & Grusin sense of the word) of this type of presentation by that one, but the insertion of the work in a set of occurrences that complete (and why not also compete with) each other.

In other words, in the first case, the main difference is paradigmatic. It is that between strictly verbal poetry on the one hand and multimedia works on the other, a contrast which tends to, at least partially, coincide with that between poetry in print and e-poetry. In the second case the major opposition is situated on a syntagmatic level: between works congealed in one (multi-) medium and works that are spread over a whole set of media occurrences. In the first case, poetry can of course also occur in various forms and media, but the relationship between these forms is not neutral: there is always one "basic" form from which others are derived. Take for instance "oral" poetry reproduced in print of which people will think as nothing more than a "pale copy" of the spoken "original." Or take public readings of poems that are actually made for close readers having the possibility of multiple rereadings; again one will think of these public readings as nothing more than a shadow of actual poem etc.3 In the second case, however, there is no longer a hierarchy between these various forms, although their distinction does not vanish completely. The network is not a set of "primary" and "secondary" forms, but as an entanglement and dissemination of related occurrences, each with their own specific features, each producing their own excess or surplus value. Today, a poet is supposed to do performances which are expected to be more than just the reading aloud of printed texts. Moreover, when documented or recorded, these performances will be used, transformed and continued in other media. Is this entirely new? Not really, since media culture (i.e. the state of culture in a society dominated by mass media) has consistently promoted, and even imposed, the multiplication through various media (see Kalifa 2001). What should be stressed in the present discussion is that the distinction between poetry in print and e-poetry is fading away, not in the sense that their distinctive features are being merged - we will see in the two examples below that quite the opposite is the case - but in the sense that both are now part of a larger cybercultural whole.

Until now, two metaphors have been mixed in the description of the new media environment of poetry: that of the network (a more spatial metaphor: the coexistence of various media forms of one work) and that of the sequence or string (a more temporal metaphor: the transformation of a work in always new forms). Is this coexistence pacific, or is one of the metaphors more appropriate or more accurate than the other? Actually, none of these questions is of paramount importance, for what happens in reality is that the permanent and complete availability of all possible forms is utopian: when reading, analyzing or writing poetry, we are always confronted with partial structures; the complete network or the full string is never disclosed. Hence the necessity to take fully into account the specific characteristics of each occurrence, as the examples will show.

Back to Print

One field phenomenon to which these reflections can be applied is the return of the print form in cyberpoetry. Until recently, most scholars and critics have been emphasizing the necessity to rethink the basic notions of text, author, reading, work, meaning, etc. in light of the global shift from traditional print culture to digital culture. "From page to screen," was the overall credo during a decade of efforts to tackle the issues of cyberculture in writing. Today, it has become possible to rephrase these observations the other way around from a less teleological perspective. Moreover, this new perspective is not, in the cultural stance we are defending, a retrograde or reactionary position, but a crude necessity if we wish to understand the present field of electronic poetry, i.e., not in dreams or theories but on the actual battlefield of creative writing.

Printed poetry has far from disappeared. On the contrary, whereas print poetry is "going digital," we also have digital poetry that is "going print." In discussions on writing and cyberculture, certain print works are often mentioned as forerunners of e-writing, the usual suspects being books such as Queneau's Cent mille milliards de poèmes, Pavic's The Khazar Dictionary and Cortazar's Hopscotch. What is less frequently considered, however, is the emergence of a type of writing that reworks and reformulates some of the lessons of e-writing in print form, often in a sophisticated and innovative way. The novels by Danielle Mémoire (2000), for instance, are a good example of such a adaptation of the database and the hypertext aesthetics, but there are many others. In this text, we will restrict ourselves to poetry however.

