Volume 5 Issue 1 (2016) DOI:10.1349/PS1.1938-6060.A.459

The Rise and Fall of the Television Broadcasters Association, 1943–1951

Deborah L. Jaramillo

In 1952, Harold E. Fellows—then president of the National Association of Radio and Television Broadcasters (NARTB; known until 1951 as the National Association of Broadcasters, or NAB)—described the NAB's history as a series of stabilizing efforts.1 From the NAB's formation in 1922 to its struggles with the impressive growth of radio stations, the blossoming of television, and the entrance of FM, the trade association had emerged as a unified front. "Stations, networks, manufacturers, and special services have closed ranks," Fellows remarked. Fellows referred to the unification of radio and television within one organization as a "noble experiment," but it was clearly an economic boon. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) had frozen the approval of TV license applications in 1948 in order to fix its channel allocation plan, but UHF and color TV hearings prolonged what should have been a brief suspension of industrial growth.2 As of July 1, 1951, 107 television stations were in operation, and 415 TV station applications awaited approval from the FCC.3 Even in the midst of the freeze, over 14 million television sets were in US households.4 By 1952, the year the FCC ended the license freeze, the NARTB would be poised to oversee television's expansion.

Television histories do not address the NAB's difficulties with television, so the historiography would leave one believing that television had been a fixture of the association since its development, or at least since the beginning of full-fledged commercial operations. In fact, the NAB paid scant attention to television throughout the 1940s. In a sense, television was put on hold for the duration of the United States' involvement in World War II, and manufacturing and most broadcasting did stall. While CBS left television broadcasting from late November 1942 to early May 1944, and DuMont Laboratories went dark briefly beginning in mid-1943, NBC stayed on the air in a limited fashion throughout the war.5 The industry did not stop from 1941 to 1945; its interrelated components continued to plan, debate, and formulate. That planning drove demand for a trade association to steer and represent industry participants, from the most powerful players to the basic units of broadcasting: the local stations. The result was the Television Broadcasters Association (TBA)—an organization deserving its own place in broadcast history.

Using archival documents from the Library of Congress's National Broadcasting Company history files and the Wisconsin Historical Society's National Association of Broadcasters Records, this article centers the trade association within the development and launch of mainstream commercial television, countering the tendency of media scholars to sideline trade associations or to treat the NAB as the inevitable home of the US television industry. Put very simply, the TBA wanted television, and the NAB did not—at least in the 1940s. As an association organized to facilitate the success of radio, the NAB boasted a mature infrastructure and a sizeable AM membership. The TBA was an upstart, a small group of industry elites aspiring to treat television as inherently special and superior to radio. With only five stations in existence at the time of its founding, the TBA lacked a view from the bottom and, as a result, focused on representing the networks and manufacturers. Its challenge was convincing new stations to join when it lacked the station-based management the NAB had spent decades crafting.

Who had television, why they had it, and why that changed makes for a story—long ignored—that highlights the social and institutional entanglements within the web of industry relations. The story also magnifies the tensions between the old and the new. Television was poised to surpass radio in terms of investment, profits, and cultural influence. Although the TBA-NAB conflict exposes the radio industry's hesitation during that moment of transition, it also highlights what the NAB had done correctly. The NAB had integrated the personnel and agendas of radio stations into its structure and governance, and though stations' participation could be volatile, their absence would ensure failure.

A Trade Association by Television and for Television

A persuasive letter from an NAB board member to a station manager in 1948 explained the advantages of belonging to the trade association.6 The station manager—Milton L. Greenebaum of WSAM in Saginaw, Michigan (an NBC affiliate)—asked why he should pay dues to the association and adhere to the NAB's advertising time restrictions when other stations benefited from the NAB's work without the expense of membership. The board member—Harry Bannister of WWJ in Detroit (also an NBC affiliate)—replied that the NAB essentially operated as a crisis-management firm, fighting tirelessly against multiple foes including journalists, religious organizations, intellectuals, women's organizations, the government, music publishers, and the recording industry in general. In a speech in 1950, the NAB's director of government relations Ralph Hardy made the same case in somewhat more dramatic fashion.7 Without a unified and strong association, Hardy said, the antagonists Bannister mentioned would defeat the industry easily. He warned his audience, "I have seen the campfires of the enemy; I have smelled the smoke from their forges where they are fashioning new tools with which to decimate and reduce to impotency the powerful giants of communication which are entrusted to our management." Only the NAB, with a dutiful membership, would stand in their way. NAB leadership hoped this simple explanation would persuade radio stations to stay and, if not already members, to join. The presence of station owners in positions of leadership could also be persuasive; in the NAB, stations looked out for the best interests of stations. Advertisers, manufacturers, and networks were also members, but the NAB could accomplish nothing without the local radio broadcasters.

Early forms of trade associations date back to the 19th century, and radio broadcasters looked to this cooperative strategy to help them fight royalty payments to the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers in 1923. Trade associations form when businesses, having an industry or trade in common, join forces to impact the "conduct of that industry or trade."8 The continued existence of trade associations signals the viability of a regulatory territory situated in between the government and "the spontaneous enterprise of independent business units."9 The cooperation embodied in such associations dwells in between the "extremes" of "unregulated competition" and "authoritative control."10 More than simply being a happy medium, trade associations are, according to Thomas Streeter, one pillar of corporate liberalism, "a set of values" and practices that rests on the belief that government, corporate, and public interests can all be satisfied through their interaction with each other.11 Though interaction is key to corporate liberalism, self-interest propels the formation and preservation of trade associations. Cognizant of the need for a large-scale operation that would protect and self-regulate television as the NAB did, some members of the fledgling industry pursued their own trade association.

Official credit for inspiring television's first trade association goes to Klaus Landsberg, an innovator on the technical and production side of broadcasting.12 Hired by Paramount Pictures in 1941 to launch its Hollywood television station, Landsberg reportedly embarked on a junket in 1943 to garner "support for an organization which would represent the television interests."13 According to a TBA publication, "television interests were disorganized and seemingly getting nowhere" at this time.14 Landsberg was president of the Society of Television Engineers (STE), and that organization formally created the TBA in January 1944 at STE's Chicago convention.15 Landsberg's role in the TBA's formation is illustrative of Paramount's multipronged approach to television investment in the late 1930s and 1940s. As explained by Christopher Anderson, Hollywood studios looked to television's potential to mitigate some of the industrial turmoil already under way.16 Paramount's partial ownership of DuMont Laboratories was emblematic of such a strategy; as Michele Hilmes argues, the DuMont deal was not a random act of diversification. It coincided with the 1938 antitrust suit against the Hollywood studios, so the purchase, for Hilmes, "indicate[d] the direction at least one studio was preparing to take in the event of divestiture."17 Paramount's link to a television trade association through Landsberg and DuMont—an original member of TBA—was further evidence of the studio's comprehensive outlook for the industry.

Although we should remember Paramount as a player in the TBA story, we should not overstate the studio's involvement. An internal NBC memo written by O. B. Hanson, chief engineer and one of the original directors of the TBA, reveals that the RCA Television Committee was actually responsible for creating the association.18 The Television Committee approached RCA chairman David Sarnoff, and Sarnoff signed off on the plans, but, as Hanson wrote, "for obvious reasons the organization of TBA [. . .] came from a source on the West Coast." Hanson went on to explain that some of the TBA's seed money, necessary for the association to take action in Washington on television standards and frequency allocation hearings, came from NBC's three memberships. These three memberships—for NBC's New York, Washington, and Chicago owned-and-operated stations (O & Os)—entitled NBC (owned by RCA) to three votes. The "obvious reasons" for the obfuscation of the TBA's roots likely referred to the need to distance the association from any one company. Landsberg represented Paramount and, by extension, DuMont, but he spearheaded the formation of the TBA in his capacity as president of the STE.19 The TBA could not maintain the appearance of an industry-wide association if its origins could be traced to David Sarnoff's office.

With only ten names on its membership roster, the TBA adopted the slogan "Uniting All People" and illustrated that mission in its seal (Figure 1), which was composed of symbols representing "the rural, the urban, scholastic and industrial." 20

Figure 1: Seal of the Television Broadcasters Association. Photograph courtesy of NBCUniversal Media, LLC. ("TV Progress: A Ready Reference on the Growth and Current Status of TV Broadcasting in the U.S.," TBA publication, Oct. 1, 1950; Folder 611: Television Broadcasters Association 1933–1934; NBC files, LOC.)

The TBA was formed to celebrate television's ability to reach everyone and, more important, to secure the interests of the television industry by learning from the mistakes of early radio.21 To that end, one of its initial goals was to clear any obstacles that stood in the way of nationwide commercial television broadcasting.22 TBA members were acutely aware of the speed with which television would grow once the war ended, so the association "plan[ned] aggressive action" with regard to channel allocation.23 Its first president was Allen B. DuMont (followed quickly by Jacob R. Poppele of WOR-TV, an independent station in New York), and it counted among its early members NBC, CBS, DuMont Laboratories, General Electric, Howard Hughes Productions, and Television Productions Inc. of Hollywood.24 As the TBA matured, it formed committees on each of the following aspects of broadcasting: advertising, station operation, public relations, programming, education, and membership. Much like the NAB, the TBA sent its members a weekly bulletin with industry updates.25 The TBA also convened monthly to remain abreast of industry developments and, similar to the NAB, held regular conferences.26

TBA rhetoric relied heavily on its uniqueness as a consequence of television's newness. One TBA publication (Figure 2) describes the television broadcaster as a pioneer "with no precedents to follow—except those that might have been set for related industries—and many of these do not apply." 27

Figure 2: TBA publication. Photograph courtesy of NBCUniversal Media, LLC. ("TV Progress: A Ready Reference on the Growth and Current Status of TV Broadcasting in the U.S.," TBA publication, Oct. 1, 1950; Folder 611: Television Broadcasters Association 1933–1934; NBC files, LOC.)

Without mentioning radio by name, the TBA distinguishes television as "new ground" that requires new knowledge wholly distinct from the earlier medium. Because the association formed so early, TBA president J. R. Poppele argued in one 1947 report that "no precedents had been set to hamper its free growth and expression. Starting from scratch, as such, we are better able to guide our destinies than if we were hamstrung with antiquated precedents and 'musts.'"28 Poppele's words were not as concerned with radio as they were concerned with the NAB. Refusing to see the NAB's past as a model for its own operations meant that the TBA was free to pursue the interests of television without giving much thought to radio. It was also free to avoid adopting the NAB's counterproductive measures, such as the multiple radio codes that sought to police radio content. Considering the strong ties its members had to radio, and understanding how connected radio was to television in matters of regulation and advertising, one could argue that Poppele's statements amounted to empty rhetoric. However, as the years passed and as the TBA needed to attract more members to stave off encroachment by the NAB, Poppele's words transformed from the bluster of a young upstart into the rallying cry of a hardworking yet endangered institution. In 1950 Poppele insisted on the TBA's track record and value in the face of low membership numbers:

TBA's fine record of accomplishments since it was founded in 1944 should commend itself to all broadcasters who are not now affiliated with the Association. TBA's greatest asset has been its ability to speak without qualification for television broadcasters only. Since it has been so vocal—and has done its job so well, despite financial limitations—it deserves the unqualified support of the industry [emphasis original].29

Indeed, the TBA accomplished much for the early television industry with little recognition and support, and the following section provides three examples of this work.

The Fight over Frequency Allocations

As early as August 1944, the TBA focused on influencing the outcomes of the FCC's frequency allocation hearings, drafting a set of "allocations principles" aligning specific channel assignments with proper television service in the public interest.30 Not only was the TBA a fixture at FCC hearings, but its engineering committee chief also directed the FCC's Special Industry Committee on TV Allocations.31 Acceptance by the FCC prompted the TBA to describe itself as the "official voice of the television industry in the United States."32

Securing exclusive spectrum space for television meant that the TBA needed to participate in the debate over frequency modulation (FM) radio allocations. Lawrence D. Longley writes that FM's history has come to be understood as a battle between FM and TV, but that fight is actually not as clear-cut as the narrative of competition implies.33 A 1930s innovation, FM radio offered listeners improved reception—a mark of superiority that had the potential to disrupt the networks' control over radio and to serve rural audiences out of the reach of AM signals.34 Despite FM's promise, the FCC virtually ignored it for reasons related to the radio engineering status quo and the limited resources available to the FCC to test the viability of the technology.35 As Vincent Mosco argues, the FCC's limitations made it dependent upon research conducted by RCA, which had considerable investments in both AM radio and the new field of television.36 Even when the FCC allocated spectrum space to FM in 1940, the commission was determined to situate FM as a "secondary" service to commercial AM radio.37 After halting FM licensing from 1942 through the end of World War II, the FCC reconsidered its 1940 allocations and proposed moving FM service to a higher band to avoid interference, much to the disappointment of FM proponents.38 In the ensuing allocation hearings, two distinct groups with allegedly opposing interests emerged: TV interests and FM interests. This stark division did not hold; before the FCC finalized its FM allocations, the TBA aligned itself with the FM Broadcasters, Inc., and requested a lower band for FM.39

Although Longley does not explain why the TBA shifted its allegiances in this way, TBA documents indicate that the association sided with FM interests to locate FM radio within 50–68 megacycles because this plan, known as "alternative plan #1," located TV at 68–74 mc, 78–108 mc, and 174–216 mc.40 These bands existed firmly within the very high frequency (VHF) range of the spectrum. Not surprisingly, RCA also sided with FM in order to protect its stake in VHF.41 Both the TBA and RCA leaned on the excuse that tampering further with TV and FM allocations would stall the postwar development of TV.42 Alternative plan #1 failed, and FM radio moved to 92–106 mc, but TV allocations in VHF expanded.43 It should be noted, though, that the TBA was not opposed to UHF television allocations as RCA and DuMont were. According to its own "allocation principles" drafted in 1944, the association proposed that television be allocated channels at 40–250 mc (in VHF territory) and at 400–2000 mc (in UHF territory).44 Later, in 1949 (early in the license freeze), the TBA's Engineering Committee proposed "full utilization of UHF" while the FCC reconsidered TV allocations.45 This decision may have brought the TBA into conflict with RCA, which may, in turn, have exacerbated tensions between the TBA and the NAB. Conflict with the NAB was already present as early as 1946 when the TBA successfully opposed the NAB's proposal to revisit FM allocations and claim channels already allocated to TV.46

Alleviating Threats to Manufacturing

The TBA's activities reflected the concerns of its members, but with few television stations actually on the air in 1946, the association directed its attention to the health of manufacturers. By early 1947 the association counted among its members a number of "leading manufacturers of television equipment," a constituency affected by postwar labor unrest and attendant material shortages.47 Reflecting on the TBA's progress in 1946, TBA president J. R. Poppele noted that the number of television sets manufactured fell short of earlier predictions because of these shortages and because the industry was "starting from scratch" with "no moulds or dies or previous know-how to make a resumption of manufacture a relatively simple procedure."48

Also impeding manufacturers' progress was a problem relating to television antenna installation in apartment buildings in New York City.49 Antennas cluttered rooftops and interfered with picture quality, so by March 1947 landlords refused to allow antenna installation until a "master system" was created.50 As Lynn Spigel notes, DuMont and RCA began marketing television sets to consumers in 1946, signaling a transition from the public exhibition of television to its private, home-based consumption.51 Eager "to tap into and promote the demand for luxuries," television manufacturers needed not just homeowners but apartment renters, particularly in New York City, to spend their money on sets.52 Recognizing that the landlords' ban affected potentially 2 million families and, consequently, dealt a "serious blow to manufacturers and servicing companies affiliated with TBA," the association created its Sub Committee on Apartment House Television Installations and submitted to the Real Estate Board of New York a plan to resolve the problem while manufacturers could design a master antenna system.53 By December 1947 the TBA Engineering Committee had approved two systems, and one was put to use immediately.54

Noteworthy, too, was the TBA's success in staving off a 20 percent amusement tax or "Cabaret Tax" on television sets used in public establishments. Implementation of the tax would have hampered the sale of sets to bars, for example—a possibility that drove some sponsors to "withhold contracts for televising big league games" until the matter was settled.55 Poppele met with Joseph Nunan of the Internal Revenue Service to convince him that television approximated radio more than it resembled "cabaret entertainment."56 Poppele also reminded Nunan that television's public service role complicated its classification as "strictly an 'amusement.'" The IRS concurred and exempted TV from the tax.57

By the end of 1947, Poppele was convinced that the TBA had risen in "stature" because of its "initiative and progressive actions."58 Evidence shows that the TBA championed television relentlessly in major and seemingly minor ways. In 1947 the TBA convinced the New York Times to carry television listings on Sundays.59 In 1948 the association officially protested the rates AT&T and Western Union were charging the networks for interconnection.60 And in 1950 the TBA successfully testified against the Department of the Treasury's proposed 10 percent excise tax on TV sets.61 Examples like these demonstrate the TBA's will to reflect "the majority view of the industry."62 Nevertheless, the organization's decisiveness on matters relating to frequency allocations and manufacturers' and networks' financial well-being did not hold up when the conversation turned to television content.