The spread of new media poetry represents a challenge to, but also an opportunity for, poetry in print. At first sight, we already have a concept at our disposal that helps us to theorize this phenomenon: repurposing. In Bolter and Grusin's remediation theory, which we will not discuss in great detail here, repurposing is defined as making a creative copy of the features of new media by older ones, which want to compete with the former by integrating some of their elements (Bolter and Grusin 1999). A good example of this phenomenon is the way the layout of newspapers has changed: a page of USA Today has come to resemble a multimedia website. Yet here again, one has to ask whether this explanation is not too mechanical, and for that reason too simplistic. In light of what has been discussed above we see two major problems. First, repurposing (and remediation in general) reflects a linear way of thinking, with a strong rhetoric of ahead and beyond, and does not acknowledge the fact that works tend to be part of networks with multiple media forms residing around the same work. In remediation/repurposing theory, works and media continue to be islands rather than strings or networks. Second, repurposing, if we wish to maintain the concept, does not actually take place the way it is supposed to. What we observe in practice, at least in the field of e-poetry, is that new forms of printed poetry that reformulate e-writing do not try to copy or to cannibalize its features. On the contrary, their use of book, typeface, page lay-out and so on, does not duplicate its style at all. From a cultural viewpoint, this is not so surprising: what we see here, are practices of re-specification.

Part III: Back and Forth Between Books and Bytes

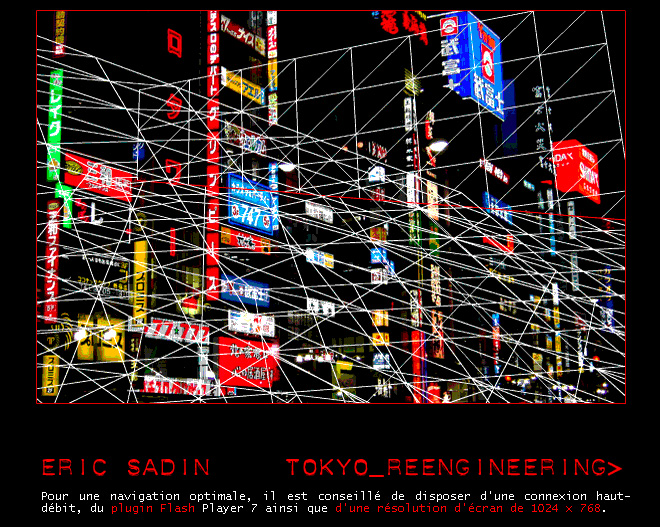

Eric Sadin: Tokyo

In the past five or six years, writer, multimedia artist, and cultural critic Eric Sadin has put forward a thoroughly artistic, and at the same time practical and theoretical reflection on the concept of representation, a framework of ideas dealing with new textual ways of representing the multimedia urban environment. In this sense, he could be seen as an successor to French "modernists" such as Michel Butor (see for example books such as Mobile, 1962) and Maurice Roche (Compact, 1966). Sadin's first landmark publication, 72 (read "sept au carré") is the transposition in bookform of what "happens" at a certain moment at the intersection of 7th avenue and 49th Street in New York. Using the number 7 as a constraint, it mixes seven types of stories and seven types of typographical styles in seven-times-seven well-distinguished sections (see also Baetens 2003). In doing so, the text becomes a literary "map" reflecting the post-modern metaphor of geography for writing processes as well as for website structures (see Ciccoricco 2004).