Managing Moral Responsibilities

Anxieties about program content—apparent even before the widespread launch of mainstream commercial television—factored into the TBA's early plans for television. This type of anxiety followed the tradition of "moral panic" that accompanied the rise of "commercial amusements" in the early 20th century.63 Spigel notes that reformers clamored for "codes of decency" in motion pictures and their exhibition venues.64 Whereas entertainment in the public sphere triggered concerns about content, broadcasting as a "mechanized amusement" for the private sphere inspired "hopes for salvation."65 The cultural sentiment Spigel describes coincided with early conceptualizations of broadcasting quality. According to Philip Sewell, early discourse about radio and television quality centered on "institutional form, practice, and structure" rather than on "conventional conceptions of content."66 Therefore, the theme of morality was less prevalent in the 1930s than in the 1940s and 1950s. The TBA's conversations about content as early as 1944, then, marked a telling transitional moment—one in which form and content commingled as notions of decency began to creep into the preoccupations of the early television industry.67

The TBA drafted a detailed television code in July 1945 but never ratified it.68 In 1946 the Program Committee worked on revising the initial code without formulating concrete plans for its adoption and enforcement.69 The association's attitude toward such a code centered on "moral responsibilities," but its appreciation for television's infancy tempered any zeal to mandate standards. Poppele wrote in 1947 about shielding the medium's "vigorous experimentation" from "namby pamby do's [sic] and don'ts."70 In the same report, though, Poppele encouraged TBA members to "[endorse] the idea of adopting some form of guide or code [. . .] until such time as a more permanent code can be adopted." Poppele wanted the TBA to embrace a sense of responsibility while avoiding the complications of a code—complications made evident by the repeated failures of the NAB to enforce its radio codes.71 Noran E. Kersta, a TBA Code Committee member and manager of the Television Department at NBC, even stated that any code "accepted by the TBA Directors would never have unanimous acceptance or approval by the TBA membership."72 Still without its own code in 1948 and hesitant to stifle experimentation with "sight and sound," the TBA crafted "general principles of programming service" and distributed the 1948 NAB Standards of Practice and the Motion Picture Production Code for use by stations.73 This decision (or indecision) conformed to Poppele's belief that a "guide" should precede a concrete code.74 TBA correspondence indicates that the association knew a code was a losing proposition, especially so early in television's development. According to one letter, a TBA code needed to be "simpler" than the 1948 NAB code—a sentiment that supported the recurring idea that experimentation needed to be free from the type of censorship that could result from moral panic.75

The TBA represented itself as a television-only club despite some of its members' involvement in radio, and it had the makings of a strong association but for its existence in the shadow of the larger, older NAB. As it mimicked the NAB—though certainly on a diminished scale—it operated for four years outside of the NAB's competitive gaze. The TBA's most vexing problem was its small membership, a necessary evil because of the few television stations in existence. Stations, rather than networks, stood to benefit the most from routine and extraordinary trade association actions. Radio stations in particular stood to lose if television interests competed with their own, but for radio stations moving into television service, the reality of two trade associations was less than ideal.

The NAB Considers Television, Round One: 1947–1948

In 1931 David Sarnoff predicted that television would have a "beneficial" impact on the radio industry, but he took for granted the enthusiasm with which the institutions in place to represent radio broadcasters would embrace television.77 Sarnoff prognosticated later, in 1947, that radio broadcasters who had not ventured into television would see their radio revenue erode following the increase in television viewership. His words eventually reached receptive ears. The NAB began to examine its stake in television first at its annual conference in May 1948. Conference participants expressed "faith that sound broadcasting can live safely and profitably side-by-side with television."78 Both Frank Stanton of CBS and Lewis Allen Weiss of the Don Lee Broadcasting System were optimistic about the new media landscape but noted that AM broadcasting would bear the financial brunt of television during the new medium's formative years.79 The NAB determined that 235 stations—representing only 18 percent of its AM radio membership but responsible for 53 percent of the money the NAB received from its member stations—were moving swiftly to television.80 Of those radio stations, 15 operated television stations, 54 had construction permits to build television stations, and 166 were awaiting word from the FCC regarding their license applications.

The NAB was finally talking about TV, but it appeared to be moving too slowly for Walter J. Damm, vice president of radio and television station WTMJ in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, an NBC affiliate. In June 1948 Damm sent a letter to all television stations in operation, conveying a message of frustration.81 Having run a television station since December 1947, Damm was convinced that neither the NAB nor the TBA was doing much for station operators—operators who suffered from an ignorance of each other's policies, rates, and contracts. The NAB simply was "not concerning itself with television," and the TBA was "doing nothing except what it can on a budget of around $20,000 per year." The formation of the National Television Film Council just five days earlier prompted Damm to ask, "How many more of these associations are we going to have?" His call to action was simple. Station managers needed to get answers from the NAB or from the TBA if the NAB was unwilling to reply. Damm's ultimate solution was for the two associations to merge in order to create a mechanism by which TV stations could share information and standardize their operations.

Damm had experience with just such a merger. In the mid-1940s he was president of FM Broadcasters Incorporated (FMBI). FMBI, which launched in 1940, merged with the NAB's FM branch in 1946, but members did not see special benefits from this enterprise until 1948.82 Damm drew a parallel between that merger and the trouble he foresaw with bringing television into the fold. In a letter notifying NAB president Justin Miller of his missive to all television stations just two weeks before, Damm wrote,

For my part, I would suggest a completely separate section of the NAB, separately financed and staffed and completely undominated by a board of AM broadcasters. This will no doubt be looked upon with considerable disfavor. However, FM's experience has proven the point which I made at the time FMBI and the NAB merged. You cannot expect an AM broadcasters dominated board to look with favor upon spending the money put up by AM broadcasters to service FM or television.83

Television and radio needed to be "under one tent," in Damm's estimation, but the two needed to be segregated to circumvent the AM domination Damm feared. Pushing for a speedy resolution, Damm also recommended a name change if the NAB decided to adopt TV.

The stations' responses to Damm's initial letter (at least the responses he forwarded to Miller) expressed doubt about the TBA's efficacy, due mostly to its financial constraints, and opted for an NAB-led enterprise. Miller appreciated Damm's efforts and agreed that the NAB needed to move on the television issue.84 As to Damm's doubts about AM's feelings, Miller wrote, "even the AM operators are becoming interested in television so rapidly that I think we will have little difficulty in getting action at the next meeting of the Board." Miller anticipated three possible courses of action: (1) initiate activity by the NAB board, (2) amend the NAB bylaws to incorporate television into the structure of the NAB, and (3) pursue a "coordination" with the TBA as the NAB had with FMBI. "I am doubtful as to whether this would be feasible," Miller wrote, "as there seems to be considerable pride of prestige in the present TBA organization." This was not the last time someone from the NAB would remark on the TBA leadership's attitude. Damm shared Miller's pessimism about a merger.85 Nevertheless, Miller and Damm agreed to set up an August meeting wherein television station managers could meet and discuss how to move television forward within a trade association framework.

In anticipation of the meeting of television stations on August 11, 1948, Miller fashioned a Board of Directors Television Advisory Committee (TAC), which would determine how best to fold television into the NAB.86 But first the television stations needed to meet. In attendance were representatives from all five radio and television networks and twenty-three television stations. TBA director George Burbach spoke with mixed feelings.87 After covering the highlights of the TBA's brief history and emphasizing the association's successes despite its underdog status, Burbach aired his skepticism about the feelings and actions of the NAB's AM membership. He felt AM stations would hesitate to share his "deep conviction" that television was "the greatest public service media ever devised," surpassing even radio. More important, a dominant AM membership would have to learn to share the umbrella association, an association that "would have to be prepared to go 'all out' for" television. Burbach concluded by endorsing cooperation between the TBA and the NAB, while Frank Russell of NBC backed a "federation"—an amalgamation of associations representing related segments of the industry—that "would assure a unified front against common enemies." Miller preferred to stick to the practical topic of money. NAB's budget far exceeded that of the TBA, and any attempt by the TBA to match the resources of the NAB—an impossible task—would only result in redundant services. Stanley Hubbard, a broadcaster from Minnesota, raised the issue of industry standards, citing reports of a TBA code and warning of "conflict and confusion" if broadcasters had two different sets of standards to negotiate. The August 9 issue of Broadcasting reported that the TBA was in the process of drafting a TV code but named no completion or adoption date.88 The article also stated that Poppelle "took lightly" any talk of the TBA's absorption into the NAB; he favored cooperation. Summing up the August meeting, the NAB's press release touted the "industry progress and great economies" that attendees agreed cooperation between the TBA and the NAB would bring.89 The two groups would proceed by forming two three-person committees to investigate such cooperation.

The TAC met in Chicago just two days later to discuss the role of television within the NAB. The results of that meeting, at which Harry Bannister was elected chair, ensconced television within the protective bounds of the NAB, if informally. The TAC argued that the creation of a "complete television trade association service" was the NAB's "absolute duty."90 The rationale for this new development grew out of calculations about radio's future. Because radio broadcasters would fund television's launch, the NAB needed to commit itself to the new pursuit of its primary membership. The NAB would not forget the TBA as it forged ahead; the TAC promised to work with the television association "to achieve unity." The TAC also put forth two resolutions to solidify television's place within the NAB. The first would put television members on equal footing with radio broadcasters and ensure television representation on the Board of Directors. The second, echoing the resolution from the August 11 meeting, would form two three-person committees to determine how the NAB and the TBA would move forward together.