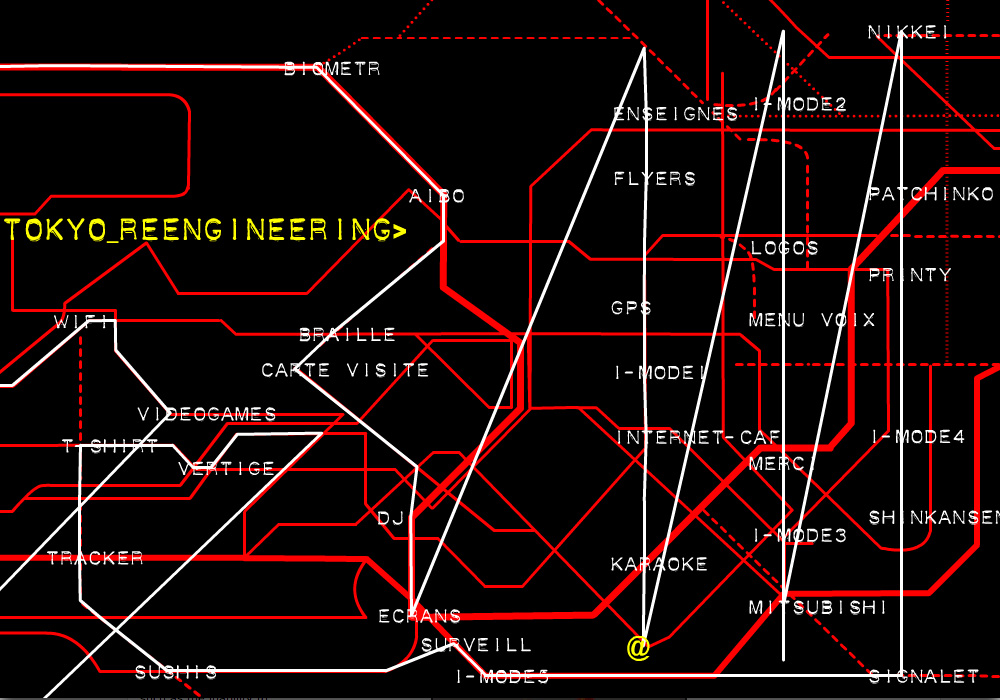

His more recent work, Tokyo (Sadin 2005), is part of the same global project, but it takes a form which reflects the issues of writing in the digital era in a way that is both more direct and more paradoxical. Tokyo is a textual reinterpretation of a web project launched under the name After Tokyo (see: www.aftertokyo.org), which presents itself as a kind of map one could find in a subway station. The general ambition of After Tokyo is to provide an overview of travelling and e-communication in contemporary Tokyo, from reading Manga in the high-speed train to sending email, from reading digital billboards to singing in a karaoke bar. It is not to suggest that the difference between travelling and communicating is blurring, but that each way of moving through signs obeys its own visual rhetoric. Each object has its own visual form, and given the post-modern setting, it should be acceptable to call these forms "ornaments." Strangely enough, the writing protocol makes this overwhelming web project clear and transparent, while allowing it to take advantage of the typographical and visual solutions offered by new writing technologies.

What is striking in Tokyo however, is the extreme minimalism of text and lay-out. The various objects (of communication and travel) are typographically represented in precisely the same way and there is an almost didactic use of the unity of the page: to turn the page (or the double page) means changing subject and linguistic style. Whereas After Tokyo employs a different rhetoric for every element, Tokyo's elements share the same rhetoric and the same space: that of the page or the double page, which is not the same as that of the screen. This minimalism is in complete opposition to the new doxa of postmodern typography, which promotes maximalism, i.e. systematic changes of forms and shapes not only between semantic units but within these units as well (see Peter Lunenfeld's collaboration with Mieke Gerritzen in User, 2005). We will not insist too much on this distinction as we know how unpredictable the relationship between minimalism and maximalism can be (Dawans 2004). It should be clear, however, that one of the great advantages of any minimalist approach is that it helps to focus as well as to avoid useless side-effects. This is of course true both for the maker and the public of the work, see Calvelo and Hamel (1986).

But let's go back to the book version of Tokyo itself so that we can describe a few more differences with After Tokyo. Contrary to the web project, there is no attempt, despite the deletion of the page numbers, to create a totally non narrative work. The overall structure is determined by what Bordwell and Thompson in film theoretical terms would call a "categorical formal system." (1997: 130-139). Soon, however, temporal and narrative effects start appearing, and their growing impact is part of the literary program of the book. The reader is invited to discover the narrative by linking non contiguous elements, for instance snapshots of the progress of the Football World Championship projected on big screens throughout the city. On a microscopic level, once the global perception of a basic narrative is established, the reader can develop an increased sensibility to the narrative virtualities of the very succession of words and sentences, a mechanism described by Jean Ricardou in his analysis (1967: 56-68) of the famous New Novel descriptive techniques of the 1950s and 1960s, where totally plotless descriptions eventually produced, by the very potentialities of the strings and sequences of words, a purely verbal narrative. This gradual shift toward narrative, in a globally non-narrative environment, is an important device in the "declaration of independence" of the book, which increasingly diverges from its digital starting point.

Another crucial difference between website and book is the absence of section titles in the latter. Unlike the website, where the "sections" of the map are clearly titled, the "chapters" (?) of the book are not summarized by shortcuts of this type. The lack of titles makes the reader more active, because he has to decide for himself which thread links the elements of a given page. This more active type of reading forces the reader to ask questions on two specific stylistic features of the book. First of all, there is the fact that Tokyo replaces the traditional distinction between "lexical" and "grammatical" words by a new distinction between words (either grammatical or lexical) and proper names. These behave almost like the zeroes and ones in a digital system. The reader scans the string of words until he encounters a proper name, after which he continues to the next one, and so forth. This foregrounding of proper names also gives a hint at the strange typographical "understatement" of Sadin's book: if the impact of Tokyo is so visually powerful, this is not due to any typographical experiment or adventure. Contrary to what we see in the works by Sadin's forerunners, Butor and Roche, this is the result of the cognitive impact of proper nouns, which today present themselves with a strong visual aura. A proper name such as Sony, for instance, is not just a name. It is a set of images, which the use of words instead of pictures could reproduce or suggest without a problem. This is a good example of the possible "maximalist" effect of a "minimalist" work. Moreover, the use of the word/proper noun opposition instead of the grammatical/lexical opposition is accompanied or reduplicated on the level of the sentence by a similar shift from words versus punctuation to words versus "icons" (for instance, arrows, emoticons, and so on). Here too, we observe a similar mechanism: the strong dichotomy of two categories of print forms transforms the reading process in a kind of binary scanning which heavily privileges the recurrent icons. Again, Sadin's minimalism produces a maximalist effect as each page or double page exploits only one class of icons, and this simplification enables the icons to be looked at and become loaded with meaning. Meaning is use is attention, to paraphrase Wittgenstein and to parody Stein. Tokyo's icons, whose function is primarily that of an alternative punctuation, increasingly draw attention and impose their own visual structure and logic upon the text as a whole.

Finally, the gradual disclosing of visuality in a text which itself seems to be deprived of any "oversized" grammatextuality, and which definitely does not have any illustrations, helps to reconsider the fundamental opposition between the narrative and the non-narrative in Tokyo. As argued above, the book unfolds a number of temporal and narrative structures that all underline its autonomy. It is largely thanks to this type of mechanism that Tokyo is more than a printed clone of After Tokyo. Nevertheless, the artistic reworking of words and sentences and the insistence on a digital reading logic of "marked" and "unmarked" elements, whose nature is more visual than verbal, forces the reader to rethink the status of the narrative. This status is ambiguous. On the one hand, the appearance of narrative continuity, however shattered it may be, contests the spatial logic of the map that is dominating After Tokyo. On the other, this global continuity is contested by the very literary elaboration of Tokyo itself, which induces, at another level of the reading spiral, various kinds of non-narrative effects. These tensions and contradictions are what make the double work After Tokyo/Tokyo such a stimulating experience.

Pierre Alferi: Intime

Our second example is different from the first. Contrary to Sadin, Alferi does not start with a digital work in order to infer a book from it. Instead he uses a small book, equally entitled Intime, as a "script" (to quote the publisher) for a short movie, which is integrated in a CD-ROM with performances of contemporary poetry. It is presented by the publisher of the CD-ROM as a "reading," similar to the "readings," i.e., live performances by the other seven poets gathered in the digital anthology. Apart from that, Intime also diverges from Tokyo by a certain degree of maximalism: texts and images are intertwined, as are other visual elements and sound, homogeneous and multiple screens, fixed and moving images, each time continuously presenting different relationships between the verbal and the visual. In this respect, Intime's style obviously goes back to today's aesthetics of the mosaic (Dällenbach 2002, Belloï and Delville, 2005). A final difference between Alferi and Sadin is the fact that Intime functions as part of a collective enterprise. It is the "chapter" of an anthology which is a small-scale model of the catalogue of a publisher, which in turn reflects the cultural policy of a certain type of institution.

There are also intriguing correspondences between Tokyo and Intime, however. These occur on the level of the author's work as Alferi, too, has been working a lot on the interplay between the verbal and the visual and has quite an interesting record in the field of e-poetry (cf. his work Cinépoèmes). Apart from that, they also occur on the stylistic level and that of the global mechanisms of e-writing between image and performance that are central to recent developments in the field.

First of all, we would like to stress that the digital version of Intime, as well as Sadin's work, tackles several myths that surround the idea of e-literature, for instance the interactivity myth or the myth of the reader as writer. What we observe here, is a straightforwardly presented work, that we read on a screen, nothing more and nothing less. Consequently, Intime devotes significant attention to the clear and transparent presentation of its material, mainly of the text borrowed from the original book version. This craving for clarity and transparency is visible throughout the entire work.