The TBA and NAB committees met on September 1, 1948.91 A. D. Willard Jr., vice president of the NAB and a member of the NAB's three-person committee, reported back to NAB president Miller after the meeting and laid out two options: cooperate or compete.92 He doubted the viability of cooperation, describing the TBA delegation as "extremely sensitive people who are inclined [. . .] to place personal matters ahead of industry welfare." The NAB was an entrenched trade association meeting with a much younger and much smaller organization. That Willard detected some defensiveness on the part of the TBA's leadership may have been a misinterpretation of a considerable power imbalance.

The NAB-TBA plan that emerged from the committees' follow-up meeting in October detailed administrative, membership, and financial structures.93 The NAB and TBA would maintain their separate structures, but the two associations would share a treasurer, and two members of each board would serve on the other's board. The plan also delineated the roles the two associations would play. The TBA would stop being a full-service enterprise and instead would take charge of "representation of television interests in the controversial fields of TV promotion, TV allocation and TV legal representation." The NAB would simply extend to television what it had already performed for its radio membership: "regular trade association service in non-controversial areas in the fields of sales promotion, advertising, research, labor relations, public relations, programming, [and] legal (where it is non-controversial)." One upside, besides the legitimation of television within the NAB, would be the windfall from new TV members—a $25,000 to $30,000 boost to the NAB-TBA coffers.

Less than one month after the formulation of the NAB-TBA plan, the NAB board directed a new committee to conduct a big-picture study of the NAB operations.94 A "realignment" was proposed to confront "the problems in all fields of electronic mass communication in order to provide adequate representation and service to all such interests."95 TV and FM's accelerating momentum spurred the study, but the consequence of this new resolution was the postponement of two major TV-related developments: the creation of the NAB's Television Department and the NAB-TBA merger. "The TBA cooperation project is not out the window," Broadcasting stated, but it had stalled indefinitely.96

The TBA held its annual clinic in December, and after J. R. Poppele was elected to his fifth term as president, he spoke about the TBA-NAB merger plans. Evincing the "pride" and "sensitivity" that the NAB leadership commented upon negatively, Poppele stated, "Your directors are of the firm conviction that TBA must never lose its autonomy and that your industry problems can best be handled in an atmosphere where television—and only television—is the object of one's particular interests."97 He then revealed that the TBA-NAB merger plan was just about to be approved by the TBA board when the NAB announced its realignment study. Poppele positioned the TBA as acting in the "best interest of the television industry" when the NAB abruptly aborted the plan.98 Significantly, the TBA board vote would not have been unanimous; Allen B. DuMont (who Broadcasting aptly noted had "no alliance with sound broadcasting") opposed the merger on the grounds that "the television broadcasters and manufacturers [could] put their best foot forward only through an organization exclusively devoted to the espousal of the visual cause."99 The year 1948 ended with the TBA digging its heels into a landscape dotted only with television sets. Perhaps trying to appease the majority of its members, the NAB waited.

The NAB Considers Television, Round Two: 1949

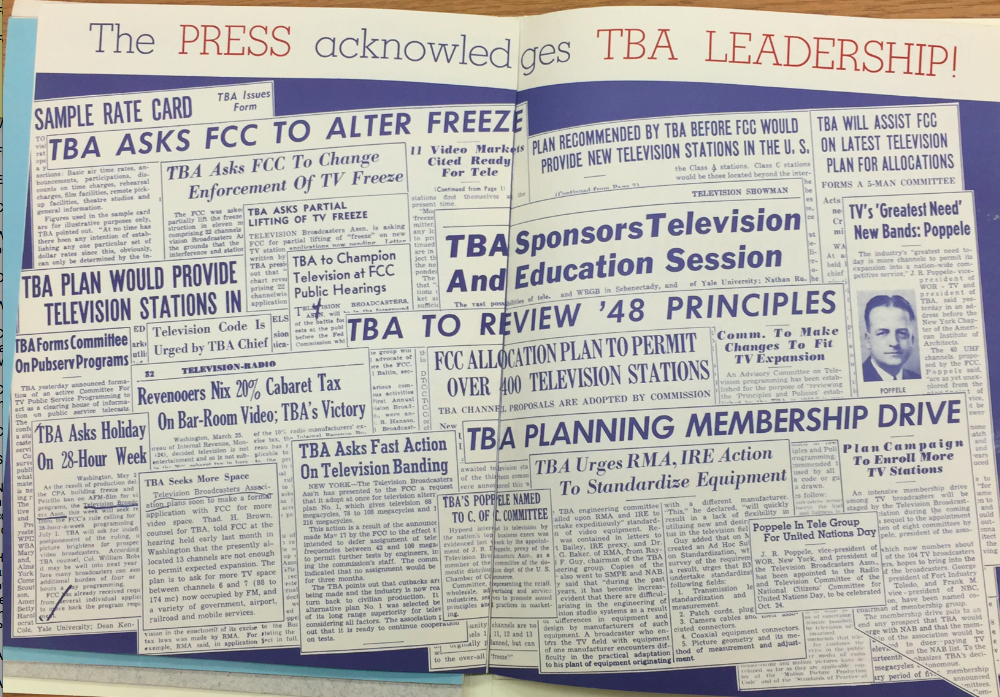

The TBA exploited the NAB's hesitation deftly, implementing changes that attempted to bring its services on par with the NAB's. In February 1949 the TBA announced the addition of three new member services.100 These services included a "monthly program exchange service to provide a complete list of new programs on member stations," "quarterly 'status of the industry' reports," and monthly reports of regulatory and legislative actions. The TBA also planned to update members regularly on license and construction permit applications as well as station personnel. Finally, the TBA was moving toward the fulfillment of Damm's wish list of items for television stations: the formation of committees to handle issues such as copyright and advertising rates. Two months later, Poppele continued to emphasize TBA excellence at the NAB convention (Figure 3). In a statement to attendees, Poppele celebrated television's rapid growth. Noting inevitable complications for the television industry, Poppele remarked that the TBA "from the outset has recognized these problems and today is in a far better position to wrestle with them than ever before, by virtue of its dominance in television. By cooperative action with other groups interested in the welfare of the industry, the TBA will do the job [emphasis original]."101

Figure 3: Collage of the TBA's accomplishments as covered by the trade press. Photograph courtesy of NBCUniversal Media, LLC. ("A Pledge to Television Broadcasters," TBA publication, 1950; Folder 611: Television Broadcasters Association 1933–1934; NBC files, LOC.)

Two developments in May continued to pit the TBA against the NAB's entrenchment. First, the NAB board voted to install a director for its TV department.102 Recall that the NAB postponed the creation of that department during its realignment study; although the NAB apparently followed through on the TV department, it did not restart merger talks. As the NAB board decided on a director, the TBA openly courted FCC chairman Wayne Coy for the presidency of the TBA—a newly created, salaried position based in Washington and tailored to improving public and governmental relations.103 The TBA consistently described its relationship with the FCC positively, so its pursuit of Coy is unsurprising.104 Its willingness to spend the money was surprising. The TBA was a cash-strapped organization, so DuMont was to raise the necessary funds for the three-year appointment by appealing to television manufacturers.105 Broadcasting speculated that this sort of expansion would incite the NAB to pursue television "aggressively."106 At the time, the NAB counted only six television stations among its 1,838 members—three more TV stations and eighty-one fewer radio stations than in 1948.107

In June 1949, Sponsor magazine—an advertising trade publication—pointed out the flaws in the NAB's treatment of television. Calling for a federated NAB, the trade magazine likened the NAB's "absent" treatment of television to that of FM radio.108 Using AM station dues to fund a competitor was simply too unpalatable to the NAB membership. "The result," Sponsor wrote, "is an association (Television Broadcasters' Association) which month by month is becoming a more important factor in the visual air advertising field." Citing the failure of the NAB to incorporate the TBA, the article lamented the "divided" state of broadcasting, which had three associations: one for AM radio, one for FM radio (the FM Association, or FMA), and one for television. This situation was simply bad for business, as it fostered division when these media had interests in common.109 The article proposed that AM, FM, and TV each have a board of directors with separate dues structures, and all would operate under a "Federated President."110 Though "internal politics" would be inevitable, Sponsor believed the status quo was too shortsighted in the face of technological development.

Broadcasting's own research department polled broadcasters and found that just over 50 percent favored a plan to reorganize the NAB into three departments—one each for FM, AM, and TV.111 Just over 24 percent of broadcasters preferred a merger with the TBA. NAB president Miller acknowledged these statistics and the "many pressures" placed on the NAB "to get into television" in a letter to a station executive just two days after Broadcasting's poll was published112. These statistics may have been on Miller's mind when he met with the heads of the four national radio networks on July 21, 1949, at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York City to further explore the topic of television. Frank Stanton and Earl Gammons from CBS, (former FCC chair) Charles R. Denny from NBC, Mark Woods and Robert Kintner from ABC, and Frank White from MBS weighed in on the NAB's trials with the TBA. Kintner, who was also a TBA board member, explained that the NAB's refusal to merge the two associations had upset the TBA's leadership.113 Miller explained that the NAB board had not explicitly refused; they had simply not figured out how to move forward on the television issue. Because the NAB had a policy forbidding it from promoting one branch "in derogation of other branches of the industry," Miller proposed that the roles of the NAB and the TBA should be distinct: the NAB would be a "full service operation for television," and the TBA would confine itself to promotion, sales, and government relations.114 We can begin to see why the TBA, which had recently expanded to function more like a full-service operation, would not agree to such a division of labor. Stanton, Denny, and Woods agreed with Miller's proposal and opposed the creation of an entirely separate trade association for television.

By August 1949 the NAB began to envision itself as an "all-industry association" with audio and video divisions serviced by all of the association's departments.115 As the NAB reorganized its structure, it abandoned the idea of a merger with the TBA116. Crucially, with only six television members, the NAB could not create an autonomous television branch. Instead, Miller planned to treat TV like FM—"as a service organization and with proportionate representation on the NAB board."117 The TBA would continue to be the organization that promoted TV—much as the FMA handled FM broadcasting—but the NAB would not engage in promotion because it was dominated by AM broadcasters. Signs in August that both the FMA and TBA were ramping up their operations did not seem to interfere with the NAB's plans for a "comprehensive" FM and TV operation.118 The NAB's ambitions were bolstered by news in late August that NBC's O & Os were set to join the new TV division.119 In fact, the NAB was ramping up its own TV operation with a dramatic increase from six to thirty-two TV members (of seventy-eight TV stations in operation) in September.120 The NAB managed to lure the bulk of these members, which were affiliated with existing AM members, by discounting their dues ($10 per month) until January 1, 1950.121 The association was not just luring members away from the TBA; it also poached the TBA's vice president, G. Emerson Markham, for the position of Video Division director in early September.122

NAB Internal Strife: 1949–1950

Markham's departure from the TBA colored the NAB's behind-the-scenes membership troubles in a personal way. Network participation in the NAB had not been steady, and radio station membership fluctuated, too. In June 1949 several large radio stations—all NBC affiliates—left the NAB, which led Miller to hypothesize that these particular stations needed to "cut corners" to accommodate their large investments in television.123 Stations were not the only businesses blaming their departure on financial difficulties. In a letter to Miller, ABC's Mark Woods also mentioned "expense" as one reason the network was looking to sever its ties to the NAB; ABC's most recent bill from the NAB was $5,000.124 In reply to Woods, just one day after Miller met with network heads at the Waldorf-Astoria, Miller articulated his realization that network happiness depended on television station "expansion," and that the NAB had a major role to play in facilitating that. In other words, one way to keep the networks on the membership roster was to advocate for television.

In February 1950 Miller felt sufficiently threatened by the possibility of the networks resigning from the NAB and taking their owned stations with them that he wrote to the NAB Board of Directors to ask "how far the NAB should go in an effort to perform services of particular value to the networks and to their owned stations."125 Money again was an issue. The combined network and owned station contributions amounted to $7,731 per month, which Miller pointed out was just a little under the amount contributed by 625 radio stations. Such a financial hit would disturb the very structure of the NAB. Miller also worried that the networks' affiliates might follow suit. The majority of responses to Miller's query assessed that the cost of network abandonment was too great to deny the networks special services.126 Other board members relayed exasperation. Citing the networks' power to "get practically anything they want" and the need to treat all members equally—from the largest network to the smallest independent station—these dissenters did not want to be held hostage by elite bodies interested only in services pertinent to themselves.127 One board member, Harry R. Spence, posed this prescient question: "Are they satisfied with the NAB television department?"128

Miller believed NBC would stick with the NAB, but he was less confident about ABC and CBS.129 Robert Kintner, president of ABC, was a TBA board member and, according to Miller, "probably resent[ed] a little [the NAB] pulling George Markham away from TBA." Both Kintner and Frank Stanton, president of CBS, were concerned about money, and Joseph Ream, executive vice president of CBS, had a number of reasons to leave the NAB. Miller felt these reasons were exaggerated, though, and stated that CBS simply did not "want a strong NAB." CBS resigned from the NAB on May 18, 1950, and ABC followed on May 26. Both took their owned stations with them; CBS had seven, and ABC had five. The NAB stood to lose $40,000 per year from CBS and its stations, as well as between $25,000 and $30,000 from ABC and its stations.130 Although CBS officially attributed its resignation to redundancies across the network's and the NAB's functions, Miller dismissed these excuses and called the networks "selfish," characterizing them as ungrateful opportunists who were "passing on to their affiliates [. . .] the burden of maintaining their trade association just because they think there are no immediate pressing issues."131 Miller also faulted Kintner for being too sensitive, because he felt that the NAB's new Standards of Practice "unjustly classified ABC's programs as below standard."132

This NAB-network turmoil was indicative of the general upheaval surrounding TV. In 1949 television was on the verge of occupying a central place in US social and economic life. The 1949 revenues for the television industry amounted to just over $34 million, "almost four times the 1948 amount" according to the FCC.133 And, in late 1949, the NAB became aware that the 1950 Census would include a question about television set ownership.134 The signs of television's import proliferated, but the NAB had yet to move television beyond the committee level. The NAB Television Committee, chaired by Robert D. Swezey of ABC affiliate WDSU-TV in New Orleans, operated strictly in an advisory capacity, meeting biannually to review the processes and policies of the NAB as they pertained to television.135

Toward the NARTB

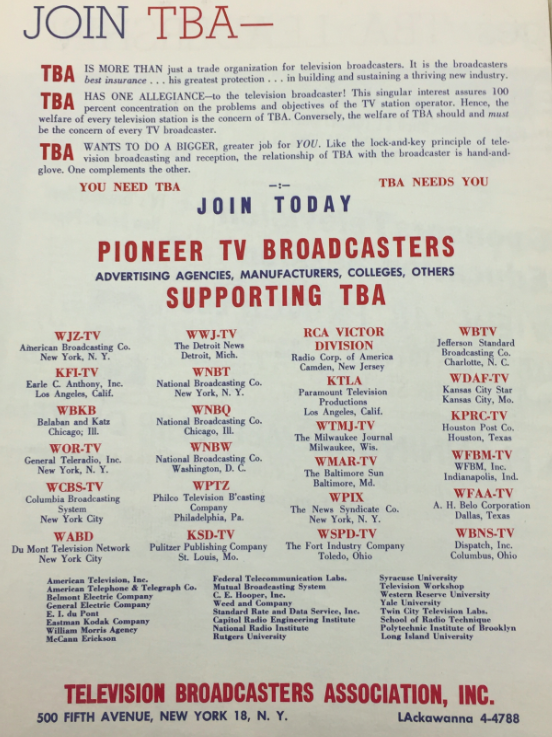

Before the NAB decided to promote television within its organization, the TBA, emboldened by its new 10-point "pledge to the industry" (Figure 4), launched a massive membership campaign in June 1950.136

Figure 4: TBA publication. Photograph courtesy of NBCUniversal Media, LLC. ("A Pledge to Television Broadcasters," TBA publication, 1950; Folder 611: Television Broadcasters Association 1933–1934; NBC files, LOC.)

The pledge consisted of ten goals for 1950, including ending the license freeze, monitoring broadcasters' programming "responsibilities," and opposing unfair government intervention.137 The new "10-point program" represented a financial commitment to the industry's well-being that required more support from station operators than it currently had.138 In 1950 the TBA still counted only thirty-five stations—about one-third of television broadcasters in operation—among its dues-paying members (Figure 5). This situation meant that a handful of television stations were subsidizing work that supported all television stations. By contrast, approximately 1,500 dues-paying radio members of the NAB subsidized the work that benefited its thirty-seven TV members.139 Faced with this disparity, the TBA planned to make personal appeals to all nonmember stations.140 The campaign was a public relations push of sizeable proportions, and it did not go unnoticed.

Figure 5: Abbreviated list of TBA members in 1950. Photograph courtesy of NBCUniversal Media, LLC. ("A Pledge to Television Broadcasters," TBA publication, 1950; Folder 611: Television Broadcasters Association 1933–1934; NBC files, LOC.)