In the digital version, the many stories of the book, in which each poem is addressing a different person or a different role, are reduced to a single story. The addressees are deleted in a mechanism that reminds us of Sadin's cutting of the section titles, although the effect is not the same. Thus the whole story appears in a more homogeneous form, especially if one takes into account that the basic plot structure of the book has not been altered (it tells the story of a journey by train, with a departure, an arrival, a way back, and a return home). This simple narrative framework is crucial for a better reading of the images, which are often complex but never chaotic. We stay light-years away from the fashionable overkill of some postmodern video clips. Without the narrative, there would be a real risk of careless and untidy reading of the images.

Furthermore, the text from the book is only partially taken over in the CD-ROM. As in the case of the transition from After Tokyo to Tokyo, a careful selection has been made in order to avoid any verbal overload which is present in many examples of "early" e-writing, in which the number of elements to be read and the speed of doing so is so high that the screen-reader is rapidly confronted with his own biological limitations. Not all the lines of the rather short book of poems have been used, and the montage stresses the smooth and poised passages from one line to another. Alferi has made explicit efforts to achieve a maximal reading fluency, both on the level of technical readability and on the level of literary legibility. From a technical viewpoint, the CD-ROM version of Intime does not have any textual fragments that are difficult to read: the lines are placed against a background that is sufficiently contrasted with the shape of the characters. The words are not "manipulated" as opposed to the images, to which a complex, multiple split screen technique is applied. The amount of words is systematically low. The short lines appear one after the other, and the expected reading time is comfortable, neither too fast nor too slow. From a literary viewpoint, Intime pursues a classic form of lyrical poetry that does not destabilize the reader's expectations.

Despite differences in medium, style and technique, the digital Intime uses a significant number of mechanisms that are directly comparable with Sadin's Tokyo. This may seem bizarre as one would expect quite the opposite. It should come as such a surprise, however, because, as argued before, it is time to abandon the teleological one-way interpretation of the relationship between "print" and "screen" and to analyze the various forms of a work in their network(ed) environment, from which new and different questions emerge. In the works of the authors in question, these regard issues of medium-specificity and readability, of literary strategies, minimalism and maximalism. What is important to emphasize is the fact that both Sadin and Alferi have assimilated the notion of "evolving" works. A "text" which can be produced in whatever medium or combination of media is part of a "string" of versions that gradually composes an ever-shifting network of meaning. Each new configuration enriches and transforms the given relations, but it would be wrong to infer from such a policy that all works merge into a kind of global and globalized multimedia regime. Each new version, on the contrary, explores again and again the opportunities and the risks of specific environments.

Conclusion

The opposition between two ways of studying e-poetry and the approach of e-poetry as a cultural practice has helped us to achieve a double goal. On the one hand, it has enabled us to defend the specificity of e-poetry on non-essential or non-ontological grounds and to analyze it as a form of social performance. On the other, it has enhanced the multiple affinities that exist between the field of e-poetry in the narrow sense of the word and that of poetry in general. The two examples that we have close-read have illustrated each of these claims while permitting us to insist on the phenomenon of feedback to the poetic field. E-poetry is not a logical successor to print poetry, but a new form, and its very appearance changes the poetic field as a whole, including the subfield of print poetry that "comes after" the digital revolution.

About the Authors

Jan Baetens is professor of Cultural Studies at the University of Leuven (Belgium). As a poet, he has recently won the "prix triannuel de poésie de la communauté française de Belgique". email: jan.baetens@arts.kuleuven.be

Jan Van Looy holds a PhD on game studies from the University of Leuven and is currently working as a postdoc at Umeå University (Sweden), where he is doing research on digital culture. email: jvanlooy@gmail.com

Endnotes

1 A draft version of this text was presented at the "II Jornada de la literature comparada (Tecnologias de la creacion en la era digital)," University of Alicante, 24-27 October, 2005.

2 Although we do not think one should overemphasize the importance of features such as visuality, interactivity, and mobility in "liquid" or "soft" (see Manovich and Kratky 2005) poetry. There have been "wild" applications of technology in pre-digital poetry too (see North 2005: 74-82, for an "archaic" example of "pre-memex" poetry in combination with the futurist avant-garde ethics of mobility and speed).