At the fall 1950 (August 31–September 1) meeting of the NAB's Television Committee, item number 2 on the agenda was the "place of the TV department in the Association," indicating that television station operators were not going to be content simply with an advisory committee.141 One station president, Campbell Arnoux of NBC affiliate WTAR in Norfolk, Virginia, wrote to Miller in early November 1950 to campaign for the creation of an "autonomous [television] group with its own sub-board of directors, its own dues schedule and committee."142 Chiding Miller for the NAB's "inadequate" service, Arnoux called for immediate change lest the NAB "lose the TV stations to the TBA."143

By mid-November 1950, the NAB Board of Directors decided to act on the television resolutions adopted at various NAB district meetings earlier in the fall.144 Robert D. Swezey, chairman of the NAB TV Committee, submitted the committee's proposal to the NAB board and added this justification: "There is purpose now, as television stations move into the profit columns, in establishing a sound economic basis for their continued membership in the NAB and the definition of a procedure which will give television members necessary independence and flexibility of action."145 The NAB board resolved to establish "a separate TV Board of Directors [. . .] to operate within the framework of the NAB, but to have complete autonomous authority to determine its own dues structure and to formulate its own policies with respect to all questions relating to television."146 The resolution called for the NAB's TV members to convene to sort out the details, and it created yet another committee to bring the recommendations of the upcoming convention to the NAB board.147

One day after the NAB board adopted this resolution, the NAB sent telegrams to all of the TV stations in operation—not just NAB members—notifying them of the development and assuring them that its adoption would entitle TV members to all of the NAB's services.148 In the letter that followed the very next day, NAB TV directors Swezey and Eugene S. Thomas elaborated on the previous day's telegram and again included all station operators in the mass mailing.149 The NAB's inclusion of nonmembers in the sharing of this news was a shrewd tactic; by notifying all TV stations of this dramatic change, the NAB graciously welcomed all the holdouts and their purses. The NAB estimated that a revised dues structure that included new and existing TV memberships would net the association anywhere from $89,000 to $114,000 per year.150 Earlier in 1950 the NAB had encountered a membership crisis when many poorer-funded stations departed because of a dues increase and general "dissatisfaction" with the association.151 In February the NAB counted 1,150 AM members, but this dropped to 940 in August.152 Membership numbers rebounded, though, and as of November, the NAB counted 1,457 total members representing AM, FM, and TV stations.153 Apparently sensing momentum, the NAB launched a public membership campaign at the beginning of November, but board members had already been conducting their own outreach program called the "One Call Club," in which each board member and other the NAB higher-ups made personal calls to stations.154

In spite of the uptick in membership, Swezey and Thomas pointed out in their letter to television stations that the "token" amount collected from TV members could sustain only "limited service," and that radio members would not look kindly upon the "allocation of any substantial amount of their dues to the furtherance of TV projects."155 Swezey and Thomas were referring to the paltry $10 monthly sum that TV stations paid if they were attached to AM member stations.156 According to the letter, two NAB district meetings adopted resolutions to create distinct television and radio groups within the NAB, and those resolutions spurred the NAB's adoption of its own resolution.157 The letter further characterized the resolution as "an initial, and in [the NAB's] opinion, a timely step to provide for the first time adequate service, representation and flexibility of action for its TV members, without embarrassing or burdening its aural broadcasting membership."158 Expanding its service to television while protecting its radio membership was clearly a priority for the NAB. Although Swezey and Thomas referred to NAB-TV as "timely," many board members felt it was a preemptive strike against the TBA.159

A new committee, headed by Harold Hough of independent station WBAP-TV in Fort Worth, Texas, planned to hold a meeting in Chicago on January 19, 1951, for "television broadcasters from the entire nation [. . .] to see that the expanded, autonomous NAB-TV is set up the way they want it."160 If everything went according to plan at the Chicago meeting, the NAB expected NAB-TV to be fully operational by April 1, 1951.161 Surpassing the purely advisory role of the original Television Committee, the new Television Board would have five primary duties, including the power "to enact, amend and promulgate Standards of Practice or Codes and to establish such methods to secure observance thereof."162 No such code existed yet, but the NAB surely was looking ahead to mounting concerns about the content of television programs.

The companion to the Television Board would be the Radio Board, and the two would complete the structure that Miller anticipated in late 1950.163 Together, these two boards would make up the NAB Board of Directors. Swezey openly doubted the ability of the TBA to compete with what the NAB was proposing. The TBA lacked both the membership and the infrastructure to launch a completely new television trade association on par with the NAB's plan. Doing so would, according to Swezey, "require a minimum investment of several hundred thousand dollars" if the new association were to match the strength of the NAB.164 Although some television operators preferred to see the TBA and the NAB merge, both Hough and Swezey stressed that there would be no such merger.165

The Chicago meeting was a success for NAB-TV, with 75 percent of TV stations in attendance pledging their "unanimous and enthusiastic support" for the new body, which would, in effect, require that everyone "abandon the TBA."166 An editorial in Broadcasting, a publication exceedingly friendly to the NAB, described the atmosphere as one of "almost unprecedented harmony."167 Members displayed overwhelming, if not unanimous, support, voting "by a 15-to-1 ratio" for the new NAB structure.168 An additional marker of success was the high number of stations attending that had aligned with neither the NAB nor the TBA.169 Paramount Television's Paul Raibourn, representing the TBA, warned that "autonomy cannot exist unless each group under the NAB is its own court of last resort."170 Assured that the blueprint for NAB-TV would secure that degree of autonomy, Raibourn announced that the TBA would soon "wind up its affairs."171

Following the Chicago meeting, the NAB rewrote its bylaws to reflect television's new status within the association. The new bylaws created a strong and autonomous Television Board with complete control over all television-related matters, including policies, dues structures, and meetings. The new Television Board would be "its 'own court of last resort.'"172 In a showy bit of rebranding, and recalling Damm's suggestion in 1948, the NAB changed its name "to be more descriptive and to give television and radio equal recognition."173 The NAB officially became the National Association of Radio and Television Broadcasters (NARTB) on April 1, 1951.174 The TBA officially dissolved on the same day. 175

Big changes ensued, and the results nevertheless reflected television's minority status. The new NARTB structure consisted of three boards of directors with the Television Board holding a maximum of fourteen members (compared to the Radio Board's maximum of twenty-five).176 Elected members filled nine seats—one of the seats was filled by Paul Raibourn of the TBA—and representatives from each of the four television networks filled the remainder of the vacancies.177 Television stations without radio holdings had to have a minimum of two seats.178 Miller vacated the presidency in June 1951 and assumed chairmanship of the board, leaving a hole filled by Harold E. Fellows.179 The NARTB anticipated that sixty TV stations would join immediately. Each of the networks was entitled to one membership; the NAB dropouts ABC and CBS were predicted to return to the fold.180 The manufacturer membership of the TBA, meanwhile, was "urged" to add their names to the NARTB roster once the TBA dissolved.181

Why Television, Why Then?

A study of the New York metropolitan area conducted by NBC assessed the growth of television from 1950 to 1951, a period in which circumstances had "drastically changed," according to NBC.182 Indeed, more than 10 million homes had television sets by January 1951, compared with 200,000 three years earlier.183 Two million of those television homes (serviced by seven stations) dwelled within the sixteen counties studied by NBC.184 Among the findings that confirmed the NAB's decision to incorporate television into its association were that TV families made $644 more per year than non-TV families; TV families bought 73.2 percent of new cars purchased within the previous six months; TV families were larger and had younger children; the heads of TV families were younger than heads of non-TV families; more TV families owned telephones, refrigerators, and cars than did non-TV families; TV owners spent 135 minutes of their day watching television, versus 61 minutes listening to radio, 47 minutes reading newspapers, and 11 minutes reading magazines.185 Even non-TV owners enjoyed viewing: the study showed that 59 percent of non-owners watched TV in a month, and 45 percent of non-viewers watched TV in a week.186 When the study combined owners and non-owners, it found that 73 percent of family heads, regardless of set ownership, watched TV weekly.187 These statistics underscored the urgency of the two trade associations' situations.

When we insert the TBA's story into the larger history of television, the collision of old and new media replays through the lens of the trade association—a lens that brings into sharp focus the inseparability of industrial and social relations, the division between businesses that adapt and those that lag, and the centrality of broadcast stations in the development of the television industry. The young association was poised to represent the nation's multiplying television stations and had been toiling for their benefit since 1944. Unwilling to alienate its AM radio membership, the NAB glanced at television now and then, failing to commit to a lasting relationship until AM stations moving into TV pushed the issue.

The details of the TBA's fall and the NAB's internal struggles realign TV history with the basic unit of broadcasting—the station. As integral as the networks were to the NAB's financial health, many of the association's decision makers were local broadcasters. The TBA's inability to attract a majority of television stations meant that stations did not occupy the same political space in the TBA as they did in the NAB. However, NAB documents show that fear of losing network members forced the NAB to admit that the bigger companies were worth special favors. Regardless, the future of the TBA—as a stand-alone association or as a partner with the NAB—hinged on AM broadcasters. As much as the TBA wanted a space dedicated only to TV, the reality of the broadcasting industry bound TV to radio, and the reality of trade associations bound the TBA to stations.

About the Author

Deborah L. Jaramillo is associate professor of film and television studies at Boston University. Her first book, Ugly War Pretty Package: How CNN and Fox News Made the Invasion of Iraq High Concept (Indiana University Press, 2009), analyzed the narrativization, stylization, marketing, and merchandising of the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Her current book project examines the circumstances leading up to the National Association of Radio and Television Broadcasters’ adoption of the 1952 Television Code.

Endnotes

1 Untitled Speech, Harold E. Fellows, Apr. 2, 1952; Folder 9, Speech-NARTB Convention, Apr. 1952; Box 4; National Association of Broadcasters Records (hereafter NAB Records); US MSS 156AF; Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, WI (hereafter WHS). The NARTB once again became the NAB in 1958.

2 William Boddy, Fifties Television: The Industry and its Critics (Urbana and Chicago: U of Illinois P, 1990), 51.

3 Federal Communications Commission Seventeenth Annual Report (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1952), 13.

4 Ibid.

5 Philip W. Sewell, Television in the Age of Radio: Modernity, Imagination, and the Making of a Medium (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2014), 144.

6 Harry Bannister to Milton L. Greenebaum, Nov. 2, 1948; Folder 9: J. Miller, B-General Correspondence; Box 97; NAB Records; WHS. Greenebaum had also asked Bannister about the usefulness of a state-based trade association. Bannister wrote that it might be a "good thing," but that it could "never function in the NAB's field." Greenebaum went on to co-found the Michigan Association of Broadcasters in December 1948. See "MAB Formed," Broadcasting, Dec. 13, 1948, 74.

7 Untitled speech, Ralph W. Hardy, June 23, 1950; Folder 14: Ralph Hardy-General, 1950–1954; Box 5A; NAB Records; WHS.

8 National Industrial Conference Board, Trade Associations: Their Economic Significance and Status (New York: National Industrial Conference Board, 1925), 7.

9 Ibid., 3.

10 Ibid., 315–16.

11 Thomas Streeter, Selling the Air: A Critique of the Policy of Commercial Broadcasting (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1996), 35.

12 Susan K. Wilbur, "The History of Television in Los Angeles, 1931–1952: Part I: The Infant Years," Southern California Quarterly 60, no. 1 (1978): 68–69. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/41170748.

13 Wilbur, "The History of Television in Los Angeles, 1931–1952," 69; "TBA Profile," Television, Oct. 1946, 17.

14 "What Is TBA Doing for the Television Industry?" TBA publication, 1947; Folder 612: Television Broadcasters Association 1947; National Broadcasting Company history files, 1922–1986 (hereafter NBC files), Library of Congress, Washington, DC (hereafter LOC).

15 "Television Broadcasters Assn. Formed by Engineers at Convention in Chicago," Broadcasting, Jan. 24, 1944, 16.

16 Christopher Anderson, Hollywood TV: The Studio System in the 1950s (Austin: U of Texas P, 1994), 37.

17 Michele Hilmes, Hollywood and Broadcasting (Urbana and Chicago: U of Illinois P, 1990), 74.

18 O. B. Hanson to John H. MacDonald, Jan. 30, 1947; Folder 612: Television Broadcasters Association 1947; NBC files, LOC.

19 Prior to his hiring by Paramount, Landsberg was employed by DuMont Laboratories.

20 Television Broadcasters Association, Proceedings of the Second Television Conference and Exhibition, Television Broadcasters' Association, Inc. (New York: Television Broadcasters Association, 1946), 34.

21 Television Broadcasters Association, Proceedings of the Second Television Conference, 36; "Television Broadcasters Association," Television, Spring 1944, 9.

22 "TBA Profile," 17.

23 "Television Broadcasters Assn. Formed by Engineers at Convention in Chicago," 16.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Television Broadcasters Association, Proceedings of Television Clinic of Television Broadcasters' Association, Inc. (New York: Television Broadcasters Association, 1948), 28.

27 "What Is TBA Doing for the Television Industry?"

28 "Annual Report to Member of Television Broadcasters Association," Jan. 7, 1947; Folder 612: Television Broadcasters Association 1947; NBC files, LOC.

29 "Annual Report of the President of Television Broadcasters Ass'n, Inc.," report by J. R. Poppele, Dec. 8, 1950; Folder 611: Television Broadcasters Association 1933–1934; NBC files, LOC.

30 "A Pledge to Television Broadcasters," TBA publication, 1950; Folder 611: Television Broadcasters Association 1933–1934; NBC files, LOC.

31 Ibid.

32 "What Is TBA Doing for the Television Industry?"

33 Lawrence D. Longley, "The FM Shift in 1945," Journal of Broadcasting 12, no. 5 (Fall 1968): 360.doi:10.1080/08838156809386265

34 Vincent Mosco, Broadcasting in the United States: Innovative Challenge and Organizational Control (Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing, 1979), 52.

35 Ibid.

36 Ibid., 53.

37 Ibid., 54.

38 Longley, "The FM Shift in 1945," 356.doi:10.1080/08838156809386265

39 Ibid., 358.

40 "A Pledge to Television Broadcasters."

41 For a detailed explanation of the struggle over UHF and VHF television, see Boddy, Fifties Television, 42–64.

42 See Boddy, Fifties Television, 44–45. See also "A Pledge to Television Broadcasters."

43 Longley, "The FM Shift in 1945," 359–60.doi:10.1080/08838156809386265

44 "A Pledge to Television Broadcasters"

45 Ibid.

46 "Report to the Members of the Television Broadcasters Association," report by William A. Roberts, Jan. 7, 1947; Folder 612: Television Broadcasters Association 1947; NBC files, LOC.

47 "Annual Report to Members of Television Broadcasters Association." Such manufacturers included Farnsworth Television & Radio Corp., Raytheon Manufacturing Company, Philco Corporation, Westinghouse Electric Corporation, and Belmont Electric Company. For a complete list of TBA members in 1947, see "What Is TBA Doing for the Television Industry?"

48 "Annual Report to Members of Television Broadcasters Association," Jan. 7, 1947; Folder 612: Television Broadcasters Association 1947; NBC files, LOC.

49 Ernest A. Marx, DuMont Laboratories' television manager, first brought this to the TBA's attention in a special meeting in December 1946. See "Digest of a Special Meeting on December 19, 1946 of the Board of Directors of Television Broadcasters Association, Incorporated," Dec. 19, 1946; Folder 612: Television Broadcasters Association 1947; NBC files, LOC.

50 "Digest of a Special Meeting on March 13, 1947 of the Board of Directors of Television Broadcasters Association, Incorporated."

51 Lynn Spigel, Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America (London and Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1992), 32.

52 Ibid. Between 1940 and 1950, New York City's population grew from 7,454,995 to 7,891,957. See 1950 Census of Population, prepared by the US Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census (Washington, DC, 1951).

53 "A Review of TBA Activities," Mar. 25, 1947; Folder 612: Television Broadcasters Association 1947; NBC files, LOC.

54 "Annual Report on the Executive Committee on Affiliates to the Members of Television Broadcasters Association, Inc.," report by Ernest A. Marx, Dec. 10, 1947; Folder 612: Television Broadcasters Association 1947; NBC files, LOC.

55 "Annual Report to Members of Television Broadcasters Association, Inc.," report by J. R. Poppele, Dec. 10, 1947; Folder 612: Television Broadcasters Association 1947; NBC files, LOC.

56 J. R. Poppele to Joseph Nunan, Mar. 20, 1947; Folder 612: Television Broadcasters Association 1947; NBC files, LOC.

57 Joseph Nunan to J. R. Poppele, n.d.; Folder 612: Television Broadcasters Association 1947; NBC files, LOC.

58 "Annual Report to Members of Television Broadcasters Association, Inc.," report by J. R. Poppele, Dec. 10, 1947; Folder 612: Television Broadcasters Association 1947; NBC files, LOC.

59 "Minutes of a Special Meeting of the Board of Directors of Television Broadcasters Association, Inc.," Nov. 6, 1947; Folder 612: Television Broadcasters Association 1947; NBC files, LOC.

60 "A Pledge to Television Broadcasters."

61 "A Pledge to Television Broadcasters."

62 "Annual Report to Members of Television Broadcasters Association, Inc.," report by J. R. Poppele, Dec. 10, 1947; Folder 612: Television Broadcasters Association 1947; NBC files, LOC.

63 Spigel, Make Room for TV, 25.

64 Ibid.

65 Ibid., 25–26.

66 Sewell, Television in the Age of Radio, 95.

67 Ibid., 115.

68 Will Baltin to Noran E. Kersta, Aug. 9, 1948; Folder 615: T.B.A.—Code Committee 1948; NBC files, LOC. For the complete 1945 code, see "A Code to Guide the Presentation of Television Programs," Television Broadcasters Association, July 12, 1945; Folder 615: T.B.A.—Code Committee 1948; NBC files, LOC.