3 This is a complex issue, however. Mallarmé was reputed for his reading aloud, and some (eye and ear) witnesses were convinced that his reading made his hermetic poetry very clear. Mallarm�� was probably one of the first to link the notion of poetry with the broader notions of theatre and performance.

Bibliography

Alferi, Pierre. Cinépoèmes (2004), available at http://www.inventaire-invention.com.

Alferi, Pierre. Intime (poésie) (2004), Paris: éd. Inventaire/Invention.

Alferi, Pierre. Intime (film, 15 min.), in Panoptic: Un panorama de la poésie contemporaine (CD-Rom), Paris: éd. Inventaire/Invention.

Baetens, Jan. "Eric Sadin en dialogue avec Jan Baetens au sujet de 7 au carré," in FPC/Formes poétiques contemporaines, No 1 (2003) 319-327.

Belloï, Livio and Delville, Michel. L'oeuvre en morceaux. Bruxelles: Les Impressions Nouvelles, 2005.

Bernstein, Charles, ed. Close Listening: Poetry and the Performed Word. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Bolter, Jay David & Grusin, Richard. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999.

Bolter, Jay David & Gromala, Diana. Windows and Mirrors: Interaction Design, Digital Art, and the Myth of Transparency. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003.

Bordwell, David & Thompson, Kristin. Film Art (5th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill, 1997.

Butor, Michel. Mobile. Paris: Gallimard, 1962.

Calvelo, José & Hamel, Patrice. "Géographismes," in Conséquences, No 9 (1986), 37-40.

Ciccoricco, Dave. "Network Vistas: Unfolding the Cognitive Map", in Image (&) Narrative, No 8 (2004), available at : http://www.imageandnarrative.be/issue08/daveciccoricco.htm

Dällenbach, Lucien. Mosaïques. Paris: éditions du Seuil, 2002.

Dawans, Stéphane, ed. Special issue on "Minimalismes" in Interval(le)s (Autumn, 2004), available at: http://www.cipa.ulg.ac.be/intervalles1/contents.htm.

Gaudreault, André & Marion, Philippe. "Un média naît toujours deux fois", in Sociétés et représentation ('La croisée des médias'), No 9 (2000) 21-36.

Hayles, N. Katherine. Writing Machines. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002.

Kalifa, Dominique. La culture de masse en France 1, 1860-1930. Paris: éd. Complexe, 2001.

Lunenfeld, Peter, Snap to Grid: A User's Guide to Digital Arts, Media, and Cultures. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000.

Lunenfeld, Peter. User: InfoTechnoDemo. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005.

Manovich, Lev & Ktayky, Andreas. Soft Cinema. Navigating the Database (CD-Rom). Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005.

McLuhan, Marshall. The Medium is the Message. Corte Madera, CA: Gingko Press, 2001; first edition: 1967.

Memoire, Danielle. Les personnages. Paris: P.O.L, 2000.

Mitchell, W.J.T. "Realism and the Digital Image", in Jan Baetens & Hilde Van Gelder (eds)., Critical Realism In Contemporary Art. Around Allan Sekula's Photography. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2006, pp. 12-27.

North, Michael. Camera Works. Photography and the Twentieth Century Word. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Nunberg, Geoffrey. The Future of the Book. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

Raley, Rita. "Reveal Codes: Hypertext and Performance", in PMC/PostModern Culture vol. 12-1, 2001. (http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/pmc/v012/12.1raley.html) [full text: doi:10.1353/pmc.2001.0023]

Rasula, Jed & McCaffery, Steve. Imagining Language. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1998.

Ricardou, Jean. Problèmes du nouveau roman. Paris: Seuil, 1967.

Roche, Maurice. Compact. Paris: Seuil, 1966.

Sadin, Eric. Sept au carré, Paris-Bruxelles: Les Impressions Nouvelles, 2002.

Sadin, Eric. After Tokyo (multimedia project), (2004) available at: www.aftertokyo.org.

Sadin, Eric. Tokyo, Paris: P.O.L, 2005.

Van Looy, Jan & Baetens, Jan. Close Reading New Media, Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2003.

Williams, Raymond. Television. Technology and Cultural Form. New York: Schocken, 1975.

Winston, Brian. Media Technology and Society: From the Telegraph to the Internet. London: Routledge, 2000.