69 "A Pledge to Television Broadcasters."

70 "Annual Report to Members of Television Broadcasters Association," report by J. R. Poppele, Jan. 7, 1947; Folder 612: Television Broadcasters Association 1947; NBC files, LOC.

71 For a detailed discussion of the various radio codes and their reasons for failure, see Robert Shepherd Morgan, "The Television Code of the National Association of Broadcasters: The First Ten Years" (doctoral diss., State University of Iowa, 1964).

72 Noran E. Kersta to Ken R. Dyke, George Frey, James Nelson, and H. M. Beville, Sept. 16, 1948; Folder 615: T.B.A.—Code Committee 1948; NBC files, LOC.

73 Code Committee of the TBA to Station Owners, Draft, Oct. 8, 1948; Folder 615: T.B.A.—Code Committee 1948; NBC files, LOC.

74 "Annual Report to Members of Television Broadcasters Association, Inc.," report by J. R. Poppele, December 10, 1947; Folder 612: Television Broadcasters Association 1947; NBC files, LOC.

75 L. W. Loman to Lawrence Phillips, July 30, 1948; Folder 615: T.B.A.—Code Committee 1948; NBC files, LOC.

76 "Television Today and Tomorrow," speech by David Sarnoff, May 18, 1931; Folder 132: David Sarnoff (1930–1935); File 21; Box 9; Library of American Broadcasting Hedges Collection (LAB), College Park, MD.

77 "Television Progress," speech by David Sarnoff, Sept. 13, 1947; Folder 132: David Sarnoff (1945–1949); File 24; Box 9; LAB.

78 "Horizons Unlimited," Broadcasting, May 24, 1948, 23.

79 Ibid.

80 Ken Baker to Justin Miller, memo, June 16, 1948; Folder 9: Justin Miller-Television Department, 1945–1953; Box 112; NAB Records; WHS.

81 Walter J. Damm to Operating Television Stations, June 22, 1948; Folder 2: J. Miller [Board of Directors]-Television Advisory Committee, 1948; Box 112; NAB Records; WHS.

82 Christopher H. Sterling, Cary O'Dell, and Michael C. Keith, eds., The Concise Encyclopedia of American Radio (New York: Routledge, 2010), 306; "NAB's FM-TV Aims," Broadcasting, Sept. 12, 1949, 26.

83 Walter J. Damm to Justin Miller, July 7, 1948; Folder 2: J. Miller [Board of Directors]-Television Advisory Committee, 1948; Box 112; NAB Records; WHS.

84 Justin Miller to Walter J. Damm, July 13, 1948; Folder 2: J. Miller [Board of Directors]-Television Advisory Committee, 1948; Box 112; NAB Records; WHS.

85 Walter J. Damm to Justin Miller, July 16, 1948; Folder 2: J. Miller [Board of Directors]-Television Advisory Committee, 1948; Box 112; NAB Records; WHS.

86 Press release, the NAB, Aug. 6, 1948; Folder 2: J. Miller [Board of Directors]-Television Advisory Committee, 1948; Box 112; NAB Records; WHS; A. D. Willard to Michael R. Hanna, July 30, 1948; Folder 2: J. Miller [Board of Directors]-Television Advisory Committee, 1948; Box 112; NAB Records; WHS.

87 "Report of Meeting, Television Broadcasters and NAB Representatives," Aug. 11, 1948; Folder 2: J. Miller [Board of Directors]-Television Advisory Committee, 1948; Box 112; NAB Records; WHS.

88 "TBA Contemplating Proposal for Code," Broadcasting, Aug. 9, 1948, 48.

89 NAB press release, Aug. 11, 1948; Folder 2: J. Miller [Board of Directors]-Television Advisory Committee, 1948; Box 112; NAB Records; WHS.

90 "Meeting …NAB Television Advisory Committee," memo drafted by A. D. Willard, Jr., Aug.ust 17, 1948; Folder 9: Justin Miller-Television Department, 1945–-1953; Box 112; NAB Records; WHS. See also meeting notes, NAB Television Advisory Committee, August 13, 1948; Folder 2: J. Miller [Board of Directors]-Television Advisory Committee, 1948; Box 112; NAB Records; WHS.

91 NAB press release, Sept. 1, 1948; Folder 2: J. Miller [Board of Directors]-Television Advisory Committee, 1948; Box 112; NAB Records; WHS.

92 A. D. Willard Jr. to Justin Miller, Sept. 15, 1948; Folder 9: Justin Miller-Television Department, 1945–1953; Box 112; NAB Records; WHS.

93 NAB confidential memo, Oct. 25, 1948; Folder 2: J. Miller [Board of Directors]-Television Advisory Committee, 1948; Box 112; NAB Records; WHS.

94 "NAB-BMB Facelifting," Broadcasting, Nov. 22, 1948, 21.

95 Ibid., 74.

96 Ibid.

97 "TBA Election," Broadcasting, Dec. 13, 1948, 34.

98 Ibid., 72.

99 "Coy Approached by TBA," Broadcasting, May 9, 1949, 23, 57.

100 "TBA Expansion," Broadcasting, Feb. 7, 1949, 36.

101 "Statement to the NAB Convention by J. R. Poppele," Broadcasting, Apr. 11, 1949, 46.

102 "Coy Approached by the TBA."

103 Ibid.

104 See "A Pledge to Television Broadcasters." See also "Annual Report to Members of Television Broadcasters Association, Inc.," report by J. R. Poppele, Dec. 10, 1947; Folder 612: Television Broadcasters Association 1947; NBC files, LOC.

105 Ibid.

106 "BAB Policy Group," Broadcasting, May 9, 1949, 25.

107 Ibid.

108 "Blueprint for a federated NAB," Sponsor, June 6, 1949, 28.

109 Ibid., 38.

110 Ibid., 36.

111 "Reorganize NAB?" Broadcasting, July 4, 1949, 23.

112 Justin Miller to J. M. McDonald, July 6, 1949; Folder 9: J. Miller, July 1949; Box 92; NAB Records; WHS.

113 "Meeting on July 21, 1949, Waldorf-Astoria, New York," memo, n.d.; Folder 9: Justin Miller-Television Department, 1945–1953; Box 112; NAB Records; WHS.

114 Ibid.

115 "Streamlined the NAB," Broadcasting, July 18, 1949, 23.

116 Ibid.

117 "NAB Revamping," Broadcasting, Aug. 1, 1949, 26.

118 "NAB's FM-TV Aims," Broadcasting, Sept. 12, 1949, 26.

119 Justin Miller to Clair McCollough, Aug. 29, 1949; Folder 9: Justin Miller-Television Department, 1945–1953; Box 112; NAB Records; WHS. At the same time, Justin Miller received word that ABC was looking to defect from the NAB.

120 "NAB's FM-TV Aims," 40.

121 Ibid.

122. Ibid., 26.

123 Justin Miller to Hugh B. Terry, June 20, 1949; Folder 8: J. Miller, June 1949; Box 92; NAB Records; WHS.

124 Mark Woods to Justin Miller, July 21, 1949; Folder 7: Justin Miller, American Broadcasting Company, 1946–1953; Box 96; NAB Records; WHS.

125 Justin Miller to the NAB Board of Directors, Feb. 24, 1950; Folder 14: J. Miller, Jan.–Feb. 1950; Box 92; NAB Records; WHS.

126 Eugene S. Thomas to Justin Miller, Feb. 27, 1950; Folder 4: J. Miller-Networks, the NAB Membership and Relations, 1945–1950 (hereafter Folder 4); Box 108; NAB Records; WHS; John F. Meagher to Justin Miller, Feb. 28, 1950; Folder 4; Box 108; NAB Records; WHS; Hugh B. Terry to Justin Miller, Feb. 28, 1950; Folder 4; Box 108; NAB Records; WHS; Gilmore N. Nunn to Justin Miller, Mar. 2, 1950; Folder 4; Box 108; NAB Records; WHS.

127 William B. Quarton to Justin Miller, Feb. 28, 1950; Folder 4; Box 108; NAB Records; WHS; Robert D. Swezey to Justin Miller, Mar. 3, 1950; Folder 4; Box 108; NAB Records; WHS; Charles C. Caley to Justin Miller, Mar. 10, 1950; Folder 4; Box 108; NAB Records; WHS.

128 Harry R. Spence to Justin Miller, Mar. 1, 1950; Folder 4; Box 108; NAB Records; WHS.

129 Justin Miller to William B. Quarton, May 4, 1950; Folder 4; Box 108; NAB Records; WHS.

130 "CBS Quits the NAB," Broadcasting, May 22, 1950, 23, 40.

131 "CBS Quits the NAB," 23; Justin Miller to John J. Gillin Jr., June 7, 1950; Folder 2: J. Miller, April–May 1950; Box 93; NAB Records; WHS.